|

| Michael Landy: Dragon fly (detail); courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery |

Michael Landy – the most popular destroyer in the West and member of the elite ‘Sensation Generation’ – launched a new show in December in the Thomas Dane Gallery in London’s Duke Street. Welcome to my world built with you in mind is effectively a spin-off of his controversial Tate Britain installation Semi-detached, which ran from May to December 2004. The theme and content are almost identical to the Tate exhibition, the main differences being that the works are now on sale and that there is no replication semi-detached house in this fun-sized gallery.

|

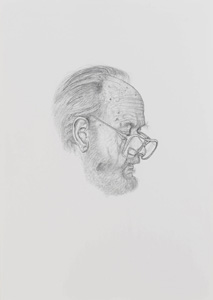

| Michael Landy: Dragon fly; courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery |

The works are divided into two groups, the father’s body and the father’s possessions, all reduced to the same format. Isolated items are reduced in size, drawn with pencil on paper and framed inconspicuously in cream or pastel. The works delve further into the artist’s current case study – the life of Mr. Landy Senior.

It would be interesting to view this exhibition without having prior knowledge of the artist’s father’s life, but that is impossible as now this story is as public as the artist himself. (He was injured in a mining accident at the age of thirty-seven, Landy’s age at the beginning of this project, and since then has been incapable of working and more or less isolated in his modest suburban semi-detached house.) Burdened with this background, it is impossible to isolate one’s viewing experience and approach the exhibition objectively. Landy uses this fact to his advantage; sensationalizing his father’s life, he breathes compassion into the viewers’ lungs. One has little chance of leaving the gallery unmoved, however reluctantly.

|

| Michael Landy: Daily Mirror; courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery |

The works in the exhibition are divided between the Duke Street Gallery and the Back Gallery. The Duke Street Gallery contains twelve drawings of various parts of the artist’s father’s body: his right ankle, his right hand holding a smoking cigarette, a side profile of his mature ‘working’ face – glasses balancing on nose, concentrated brow with head pointing down. Each drawing is isolated on the centre of the paper, scientific in layout, yet personal in approach. The drawings’ progress may be viewed through the development of colour: the first few drawings are simple and effective black-and-white studies of the old man’s delicate limbs. As the works develop the studies become those of identity rather than anatomy, and as Landy senior’s face and scarred limbs are revealed the artist begins to use colour. The colours – purple, pink, green, yellow and orange – are Landy’s means of engaging the viewer and prompting empathy. The twelfth and most stunning piece is that of his father’s inside left leg, with veins and wrinkles and a long fresh scar with immaculately rendered stitches. Landy’s skill as a draughtsman are clear and the work, although somewhat strengthened by the viewer’s prior knowledge, is impressive to say the least.

|

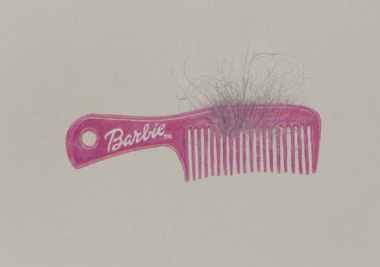

| Michael Landy: Barbie comb (detail); courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery |

The Back Gallery contains fifteen works, this time household items from Landy’s father’s home, all displayed in earthy pastel frames matching the paper they were created on. The colours of the paper and frames are sombre and soft, adding to the tone of sadness. The items are drawn in miniature, dwarfed by the size of the frame, Landy hinting at the tragedy of isolation. Each solitary item would be itself potentially insignificant- memos, phone numbers jotted down almost illegibly, a lighter, matching lighter fluid – were the audience ignorant of the tragic living situation of the artist’s father. Once the viewer is aware, these items represent far more. These are the daily objects that replace any daily events; these small works stand for far greater than the sum of their parts.

|

| Michael Landy: Barbie comb; courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery |

Landy is an artist, a draughtsman, a colourist, a soul troubled by the tragic fate of his father, but he is also an opportunist. His father can be seen as a figure used by Landy to promote himself, sensationalizing his father’s weaknesses rather than marking his strengths. Landy capitalizes on the public’s demand for tragedy and in doing so sells his work. In Breakdown the artist destroyed all of his worldly possessions, thereby making them public to the world. In this new chapter, he explores both the physical characteristics and personal possessions of his father, but has he gone too far?

I feel as a viewer both enthralled and saddened by the tale of Landy senior, and entranced by these illustrations by his son. However, one question remains – is this exploration into somebody else’s privacy art, or simply sensational voyeurism?

Isobel Harbison is currently a freelance art writer based in London.