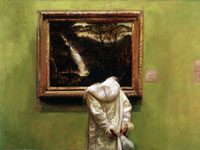

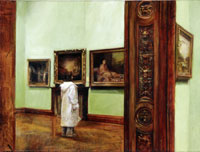

The walls in Margaret Corcoran’s paintings are green – the walls of the Milltown Rooms in the National Gallery of Ireland (which contain the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century paintings of the Irish School depicted in Corcoran’s canvases) are green too, but it’s not the same colour, and in that interval lies all the difference. Instead of a stately implacability, the green in Corcoran’s canvases (eight in the series) proves inconstant in its supposed task of providing a background. Ebbing at times to a thinned-out, pooling sepia, clinging to striations in the canvas weave (for example, in areas of An Enquiry IV ), fortified to a creamy lime (for example, near the top of the canvas in An Enquiry I ) Corcoran’s paint can also compress and contract itself in remarkable atoms of opacity. In one such example, a tiny, bimorphic dab – virtually embryo-shaped – in An Enquiry II, A Moment of Youth , is both formed by yet competes with the swirls of the painting’s ornate frame: the unruly organic interloper generated by the frame simultaneously escapes enclosure by it.

A Derridean attention to the notion of the parergon – to the disruptive potential of the frame, as that which is and isn’t the painted work (ergon), neither essential nor external to it – is invoked by this moment and others in the exhibition.And that it can be invoked by such a tiny locus within the series exemplifies Corcoran’s subtle but lavish ambition across its span. The Burkean text of the title could not represent a larger, more canonical respresentative of the Western tradition in its universalizing reach, its august categories – assumptions that are set quietly adrift in these paintings as surely as the softened but emphatic representations of paintings by Burke’s contemporaries deliquesce in the spaces of Corcoran’s canvases. These adumbrated paintings by Barrett, Roberts, Barry and others too – the serenely Orientalizing portrait of an Indian woman by Thomas Hickey or The Conjuror, Nathaniel Hone’s battlecry against Joshua Reynolds – hold and sometimes don’t hold the gaze of the young female figure who appears in every single painted scene as she walks through the rooms. This central device is a brilliant conceit that involves the viewer of Corcoran’s own canvases in a ramifying, self-reflexive sequence of delayed specularity. And it ensures that the by-now contested and proliferating literature on gendered spectatorship and the gaze (with even Laura Mulvey referring to it as a portmanteau of critical thinking on scopophilia) receives an acutely focused reading. Corcoran’s canvases return us, for example, to Erwin Straus’s seminal phenomenological differentiation between beholding – a thing of the body standing, walking, moving upright in space and time – and viewing as the disembodied ocular gaze.

|

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry IV, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry I, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry I, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry II, A moment of youth, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry II, A moment of youth, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist ; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

Margaret Corcoran: from An Enquiry, oil on linen, 2002, 46 x 61 cm; courtesy the artist; click on the image to see a larger version of it

|

|

|

| Such ambition marked Corcoran’s two previous exhibitions at the Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, the first entitled Companion Pieces (1999) and the second La Primavera (2001). In these exhibitions, suppressed and haunted voices in the representational language of French Salon painting were given forms alternatively searing and monumental (the truncated, severed bodies in Companion Pieces ), or mercurial: a site of jouissance, the stuff of beauty – the ribbons, petals and tears in La Primavera . In An Enquir y , Corcoran’s vision seems different. Not different in kind, however: that simultaneous conjuring yet evaporation of form that is Corcoran’s alone is as beautifully offered here as it was in the fragile interstices of La Primavera . (For example, the female viewer’s long white coat that appears in all the paintings in An Enquiry is not quite the radiant focus it promises to be: making a blurred fall to the floor in An Enquiry IV, in An Enquiry I, it trails off into a limp and delicate spray around wrists and hood – and in front of Barrett’s sublime cataract too). Different rather, in vision. If gentler than Companion Pieces, An Enquiry is also more ultimately generative of an affective space which appears at once melancholic and hopeful. An affective space, that is, comparable to the one created by Poussin in his second version of the Arcadian Shepherds (c.1646) where, as Louis Marin has so brilliantly argued, a supreme Parnassian reverie is chilled but held by the fugitive, desubjectivized Ego of the tomb. What, asked Marin, is the relation between language and painting if, in speaking of painting, we undermine the intense pleasure that is its end? As Marin asserts, Poussin’s achievement was – and this is what is echoed by the reach of Corcoran’s work – to proffer a constellation of elements that does not yield consummation or reprieve, but that holds and casts a spell at once unstable and enduring.

Dr Margaret MacNamidhe is a lecturer in the History of Art Dept in University College, Dublin.

Margaret Corcoran: An Enquiry, Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, September 2002 |