For me, sculpture is the body. My body is my sculpture.

These words, spoken by Louise Bourgeois, encapsulate the essence of the exhibition of her work, Stitches in Time , which is now showing at the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Rather than being a retrospective, the show consists of over twenty recent pieces and a number of works from the beginning of her career. This is the first solo show of Bourgeois’ work in Ireland and is housed in the new exhibition space at IMMA.

The juxtaposition of Bourgeois’ contemporary work with her older pieces is striking – the sculptures and etchings are shrewdly chosen and complement each other, serving to highlight the underlying themes that have continuously pervaded her work, while also marking the vast artistic and creative development that Bourgeois has undergone in her sixty-year-long career. For example, a series of engravings with text, He disappeared into complete silence dating from 1947, is contrasted with three contemporary totemic structures which loom over the viewer. These abstract, fabric-covered sculptures are a clever anecdote to the eerie scenes of suffering and loss related in the nine prints. Also, by reinterpreting a number of earlier bronze sculptures in stitched fabric, Bourgeois returns to her roots and to the tradition of tapestry she grew up with, coming as she does from a family which ran a tapestry restoration business.

When I was growing up, all the women in my house were using needles. I have always had a fascination with the needle, the magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness. 1

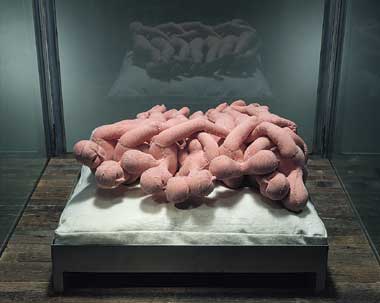

Frances Morris, senior curator at Tate Modern and co-curator of the show with Brenda McParland, chose the title Stitches in TIme because of these connections between Bourgeois’ roots and her later work: over the period of her artistic career and through a variety of different media, Bourgeois has developed a number of strands to her work which are ‘stitched’ together by one underlying and dominant theme, that of her childhood. 2 In particular, she uses the memory of her father’s open affair with their live-in English tutor3 as a springboard to examine issues of sexuality, unconsious desires and the body, as displayed in pieces such as Oedipus (2003) and Seven in a bed (2001), where childhood innocence, fairytale and nursery rhyme are reexamined in the light of adult knowledge and experience. However, while using autobiographical, personal memories as a source of inspiration, Bourgeois transcends the particular to achieve a universal art that involves the viewer in ways that is often disturbing, sometimes shocking, but never unsatisfactory.

Louise Bourgeois, Seven in a Bed, 2001, fabric, stainless steel, glass and wood, 172.7 x 85 x 87.6 cm, Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York, Photo: Christopher Burke |

Bourgeois has always been preoccopied with themes of childhood, sexuality, trauma and alienation. This exhibition displays her interest in the female body in particular – how it is constructed, dehumanised and objectifed. Bourgeois both forms and deforms the body, initiating a sense of estrangement through disturbing poses and missing limbs. Depersonalising her figures by not giving them the detail of a specific individual and by dismembering parts of the body, the focus becomes an examination of the construction and deconstruction of the body and the traditional depiction of the human figure in sculpture.

The style, medium and subject matter are inextricable for Bourgeois. Eschewing her earlier use of bronze as a medium, in these works she stitches together fabrics, evoking tapestries and patchwork crafts. By doing so she questions the conception of sculpture as a high art which utilises an expensive material and idealizes the body. The art of sewing, traditionally seen as a craft relegated to the woman’s sphere, is remade and revised in Bourgeois’ sculptures. She is not merely endowing the craft with a ‘high art’ status, but is remaking the very concept of what constitutes sculpture and ‘high art’, thus initiating a questioning of boundaries and a reformation of the traditional separation of art and craft into two distinct and tiered spheres.

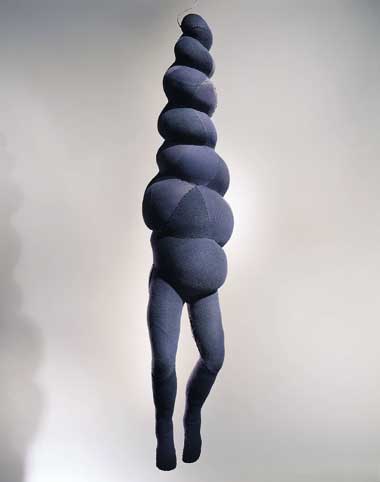

Louise Bourgeois, Spiral Woman, 2003, fabric, hanging piece, 175.2 x 35.5 x 34.2 cm., Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York |

In the first room of the exhibition, the viewer is confronted with Spiral Woman (2003), a fabric body hanging from a meathook. Instead of a head, arms or a torso, however, there is only a shell-like spiral shape, from which a pair of legs dangle. The black fabric and visible seams used in this piece conjur up images of female hosiery, and one thinks of the beautification of the female body by hanging it with clothing to create an exterior image that can ensnare, objectify and deny any sense of individuality. In the same room is Femme Maison (2001), which deals with another aspect of the female position. A stuffed female torso without a head, legs or arms and thus reminisecent of broken classical statues, lies on its back and is covered in fleshcovered patchwork. Emerging from its stomach is the simple shape of a house, sitting on top of the body as though on the crown of a hill. The female body becomes a landscape onto which meaning is inscribed, with the piece being a witty and very literal representation of the French title. It refers to the woman’s traditional position as a housewife, and to the more positive concept that it is the female of the house who gives it its stability and strength, while also, through the medium, paying homage to the ‘domestic’ art of patchwork.

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 2001, fabric and steel, 35.5 x 38.1 x 66 cm, Courtesy Galerie Karsten Greve, Koln, Paris, Milano, St Moritz. Photo: Christopher Burke |

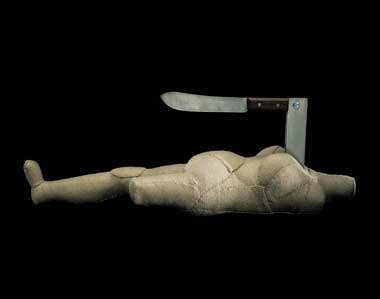

In a different room is another, more disturbing stuffed fabric woman. Femme Couteau, 2002, is again a female body in fleshpink fabric with a number of limbs missing, but in this work the figure evokes a stronger sense of dismemberment. Without a head or arms, the body has one leg, thus highlighting the absence of the other leg. Poised above the body on a metal bracket is a large butcher’s knife, which gives a distinctly menacing and violent aspect to the work, as though a woman is only a sum of the parts of her body, a mere hunk of meat.

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Couteau, 2002, fabric, steel and woood, 22.8 x 69.8 x 15.2 cm, Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York, and Galerie Hauser and Wirth, Zurich, Photo: Christopher Burke |

A number of works in this exhibition are housed in glass vitrines – Cells – that separate the work from the viewer and trap the displayed heads and figures within. Cells are the most basic building blocks of life, but the word ‘cell’ can also mean a prison, it can be a form of entrapment. For Bourgeois, these cells represent “different types of pain: the physical. the emotional and the psychological, and the mental and the intellectual."4

Arched figure, 1999, is enclosed in such a glass case. Hanging suspended and in pain, the armless figure arches her back to get a view of her face screaming in a freestanding circular mirror. In a dislocating experience, we see the agonised face in the mirror first, through the looking-glass. Because of the awkward pose, the viewer has to walk around the glass cell in order to get a proper look at the screaming face. The very particular placing of this figure and the presence of the glass that encases it means that we experience this work through glimpses and by shifts in perspective as we approach it and move around it.

Louise Bourgeois, Arched Figure, 1999, pink fabric, mirror, wood and glass, 190.5 x 152.4 x 99cm, Courtesy Private Collection, London, Photo: Peter Bellamy |

In contrast with this work, at the other end of the room are two untitiled works from 1996, one being a freestanding mobile. Integrating with the room, this work uses a number of female garments that were salvaged from Bourgeois’ childhood home, draping them on large bones which hang from meathooks. As curator Morris explains, this is a “meditation on mortality. The cloth fragments represent the human figure, the exterior, what we put on; the bones are what is underneath."5 In the same room are a series of nine copperplate etchings, entltled topiary, the art of improving nature (1998), in which trees morph into bodies, and images of crutches and missing limbs draw parallels between dismemberment and the ‘improvement’ of the body.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1996, cloth, bone, rubber and steel, 300.3 x 208.2 x 195.5 cm, Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York, Photo: Allan Finkelman |

Some of Bourgeois’ most powerful works in this exhibition are her fabric busts, also housed in cells. The life-size heads do not have any individuality, they are trapped by the cases in which they are placed and the fabric materials used give the ghostly hint of features. A powerful reinterpretation of classical busts, these works show nothing of the composure depicted in marble representations of famous figures, rather the effect is to give an impression of the inner recesses of the mind, and the pain, doubt and humanity of existence.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2002, tapestry and aluminium, 43.1 x 30.4 x 30.4 cm, Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York, Photo Christopher Burke |

Bourgeois cannot be categorised into one particular style of twentieth-century art and, even though she analyses the experience of being a woman and uses sexuality as a theme, she does not fit the label of a ‘feminist’ artist and would never identify herself as such. The first female artist to have a retrospective at MoMA in New York, she is highly individual and relentlesly creative. Considering that Bourgeois is now 92 years old, the contemporaniety of the works on display is evidence that her creative powers remain as innovative and exciting as ever, and this exhibiton is testimony to the fact that Bourgeois is one of the most significant figures of twentieth-, and now twenty-first-century art.

1 Quoted by Cristin Leech, Art getting to the point, The Sunday Times, Dec 21 2003

2 Morris, in an interview with Amy Redmond, Stitching the threads of the past, The Irish Times, Sat Nov 29 2003

3 “In a piece commissioned for the magazine Artforum in 1982 Bourgeois combined a number of faded photographic images from her childhood with a revelatory text entitled Child Abuse.(6) Here she took the reader beyond the facade of comfortable gentility to a personal drama of betrayal and transgression. In 1922 the family hired a young English woman, Sadie, as governess for the children. As Bourgeois recalled: `she was introduced into the family as a teacher but she slept with my Father and she stayed for ten years. Now you will ask me, how is it that in a middle-class family a mistress was a standard piece of furniture? Well, the reason is that my mother tolerated it and that is the mystery. Why did she? So what role do I play in this game? I am a pawn. Sadie is supposed to be there as my teacher and actually you, mother, are using me to keep track of your husband. This is child abuse. Because Sadie, if you don’ t mind, was mine. She was engaged to teach me English. I thought she was going to like me. Instead of which she betrayed me. I was betrayed not only by my father, damn it, but by her too. It was a double betrayal. There are rules of the game. You cannot have people breaking them right and left. In a family a minimum of conformity is expected." Source: nyartsmagazine.com/louisebourgeois.html .

4 Bourgeois, quoted n art in the 21st century, www.pbs.org

5 Morris, in an interview with Amy Redmond, Stitching the threads of the past, The Irish Times, Sat Nov 29 2003

Eimear McKeith is a writer and critic currently based in Dublin.

Louise Bourgeois, Stitches in Time , Irish Museum of Modern Art, 26 November 2003 to 22 February 2004