The laboratory and the studio have a shared origin within the guild system, as the site of what were essentially craft practices. Across medieval Europe physicians, apothecaries and painters, all working with similar raw materials, united together in the guilds of St Luke. While these spaces and the tasks performed within them were dominated by men working in their professional capacity, they were similar to those in the kitchen, dominated by women working within the domestic sphere. This commonality in action and gesture underlying the practices of the hospital, laboratory, kitchen and studio form a core element in the work of Dublin artist Lucia Barnes.

At the same time, there is clearly a tension here, between the “familiar charm of the domestic" and the “seemingly relentless scrutiny of clinical, scientific investigation." [1] This tension led Wilhelm Dilthey in the late nineteenth century to stress the difference between the natural and the human sciences, in which the former seeks explanation based on the development of models, while the latter seeks understanding through the use of metaphor. The key question dividing them is the nature of the investigation, yet the split only began in the seventeenth century due to the invention of the experimental method and Francis Bacon’s stress on inductive reasoning. One of the historical ironies of this ‘two cultures’ theory is that experimentation is now central to art practice.

Barnes is in an ideal situation from which to explore the similarities of the ‘two cultures’, having had a previous career working in hospitals as a nurse as well as being involved in several arts-in-health projects. Her recent body of work, Synchronization, shown in the Ballina Arts Centre in May, was drawn from many of these sources and in particular was influenced by her time spent as Artist in Residence at the laboratory of St James Hospital.

While ‘synchronization’ obviously refers to time, it is a term also used in discussing complexity, interconnectivity, self-reflexivity and the self-referential, all themes which occur in Barnes’s work. Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, based on the sentence ‘This statement is unprovable’, demonstrates that in a self-referential system it is impossible to decide whether every element in that system can be proved true or false. In this sense, the self-referential is what gives rise to subjectivity. Israel Rosenfield argues that subjectivity implies the incompleteness of knowledge – which is the key driver in the search for scientific objectivity. Thus, based on our own subjectivity, we create a framework of universal ‘objective ideas’ – abstract concepts we all agree on, which we call ‘science’. [2] What Barnes does is to take the physical actions that take place in the laboratory, the kitchen and the operating theatre, and explore their simultaneous subjectivity and anonymity, the loss of identity in the specimens and samples that still remain attached to their very specific origins. Along the way serious questions are raised about the nature of knowledge and decision-making, about change, complexity and mortality, the undecidability of the image and the ritualised nature of many of our actions.

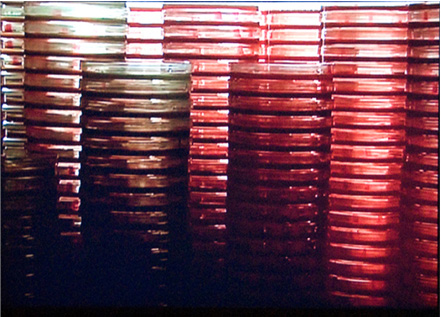

Her work is intentionally immersive, as she cumulatively builds piece by piece to articulate her themes. In the DVD No. 0287 trays of cultures ‘wait patiently’ to be processed, emphasising the regimented, automated nature of much mechanised medicine. Samples taken from individual patients become part of a homogenous assembly line, where the culture is added in a closed box, making the process invisible to the observer. This slippage between privacy and anonymity is echoed by the mechanically repetitive nature of the process, and the looping of the DVD further underlines this. In Metamorphosis, an installation of red moulded gelatine sculptures, the loss of identity happens through a natural process of decay over time. Clearly identifiable shapes begin to bubble, turning into puddles and losing their identity as they melt together. Although this is happening naturally, it is ‘anti-evolutionary’ in that the movement appears to be from complex to simple, rather than simple to complex. It is in any case unclear what these objects are: are they samples in a medical lab or condiment jars for sale in a kitchen shop?

Moving still takes this process of natural decay a step further. We see a teapot, dough wrapped in clingfilm and an oil jar, three glossy objects arranged on a dark ground reminiscent of a Dutch genre still life. Gradually, as the dough rises, a weakness is exposed in a seemingly perfect shape. The sudden collapse comes unpredictably, showing the apparently random process of change. Thus with time, the ‘still life’ becomes mobile, and the question arises of when the cork will pop off the oil jar or the varnish flake off the teapot. In this way the convention of the image is exposed, revealing “a point of undecidability in its functioning" [3] – is this a metaphorical restatement of a Dutch genre-style momento mori, or is it a kind of ‘naked image’ documenting a scientific process? This would reflect the practice of ‘demonstrative knowledge’, whereby the laboratory has become a ‘theatre of proof’, the place where knowledge is demonstrated, just like a museum or TV chef’s kitchen. The title of the piece leads us into another area of undecidability, the issue of apparent motion, where a succession of still presences yields an apparent motion – where perhaps there is no motion at all. [4] In film, the motion is subjective, as in reality there is only a succession of stills. However, like scientific concepts, the subjectivity of the ‘motion’ pushes us towards an agreed, ‘objective’ view of the world. In this way we can view the images symbolically as a ‘still life’, in synchronic time, while the motion is diachronic – an evolutionary succession of stills.

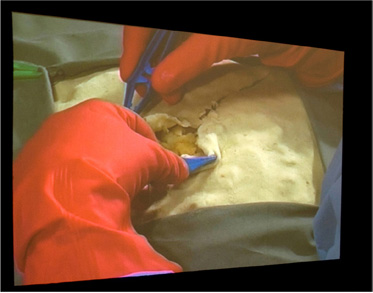

Perhaps the most immediately accessible and engaging piece, Evaluation, an 8.5-minute-long DVD, bridges the gap of art, science and domesticity most effectively, as Barnes performs a biopsy on an apple pie. At once gentle, funny and disgusting, it provides a sharp yet complex and subtle critique of the division of labour, alienation and over-specialisation in contemporary society. The piece is set in an anonymous workspace, part hospital ward, part operating theatre, part kitchen, complete with flowers, as well as an array of tools on the table ranging from surgical instruments and knives and forks to a child’s plastic tweezers from a science kit. It also reintroduces the teapot, oil jar and dough from Moving still. As the apples are carefully peeled, their stalks removed and they are chopped up, they are transformed from being individual, very identifiable, different ‘apples’, into an undifferentiated mass of ‘apple’, losing their identity in the process. The detritus is examined and discarded, and a sample – from any part of any apple – is taken. Suddenly we realise that all the pieces are coming together, as the dough is purposefully manipulated, and the elements are combined in the making of a pie. Thus a new form of complexity emerges, through the processes of taking apart and putting together. Undecidability happens when suddenly the pie becomes ‘human’ – you cannot but flinch as the line is drawn on the ‘skin’, the incision made and the flaps folded back. The ‘operation’ begins with a knife and fork, but quickly slips to using a scalpel, going into a surgical mode. The sampling of the cooked pie is dogged and difficult work, and after a bit of core has been extracted it becomes increasingly gory, the hands rooting, replacing ‘organs’, closing the ‘wound’ and mopping the stitches. The boundaries of our perception slip, as the conceptual beliefs about surgery take over from the simple perception that this is ‘just’ an apple pie.

The key difference here is the return of human agency, although in a most alienated form. The surgeon / cook is wearing kitchen gloves, a surgical gown and mask, and both the hair and eyes are protected. All the movements are careful and deliberate, clearly ritualised, prescribed and choreographed actions, such as examining and cleaning an already clean bowl, and carefully assessing each apple in turn. This immediately raises questions about the decision-making process – what is being assessed here, and what are the criteria for assessment? How will you know when you have found whatever it is you are looking for? This issue of the forms of knowledge, the aesthetics of knowing, is extremely topical at a time when the distinction between knowledge and information is increasingly blurred. While much has been written about the formal elements in discourses and disciplines, Barnes’s linking of the actions and gestures of disciplinary institutions to the ‘subjugated knowledge’ of the domestic sphere breaks the usual distinction of the domestic, the private, as being Other to ‘scientific’ scrutiny and dissection. The apple in the pie comes to reflect individual subjectivity, the undecidability and fluidity of identity and our vulnerability in the face of those who wish to explain us.

John Mulloy lectures in Art History and Critical Theory at the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology. July 2009