This article has just appeared in Art Monthly Australia #215 November 2008; reproduced with permission.

Out of the corner of my eye I catch the TV where CNN informs me that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose writings exposed the Gulag system in the Soviet Union, has died. I switch channels to the Beijing Olympics as they cross from the Water Cube to a medal ceremony. The golden Nike ‘swoosh’ fits into a unified design opposite the Chinese flag as the medals are hung around their necks. Is this the beginning of the ‘end of history’? I switch back to CNN.

Earlier I had arrived at my hotel just in time to drop my bags and get to a local restaurant to watch Beijing’s Opening Ceremony whose slogan reads One World One Dream, which strangely parallels my travel reading, The end of history by Francis Fukuyama. This book sets forth the idea that ‘[a]t the end of history, there are no serious ideological competitors left to liberal democracy’. [1] It is not an end to events as the title might suggest but an end to the evolutionary process that has developed the most rational form of government. Fukuyama believes this is liberal democracy in tandem with a market economy.

The ‘end of history’ logic prescribes that the accumulation of science and technology precludes a random or ‘cyclical history’ and instead insists upon a directional history. This Marxist concept was derived from the Christian belief that there was a ‘beginning’ followed by an end to history in the kingdom of God. Marxists believed that communism would form the political process at the ‘end of history’. However Fukuyama’s thesis concluded that the train stopped one station earlier and that liberal democracy, not communism, was the terminus.

I am in the Ramada Pearl hotel, in Communist China, Room 809 to be exact. I am here to participate in the Guangzhou Triennial hosted by the Guangdong Museum of Art. My room is both my home and a studio for a month. From here I will make my work and write my thoughts with a view over the river Pearl and the city, dominated by a futuristic communications tower still under construction. It looks something akin to a giant launch pad with the concrete fretwork forming a cocoon to some mysterious rocket.

Whilst reading and making my sculpture in room 809, I learn that before 1776 there was not a single liberal democracy on this planet, yet the concept has spread like a virus around the globe, replacing the autocracies, oligarchies, monarchies, and dictatorships, and is inexorably moving us beyond the post-colonial. The tipping point, when liberal democracy is demanded, is, according to Fukuyama, US$6000 per capita income, [2] provided by the mandatory market economy. He also argues that you can’t have good government unless accountability feedback loops are built back into the system.

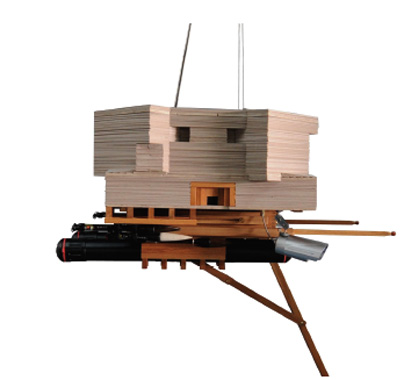

If I accept the ‘end of history’ theory as valid, and it is convincing, I believe my hotel room and studio becomes something like Douglas Adams’s The restaurant at the end of the universe. That is, from room 809 of the Ramada Pearl, I can look back at the Western world and into the future. This could be very useful as Adams’s main character, Arthur Dent, realised when told how to pay for his exorbitant restaurant meal: ‘All you have to do is deposit one penny in a savings account in your own era, and when you arrive at the End of Time the operation of compound interest means that the fabulous cost of your meal has been paid for.’ [3] As I work and ponder, CNN informs me that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac [4] look like they are in serious financial trouble that threatens to destabilise America’s financial markets. It seems Fannie and Freddie have been lending a lot of money on mortgages based on the idea that people who can’t afford it, will pay it back on some future date! Luckily this does not affect Arthur who continually jumps back into the past to survive the exploding universe and where he can book his table in retrospect. I on the other hand order late-night room service for Cliff and I as we work into the night. [5]

In Beijing, the fireworks explode in the stunning Closing Ceremony as I continue to puzzle over the Olympic slogan. What could a unified world of dreams mean? One world based on consumerism driven by the natural sciences and technological innovations that we are all experiencing? Fukuyama explains a market economy does not necessarily need liberal democracy and paradoxically, a communist state like China, with a market economy, can capitalise on an autocratic power structure, for without opposition it can be far more efficient in controlling demand. However technological consumerism eventually undermines such an authoritarian regime because the dissemination of information and its power become harder to control, and as wealth increases so does the desire for political recognition. China as a classic ‘post-modern’ society is built on irony. The contradictions are obvious but you never acknowledge or criticise openly for fear of undermining the change that is occurring within the monolithic structure.

As Solzhenitsyn’s funeral plays out in my memory, I come to understand the importance of the theory of‘recognition’ as put forward by Fukuyama. Especially when I contrast Solzhenitsyn with Edward Alexander Pilgrim. [6] Pilgrim is a name not nearly as recognised as Solzhenitsyn for he did not survive his collision with government. Pilgrim, a milkman, hanged himself in 1954 after a protracted battle with his council over land rights. He would be forgotten today except a law in the UK is named after him and Adams uses details of Pilgrim’s life as the catalyst for Arthur Dent’s journey through the galaxy.

Pilgrim’s experience reminds me of why it is important to contribute feedback into the system. I am inspired to contact the ‘Australia Council for the Arts’ through their Visual Arts Board (VAB). I am interested to see if they have improved their assistance to artists working internationally, since I last wrote [see Letters in AMA September 2008, #213], but am left disappointed. [7]

The Guangzhou Triennial with its curatorial premise‘Farewell to Post-Colonialism’ would seem to engage with Fukuyama’s thesis not only on a broader political level but also based on the technology revolution that is globally progressing and promising a directional art history. The concept statement of the Triennial includes: ‘In the age of hyper-reality and Internet existence, when we can readily access alternative realities and other live-worlds through virtual technology, what does ‘art practice’ implicate?’ [8] Maybe a journey like that undertaken by Adams’s character Zarniwoop who in 1978 went ‘ … on an intergalactic cruise in his office via his virtual universe’. [9]

As my CNN days roll on and the work nears completion I become entranced by the American Democratic National Convention (DNC), only stopping to go online to read about it. I come across A.A. Gill in The Times who is in America observing not only the DNC but also his fellow journalists: ‘ … I can’t help noticing that one of them spends most of his time chatting on Second Life (a name that implies a lack of a primary one). His avatar is seven sizes thinner than he is.’ [10]

There is no doubt that the evidence suggests that technological innovation is driving art and I accept it is becoming an increasing directional progression. But does new technology equal creativity, or are we, like the journo, deluding ourselves? Unlike older more difficult mediums technology democratises the ability to create images at will. If he was alive today Clement Greenberg might well have successfully applied his modernist theories to contemporary technology and new media for they would seem to suit the term ‘medium specificity’, which means that ‘the unique and proper area of competence’ for a form of art corresponds with the ability of an artist to manipulate those features that are ‘unique to the nature of a particular medium’. [11] By the time art got to ‘Cultureburg’, [12] Tom Wolfe argued that visual arts had been reduced to a banal literature. Greenberg along with his theories have long been assigned to Cold War history, however we must acknowledge that he did identify the danger of when ‘Art’ enters the ‘maw’ of capitalism and how it can quickly become propaganda or even entertainment.

The end of history determines that post-Cold War, liberal democracies (Fukuyama compares them to billiard balls on a table) are less likely to come into conflict with each other on his metaphorical ‘super fl at’ landscape, due to their preoccupation with the market economy. From this we might suspect that there will not be an abrasive ‘end of history’ and art will no longer grow out of creative opposition. No future Fluxus or Dada movements but slick art (utilising slick technology) assisting the art bureaucracy into forming a global art market. For at the heart of liberal democracy is the dream of a global market, and its core function is to increase efficiency to drive productivity to drive the economy that gets everybody $6K a year to drive for liberal democracy and the ‘end of history’. The art‘industry’ is now intertwined in this process. ‘Creativity = capital’ as Marx supposedly said. [13]

Market economies by their nature reduce complexity into easily consumable information. For example, they can take 100 diverse companies and reduce that incredible complexity down to a simple index that either goes up or down each day. It does the same with art with some encouragement by the art bureaucracy. The example of the Australia Council for the arts shows us even an organisation set up to support the arts values efficiency over art. Their philosophy is one of the bus-driver who believes he can be far more efficient if he doesn’t pick up any passengers, an internal ‘virtual’ logic that eradicates meaning in the real world.

Counteracting this drive for efficiency and simplification is the Triennial’s most important message; ‘multiplicity’ of social existence is no longer limited to the cultural diversity of different kinds of social ‘tribes’, but also points to the multiple life-worlds and existential fields that are present in every single individual. Today, ‘alien existence’ is not simply about living among ‘the Other’, but is equally about ‘diverse existence’ found within every corporeal being. [14] As Bill Clinton might have said: ‘It’s the complexity, stupid!’

My work leaves Room 809 and is taken to the Museum which leaves me time to watch more of CNN’s coverage of the DNC. Coincidentally Barack Obama’s speech coincides with the 45th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech. It was a very simple and human dream: ‘I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.’ [15] CNN shows an old black man crying as the reality of Obama’s nomination sinks in. In the hotel I pick up the Pearl River Delta magazine, which has as its cover story ‘City of Dreams – Shenzen from village to megacity in 30 years’. One World – One Dream?

The day after the exhibition I arrive, hung over, at the airport where the clothes shop sign reads ‘Sale 50% up’! I am still smiling as I enter the restaurant at the end of the terminal. I watch a TV showing a Chinese version of‘funniest home videos’.

Landing at Heathrow Airport at 5.05am, I proceed on my way to the small Irish departure terminal. I am the first passenger through Flight Connections. At the terminal I collapse in front of a monitor where the BBC informs me that Damian Hirst, looking more and more like Bono, has put his latest collection of work straight into auction at Sotheby’s. After all I have learnt on this trip I understand what he is doing. It makes perfect sense. He is making his business, which is art, more efficient because he is cutting out the art bureaucracy, the critics, the galleries, the curators and the dealers. It allows only one value to be put on the work and one adjudicator – a monetary value placed there by the market. Hirst is reported to have said that an auction is ‘a very democratic way to sell art’.16 We have reached the end of history!

Postscript: On the night of the sale, ‘Mr Hirst spent the evening playing snooker, but on being told the sale figures, he pronounced: “I think the market is bigger than anyone knows”.’

John Kelly is an Australian, British and Irish artist living in Cork. He was invited to participate in the Guangzhou Triennial as a ‘Free Radical’ and was supported by Culture Ireland.