“Utopia means nowhere or no-place. It is often taken to mean good place, through confusion of its first syllable with the Greek eu as in euphemism or euology. As a result of this mix-up, another word dystopia has been invented, to mean bad place. But, strictly speaking, imaginary good places and imaginary bad places are all utopias, or nowheres. " [1]

In search of Utopia was a recent group exhibition featuring Dorothy Cross, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Louise Manifold, Michelle Browne, Cao Fei and Dennis del Favero, curated by Maeve Mulrennan in the Nuns Island Theatre of Galway Arts Centre from 23 May to 6 June 2009. Coinciding with the Volvo Ocean Race, the exhibition took as its starting point the motion of the race itself. “It can be seen as a metaphor for how we are constantly searching for something better, always moving towards what we see as a preferable situation to what we are currently in.” [2]

The exhibition title was a suitable one for the contents of the exhibition, in that it made no allusion to an actual utopian discovery. Rather, it acted as an invitation to accompany the artists on their specific voyages of discovery and revelation. The curator and theatre designer Tony Cording together laid out the exhibition space. Imaginatively constructed as a subterranean cavern, the interior of the theatre became a blacked-out space containing various chambers with the artworks installed inside. Each chamber held a different possibility and thus acted as a natural lure for the viewer. This cocooning of the artworks heightened the sense of drama as one walked around the exhibition space.

There is a sinister undertone in Ailbhe Ní Bhriain’s work. Her projected video, The Suspension room (1), seems to relate to a stage set or an empty studio lot on a film production, introducing layers of special effects that overlap and disjoint perceptions of time and space. Accompanied by an eerie piano melody, an animal carcass appears abandoned, yet carefully positioned in the foreground of her slowly unfolding composition. These gestures reflect a brooding and pensive mood. There is a sense of speculation: a look towards the end of the future? The death of the modern?

Dorothy Cross showed two video works, both reflecting on a meditative state of mind. In Ossicle, a whale bone is pushed by the artist’s hand to create motion; the bone now becomes a pendulum. In Selam shark-caller, Cross has focused on a Melanesian tribe from New Ireland in the Pacific Ocean. The camera records an old man trying, with obvious emotion, to remember the words of a song. The narrative here seems to be wistful in relation to culture and a natural setting on the cusp of disappearing, with the videos’ central characters and objects being all too aware of this.

Louise Manifold exhibited new works developed from her ongoing research into Fata Morgana, an optical phenomenon or mirage where far-distant objects or shapes can appear to float on the horizon. In one alcove of Nuns Island, Black carousel was contained in a belljar. Made from paper and reflecting ships and prehistoric seamonsters from myth and imagination, the carousel revolved and projected these images onto the walls of the space. Bird boat (a representative sculpture: part bird, part boat) was hidden behind a mirror in the same space, where the discovery of this piece seemed left to chance. A third artwork by Manifold was located outside the building: an installation of mirror glass onto the existing windows featured Manifold’s drawings of bird-like creatures.

Todtnauberg, a video work by Dennis Del Favero, investigates events surrounding an encounter between Jewish poet Paul Celan and the German philosopher Martin Heidegger in 1967. They met to discuss issues relating to World War II that they hoped to resolve. Del Favero’s project concerns itself with the silences and amnesia that haunted both the encounter and the events surrounding it. Using actors to play the part of Celan and Heidegger, the film is shot in black and white and filmed in a maze. Found footage of old newsreels is interspersed into the video, as sleek pans of murky undergrowth come together with Nazi marches and Aryan children. A culmination of almost silent intonations of the conversation with a mesmeric camera sequence creates an altogether intense and claustrophobic piece of art. This is further emphasized in the installation: the work is displayed on a small flat-screen with headphones. The need for the viewer to stand especially close to the screen, due to the length of the headphone lead, further immerses the viewer.

Cao Fei’s video piece, Whose Utopia?, looks at workers in the Osram Lightbulb factory in the city of Guangzhou, China. Her camera records the lives of emigrant factory workers and how their status has changed in the overwhelming trend of globalisation. Beginning in the factory itself, the documentation of machinery and components to create the standard lightbulb becomes a captivating movement of the camera. A narrative then unfolds into small moments of personal mini-Utopias within the factory itself; a dancer appears in a storeroom, a worker plays electric guitar on the factory floor.

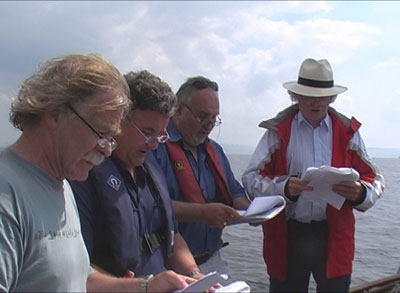

A Life on the ocean wave, a site-specific performance by Michelle Browne, took place off Salthill on 30 May. Inspired by Bas Jan Ader’s fatal attempt to cross the Atlantic single-handed, a choir sited on a Galway Hooker sang A Life on the ocean wave by Henry Russell, the sea shanty played at the launch of Ader’s expedition in 1975. The sound was streamed back to shore and played on loudspeakers to the people gathered on the beach, creating an uncanny interaction between boat and shore. On the day, people used binoculars to view the choir in the distance and often attempted communication by shouting out to the boat.

Many divergent tangents around the Utopia theme were explored at length in Nuns Island. Though ‘Utopias’ ‘strictly speaking’ mean nowhere, the Utopias in this exhibition could be read as being relevant everywhere.

Michele Horrigan is an artist and curator of Askeaton Contemporary Arts.