According to the curators of this exhibition, their starting point was a conversation about the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s search for solitude in the wilds of Ireland and Norway. Wittgenstein was indeed a peculiar figure, not least in the contradiction between his residual misanthropy and related quest for solitude and his thorough philosophical dismantling of the notion of ‘private language’. For Wittgenstein, what is thought of as the ‘natural non-social me’ is a social convention, and the signs that this ‘me’ makes use of are without meaning outside of those already ‘in play’ in a social milieu: it is only from the heterogeneity of social meanings that the meaning of the subject ‘I’ can emerge at all. That Wittgenstein retreated into isolation so that he could show such isolation (in language at least) to be illusory presents us with a paradox: one that forms an appropriate background to this whole exhibition, although there are, of course, some unusual diversions throughout.

|

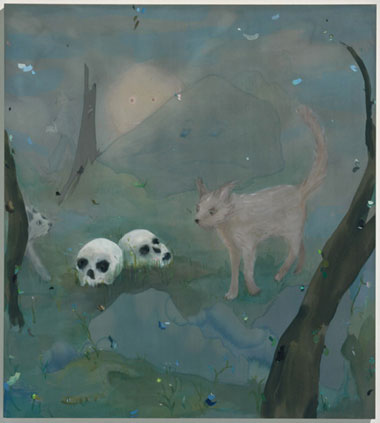

| Laura Owens: Untitled, 2003, oil and acrylic on canvas, 165 x 147 cm; courtesy Douglas Hyde Gallery |

Laura Owens’ Untitled shows two cats sniffing around two skulls, which return their gaze. The surrounding, fantastic landscape is animated; the hills and sun having imbecilic, cartoon eyes. The whole painting is, in fact, imbecilic: a saccharine fantasy that erases darkness and shadow from the scene by its use of pastel-shaded stains of paint. The scene is desexualised (note the asexual ‘human’ figure carrying some porcelain object). Perhaps, though, by passing to such sweet extremes, the scene becomes nightmarish, or disconcerting at least. Is such painting the result of daydreams had in isolation? Or, more precisely, the therapeutic counter-fantasies of a teenage girl vaguely disturbed by the encroachment of adult sexuality? The ‘hut’ here seems to be the teenage bedroom: a den of impenetrable sentimentality; a psychological domain, uncertain and vague but stubbornly asserted – the process of adolescence is a necessary retreat from which many never return. On a less fanciful level, it seems a shame that when requested to submit a painting for a show with a specific theme, Owens has submitted a work that makes no departure from her signature style, when style itself is an all-too-common ‘hut’ for artists.

The Single family house by Verne Dawson sits detached against a pallid blue ground that could be a sky or a stretch of water. In cross-section, all the rooms are open to view, each one characterised by a colour, a landscape or a thick wash of paint: red, black, river, copse, snow, two figures face one another in a dark room. Memories of domestic events are coloured, and they stain the surrounding room, obliterating details. Here we have a ‘hut’ that is architectural, but also plays out the psychodrama of a rather complicated social configuration, the family, seen from the point of view of those involved in the family perhaps, rather than from the ‘sociological’ perspective of quantifiable behaviour and patient observance that is repeated in the position of artist-viewer-observer. So, the house on a hill, or at the end of a promontory, tightly enclosed about itself, isolated; a place of claustrophobia, degeneration and misadventure – a metaphor for the individual psyche, the psyche as family house … but does this painting, like Owens’, function as emotional therapy, and as false reconciliation with a family’s solipsistic tendencies? Perhaps there is a narrative here concerning the emotional vulnerability and complexity of the family unit and those ‘subjected’ within it: a narrative that stresses the ‘tyranny of intimacy’ (Richard Sennett) in our psychology-obsessed culture.

One could always leave the family altogether and get ‘back to nature’. Daniel Richter’s portrait of Tal R shows a bearded man with white eyes, tie-dyed t-shirt and trousers, prostrate, levelled in contemplation of a dead songbird, mirroring its mortified posture: the artist here as hermetic poet, beatnik songster, ‘man of the woods’, not to be taken too seriously. But is the hermit still alive? Is his position of ‘stillness’ and of "’lived’ innocence and warmth" (press release) in fact rigor mortis? Richter’s other painting, Untitled, shows a female figure in a similar position to the songbird, this time gazing up through stormy treetops, surrounded by debris. Again, what could be contemplation and reverie could also be death, suggesting even that artistic creation might arrive via a kind of ‘death’. One is reminded of well-known saying that ‘art is borne of boredom’: the ennui of being alone, having nothing to do but gaze at the trees or the corpse of a bird … art being a means, then, of ‘resurrection’ for some; of just passing the time for others.

|

| Avner Ben Gal: Corn, 2004, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 95 cm; courtesy Douglas Hyde Gallery |

Avner Ben Gal also makes use of a hermit. In her Corn, we are shown a crazed black man – conforming somewhat to type; large balls hanging, skinny body, ‘afro’ hair and beard – tending to his harvest of scorched corncobs in front of his equally scorched and dilapidated shack. The place is a mess, strewn with eroticised detritus. Like a parody of Saint Anthony in the desert beset by self-imposed temptations to test his faith, nightmarish visions that densely populate his arid environment and in a perverse way keep him company, the hermit here transforms his own parched crop into symbols of the most gleefully paraded sexuality. However, his ‘madness’ might well be the result of dispossession, and it is further fed by the anxiety of those in possession of goods and land concerning the ‘unpredictable’ actions of those living in destitution. Ben Gal’s other painting, The eve of destruction, follows all too literally the hackneyed association of violence and madness with strangers in dark alleys.

Chris Ofilli uses the story of Odysseus’ detainment by the nymph Calypso to suggest other ‘huts’; the lure of reconciliation over and against struggle, or more precisely, the lure of eternal libidinal satisfaction in uneasy correspondence with the command ‘cherchez la femme!’. For seven years, Calypso attempted to seduce Odysseus and keep him on the island of Ogygia. Although Calypso eventually abandons her attempts and assists Odysseus to complete his return to Ithaca, Ofilli’s painting shows one of the moments when Calypso – coyly eating from a bunch of grapes, all curves and vaginal folds, as sexually aggressive as Matisse’s Blue nude – tempts Odysseus with the promise of supernatural passion. The scene is enchanted by the silvery light of the moon, shining from the eyes of the two characters – a voluptuous, seductive and sickening light. A charmed cobra stands erect, its poise reflecting (and threatening) that of Odysseus at the moment of decision: does he accept eternal confinement (and immediate sexual gratification, itself a petit mort ) on Calypso’s island or continue to "stray grievously about the coasts of men É to redeem himself and bring his company safe home’" (Homer’s Odyssey )? Is he to chercher la femme in the figure of Calypso or Penelope? Odysseus’ choice of the latter is perhaps a choice already made elsewhere, but Ofilli, by bringing us back to the decision that begins the Odyssey, re-opens this fundamental choice … and making this decision has never been more pertinent, not least in the highly sexualised consumer environment.

Michael Raedecker’s diptych Independence reads, at the first approach, like a ‘spot the difference’ puzzle. Indeed, the squared floor suggests the playing of some obscure game – a play on difference and repetition, and, of course, a play on independence and dependence. The two paintings copy each other, with only the slight discrepancies that one would expect of hand-painted reproductions. A peculiar symbolism seems to be at play within an insubstantial but enclosed architectural space: bottles as containers for thoughts, perhaps, or figurines to be manoeuvred about a board; a white glove, a gauntlet lain down; an abstract passage of paint on the right of each painting emphasising the difference in ‘frequency’ between the two works. The suggestion of games brings us to the notion of temporality and progression; the slight difference between each play of the generic game reconfigures the genre and influences games to come; but, although we see difference between plays, do we see any alternatives to the state of play? To posit alternatives is to conceive of a progressive development; to posit differences is to conceive only of repetition. Within the multiple possibilities that the game brings into play, there will always be alternatives.

|

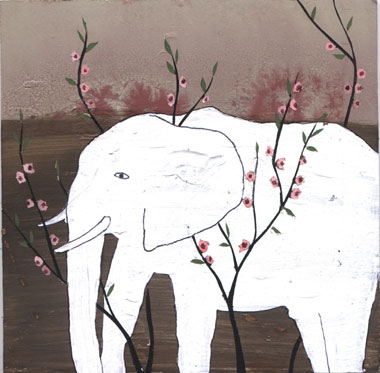

| Royal Art Lodge: Untitled, 2004, mixed media on panel, 15 x 15 cm; courtesy Douglas Hyde Gallery |

The compact paintings made by the Royal Art Lodge read as single ‘thoughts for the day’, and, at first sight, display a similar naivety. But, unlike the desperately life-affirming attitude of the latter, Royal Art Lodge forego any straightforward didactic function to these images. Instead, this series of disparate episodes treads lightly across what are traditionally the most profound of themes – death, war, friendship, sin, cruelty, remembrance, et al. – twisting the conventional representation of these themes into enigmatic allegories, all with a certain adolescent irreverence. If nothing else, it is good to see, in the midst of work often preoccupied with contemplating its own navel, collaborative work that seems to preclude many of the ‘problems’ of individualism being chewed over by others. The Royal Art Lodge use a drawing process rather like the Surrealists’ game ‘exquisite corpse’ where a drawing is begun by one member of the group and continued in turn by the others until ‘completed’. This produces, from what Max Ernst called the ‘mental contagion’ between group members, hybrid and absurd forms.

|

| Royal Art Lodge: Untitled, 2004, mixed media on panel, 15 x 15 cm; courtesy Douglas Hyde Gallery |

With a similarly dark humour, Peter Doig’s series of three Alpiniste paintings show a Harlequin figure trudging up a steep alpine slope, oversize skis across his back. The Alpiniste, caught in his lonely, laborious pursuit of thrills, cuts a pathetic figure; and a romantic figure, of course, a wayfarer and clown searching for unattainable, personal pleasures. But the Alpiniste seems more likely doomed to repeat his folly and return to the bottom than to experience sublime moments of expression in isolation on the piste, though it could go either way (‘and when they were only half way up, they were neither up nor down’). Yet one cannot ski without snow, and it appears to be the wrong season for it. Doig’s other two paintings, Untitled and Untitled (Paramin), show two monstrous figures – one ‘male’, one ‘female’ – emerging from what might be either dense undergrowth or heavy stage curtains. Flashing a grimace to the crowd, undead in costume, and ridiculously grotesque, they announce a macabre show: a parade of masks and perverse personas giving a semblance to the truly monstrous and perturbing those normally worn.

Kai Althoff’s mad and beautiful spray-painted daydreams of doves and seedpods come from somewhere else entirely, unexpected and anomalous in the context of the show, and from this position they open onto other realms of expressive possibilities. The figures permeate through one another, neither independent nor subsumed within a group, and with Althoff’s use of the rather anonymous technique of spray paint and templates the artist himself departs from expected positions. Perhaps with such slight deviance (also a feature Althoff’s broader interdisciplinary and collaborative projects) one can begin to see through, or around, this alleged need for isolation or withdrawal in order to become ‘oneself’. If they were not so fascinating these paintings would be embarrassing, but nonetheless, perhaps the latter is a prerequisite for ‘letting go’ one’s sophistication.

|

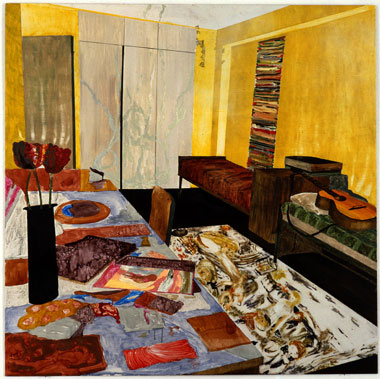

| Mamma Anderson: Pojkamas rum / in one’s sleep, 2002, oil on panel, 122 x 121.5 cm; courtesy Douglas Hyde Gallery |

In view of the above, the paintings of Mamma Andersson and Tal R seem rather conventional. The former’s take on the familiar theme of ‘the artist’s room’, Pojkamas rum / in one’s sleep, suggests a conflation between dreaming and ‘constructing’ one’s surroundings through painting, and that this ‘room’ contains traces of the discordant play of half-thoughts and half-finished artistic activities. From such intense activity, no doubt, art is made, but there is a lack of complexity here that cannot fully engage with the question of cognition through painting. Tal R’s The yellow, the pink, brown and green gives a rather clichéd image of ‘madness’: winged ‘night shapes’ swarm over a fiery red base. The great merit of this painting is its possible reference to the Captain Beefheart song Brickbats . According to legend, Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band, when recording their album Trout Mask Replica, did indeed ‘get lost in their ‘hut", locking themselves away for some months in an isolated farmhouse with nothing but beans and acid to sustain them. And they returned with "impossible slang and pearls, telling stories from the outskirts of that wonderful place we call the mind" (press release); but to simply illustrate what they returned with is, in a way, to betray that mixture of irreverence, talent, luck and madness that enabled them to return with anything at all. Furthermore, one must not forget that theirs was a collective withdrawal, and the ‘success’ of an album like Trout Mask Replica is more the result of the discordance and clash of rhythms that one would expect from a group of people holed up in isolation for months on end than it is the fruits of some putatively individual endeavour.

Tim Stott is an art critic living in Dublin.