In response to a world that is, for some, more intricately connected than ever, reticular metaphors prevail in contemporary art. Yet the complexities of this world – its financial markets, information and transportation networks, social relations, and so on – exceed figuration and its shifting spaces are opaque to conventional means of representation. In such a situation it is claimed that mapping is no longer a matter of describing the surface of the globe but of reconstructing a scene that has been lived through. This means that cartography comes back down to earth, so to speak. That sovereign power which once surveyed the world from on high, dividing out space, giving measure to it, and more often than not asserting proprietorial and territorial rights over it, is unsustainable: its panoptic eye sees from nowhere, which is, of course, impossible, and the knowledge which it claims of the world is detached, reductive, a fiction. Even if it were possible to occupy this elevated surveying position for a moment, one could hardly breath in its rarefied air. The cartographer who comes back to street level, where the air is, for the most part, breathable, immerses him- or herself in specific situations, the topography and horizons of which are set by social conditions to which we are all subjected, not least those of memory and architecture. It is these conditioned and situated experiences that might now provide material for maps.

|

| Franz Ackermann: Untitled (mental map: for security reasons, no water allowed), (Faceland III), 2003, mixed media on paper, 13 x 19 cm: courtesy IMMA |

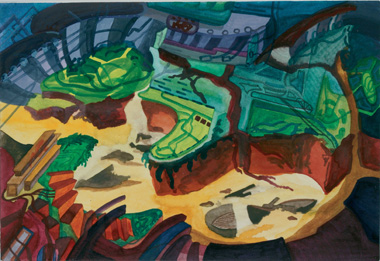

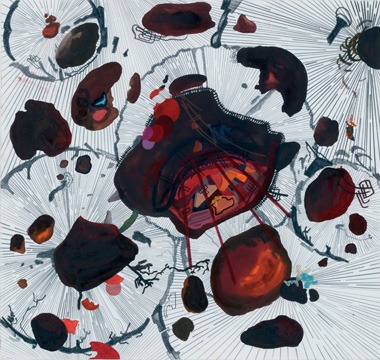

Franz Ackermann’s small-scale mixed-media sketches, which he calls ‘mental maps’, develop from his wanderings at street level. He plays the backpacking tourist, treading the well-worn paths of packaged itineraries, seeing the sights. In Faceland III, these mental maps interlace with wall drawings depicting dislocated quasi-architectural planes, and with a large metal globe suspended from the centre of the ceiling. The maps configure delirious, almost hallucinatory, impressions of familiar exotic locations (in this case, Venice) which, having left their traces through the diffuse and nebulous realm of memory, return in the appropriately fugitive medium of mixed media and pencil: sketches of tourist spots, fragments of architecture and landscape, combine with scrawls and abstract passages in pop colours, all painted with intimate density and depth. Such sketches articulate something of the fashionable retreat into the self and its mnemonic processes that is made in response to the uniformity, asocial mediations, and solitary individuality of what Marc Augé has called the ‘non-places’ of supermodernity (e.g. airport terminals, conference suites, tourist resorts, refugee camps). It is the experience of these ‘non-places’, allegedly devoid of history and anonymous, that provides Ackermann’s main subject throughout this exhibition.

|

| Franz Ackermann: Untitled (mental map: the new parking lot), (Faceland III), 2003, mixed media on paper, 13 x 19 cm: courtesy IMMA |

Urban wanderings have a long tradition in art, from the Surrealist street adventures of André Breton et al, right up to present-day artist-globetrotters such as Pierre Joseph and his ‘memory maps’. Most commonly drawn upon is the notion of the dérive put into practice by members of the Situationist International throughout the 50s and 60s. However, it should be noted, once again, that not only were the Situationists not interested in producing art as the end result of their ‘aimless vagabonding’, they were, in fact, anti-art, and the dérive was a collective activity that did not allow for autobiographical representation or personalised memory – it was a means of losing one’s way. Pseudo-Situationism is common in the visual arts, often simply to "spice up descriptions of otherwise politically tame art practices" (Simon Ford). Where the Situationists sought to open up a homogenised urban space by following the vagaries of their collective desires, Ackermann, by all accounts, is systematic in his wandering, preferring not to get lost: hence, he encounters a space that is everywhere the same, always thought out by others, one might say, however much it is refracted through personal recollection.

|

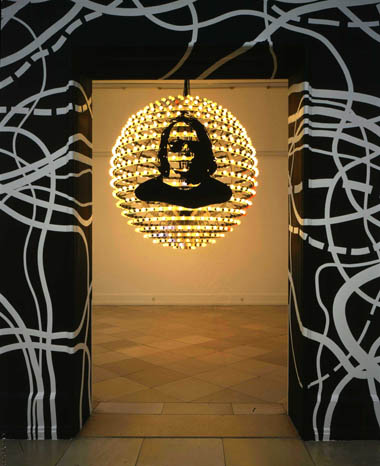

| Franz Ackermann, Faceland III (you better keep the light on), 2002, aluminium, light bulb, light, metal, ca ø 280 cm, Installation view: Kunsthalle Nümberg, 2003: courtesy IMMA |

The metal globe is bedecked with light bulbs that flash off and on in varying patterns: disco-demolition ball, neon logo, RKO antenna, and self-portrait in one, gouged into the globe’s surface is the image of Ackermann himself, complete with the apparently obligatory RayBans of the wealthier tourist. The bulky presence and symbolic mischief of the globe provide an intelligent foil to the subtleties of the mixed-media images. All the other works in the room interconnect around this artist-logo, centre-stage; aptly so, inasmuch as "[Ackermann’s] mental maps have their origin in the solitary figure of the flâneur, who observes the spectacle of the street in silence" (GNS, Palais de Tokyo, 2003; my translation). The flâneur eyes up the phantasmagoria of the streets, aloof yet discerning, at once in and apart from the crowd that surrounds him and offers itself up to him as a spectacle: he is "the passionate spectator, whose home is in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, amid the fugitive and the infinite" (Charles Baudelaire). His eye is both covetous and erotic, and it considers the city to be immediately available to its aestheticising gaze, rather than under continuous and incomplete social construction. But, most importantly, he (and it is always ‘he’) occupies an ambivalent position as at once bohemian rebel, privileged itinerant, and producer of commodities. Because he is "the observer of the marketplace" he is also "a spy for the capitalists […] He takes the concept of marketability for a stroll" (Walter Benjamin). That is to say, by virtue of his bondage to them, the flâneur comes to embody the fluid commodity forms of the marketplace: as a producer of cultural commodities, he peddles the latest ideological fashions – "his last incarnation is the sandwich-man" (Walter Benjamin).

So, when Ackermann assumes the position of a contemporary flâneur, scavenging the world’s cities in search of diverse, exotic impressions, he also appears at the vanguard of that great equaliser of difference, the marketplace. The means of the "passionate spectator" with the possessive gaze, the voracious consumer who regurgitates local peculiarities as tourist hotspots, and the globetrotting artist in search of material converge. No wonder then if Ackermann finds his own ever-shrinking world looking increasingly homogeneous; no wonder if he discovers little but spectacular clichés. The flâneur surveys the artefacts of his own alienation, whereas his pessimism, his detachment and his means of representing them become just more commodities. Yet he also conjures beautiful fantasies from the rubble. Precisely because he does not negotiate these and other contradictions inherent to his assumed position, Ackermann’s flânerie remains half-baked. It was the archetypal flâneur, Charles Baudelaire, who claimed that in the city nature was to be rediscovered or conjured up in its old richness and depth where it was most absent, in artifice – nature’s ‘final fruit’. During those exceptional moments when artifice becomes complete and perfect, it and nature coincide. These moments are rare, of course, and "the price of artifice is spleen, a grim and dreary conviction that the world has nothing to show us, a ‘gloomy incuriosity’ which is bound up with the collapse of nature. Spleen is the usual resonance of experience, the world’s deadly mimicry of our own lassitude and despair" (T J Clark). It is only in a handful of mixed-media pieces that Ackermann invokes a revivified nature via the refinements of artifice. Elsewhere, it seems that spleen prevails, and once again it becomes hard to breathe: "the sky is a lid, the earth is a cell, rain imitates the bars of an enormous gaol" (T J Clark).

Baudelaire, of course, was writing at a time when the notion of the ‘exotic’ was still available as a foil within the structures of reference upon which the self-identity of the West was constructed. Today, however, as the notion of a differential relation between centre and periphery is acknowledged for the patronising world-view that it supported, and becomes further outmoded under the conditions of globalisation, the term ‘exotic’ also seems redundant. Distance from the centre is no longer such a defining characteristic in those parts of the world that are ‘networked’ (lest we forget, these ‘networked’ areas are in the minority, in number if not in power). As Manuel Castells has noted apropos the ‘network society’:

The topology defined by networks determines that the distance (or intensity and frequency of interaction) between two points (or social positions) is shorter (or more frequent, or more intense) if both points are nodes in a network than if they do not belong to the same network. On the other hand, within a given network, flows have no distance, or the same distance, between nodes. Thus, distance (physical, social economic, political, cultural) for a given point or position varies between zero (for any node in the same network) and infinity (for any point external to the network)

This means, not least, that the search for the exotic is more often than not thwarted by the very means (the network of international tourist travel, finance capital, etc.) that make it possible. The determining logic of this network displaces the specifics (architectural, cultural, et al.) of the localities in which it is constructed: in order to flow, to move swiftly and without friction, the specificity of those supports that link up the locality with the network must be disavowed. In light of this, the desire for the exotic seems not a little utopian, based as it is upon a frontier mentality and an awareness of the real difference that comes with distance. This is not to say that the networks are absolute, closed systems (and if they were, would their artifice not have all the richness of a ‘second nature’?), or that there are not multiple positions within them, rather than pseudo -differences between one position replicated over and again. There are dislocations throughout networks, and their space is not static but constructed moment-to-moment in particular social situations, which opens these networks up to possibilities beyond the present configuration. But as Ackermann hitches a ride through what he apparently considers to be the closed network of global tourism, it is he who remains closed to possibilities, even when his transatlantic flight is disrupted by a bomb scare and he is forced to spend a few hours in the heart of the Celtic Tiger, an experience described by a series of photos in The Landing Room . (Here, Ackermann opts for straight photojournalism of the most uninteresting kind, trusting that the rather special anecdote surrounding these images will invest them with more than holiday-snap significance: it doesn’t).

.jpg) |

| Franz Ackermann: 1,2 fly, (travelantitravel), 2004, wallpainting; c-print, ø 140cm, framed in aluframe: courtesy IMMA |

Furthermore, as with so many of today’s globetrotting artists, Ackermann’s privileged mobility is uncritically assumed (either by the artist himself, or, more often, by those who write about him) to be ubiquitous and representative of a universal phenomenon. This means again that local difference remains largely ignored or obscured; yet it is here that the global comes down to earth in the local, that its virtual fluidity comes up against some resistance. Whilst Ackermann certainly does not celebrate "the triumph of urbanization or the modern nomadic existence intrinsic to an ‘international lifestyle’," as many do without a second thought, he fails in his attempts to "unflinchingly criticise the smooth circulation flowing back and forth between the world’s hemispheres" (Harald Fricke). Too often he simply replicates that space of spectacular immediacy and perceptual saturation that is said to characterise global capitalism at present. Yet once again, it is precisely from the discontinuities within this environment, and, more broadly, the element of chaos that is intrinsic to space itself, that ‘unintended consequences’ arise.

|

| Franz Ackermann: untitled (mental map: values of the west), (Faceland III), 2003, mixed media on paper, 28 x 29.6 cm: courtesy IMMA |

Contemporary space is not two-dimensional, self-same and circular: it cannot be a ‘flat’ surface, "because the social relations that create it are themselves dynamic" (Doreen Massey). Space is four-dimensional: however complex and intricate it may be, however simultaneous the relations between its parts may be, it still has extension and configuration through time, it still has depth . Within this space, human activity does not assume a total ‘tele-presence’, capable of being here, there and everywhere at the same time, as Paul Virilio would have it: there remain very real obstacles and limitations to the sphere of activity, whether this be in real time, recorded time, or the recalled time of memory. Granted that Ackermann’s resources are circumscribed by the two-dimensional nature of his medium, but when this two-dimensionality is asserted in psychedelic explosions of cosmetic colour and ‘flat-packed landscapes’ that could derive from anywhere and, most importantly, from anytime, it falls short as a metaphor for the four-dimensional experience of contemporary urban space.

There is an ambivalence to brilliant colour, of which Ackermann’s almost fluorescent, dizzying combinations explore only one side. Ackermann appears to use colour according to the traditional criticism that it is cosmetic, deceitful, all surface and make-up. In many cases these qualities made brilliant colour the mark of modernity, which has also been characterised as without depth and without a centre that holds. But perhaps there is an aspect to colour that is more powerful than that of cosmetics. Colour is also the power to dream: freed as it is from both the Law and Nature, it is intoxicating, seductive and full of promise. This promise may no longer be quite the life of luxe, calme et volupté, but the descent into colour still offers some means of contact with what is not-self, and with what is not mere surface, even if it is represented in the cosmetic medium of painting. Here is Paul Cézanne on how to look at paintings:

Shut your eyes, wait, think of nothing. Now, open them … one sees nothing but a great coloured undulation. What then? An irradiation and glory of colour. This is what a picture should give us … an abyss in which the eye is lost, a secret germination, a coloured state of grace … lose consciousness. Descend with the painter into the tangled roots of things, and rise again from them in colours, be steeped in the light of them .

This world of simple, unmediated sensations, uncorrupted by interpretation was always delicate and vulnerable, and, by now, it has been decisively shown to be unavailable to us. Yet this deep luminous reverie, this ‘coloured state of grace’, although it might lack the newborn innocence that Cézanne hoped for, might be better compared to the flight of "a brightly coloured bird, hovering over the horrors of a bottomless pit" (Baudelaire). This slight fall holds off a greater fall; the dream undoes the nightmare.

Lastly, for those artists who are discontented with the present state of affairs – whether or not they speciously claim, as Ackermann does, to be ‘apolitical’ – perhaps it would be more effective to engage in what Saskia Sassen has called "spatialised power projects," or what Doreen Massey has called "power-geometry." Both argue for a progressive and historical sense of place that cannot be reduced to the static uniformity and isolation of ‘non-place’. After seeing Ackermann’s show one is left wondering whether the artist has really inquired into what this might mean for painting which aims at topographical representation and the reconfiguration of lived experience through memory.

Tim Stott is a critic based in Dublin.