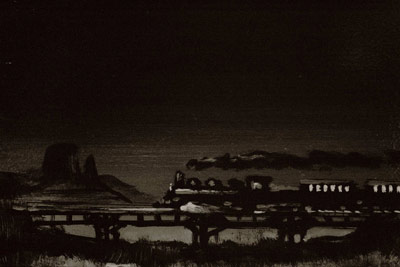

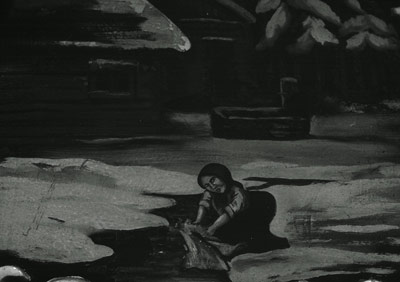

Peter Fischli and Davis Weiss like to play games. But what’s a stake in their playing is not merely to win or lose – that is, the game itself, but rather the way they can use an arbitrary-seeming structure, which is, fundamentally, an effort to uncover the strategies of knowledge and influence that move under the placid surfaces of cultural exchange. Theirs is the revealing humour of the bad joke or street-corner card-sharp, and the installation of the work Fotografias at the Douglas Hyde Gallery is a case in point. Arranged on makeshift tables with a series of ‘panels’ on each, as well as a number of individually framed images on the walls, these darkly toned images are presented in such a way that presupposes a connection to the format of the popular comic or of graphic novels – not least because many of the images feature characters and scenes already familiar from the iconography of that material. We are told, and indeed it is obvious from looking at certain of the pictures, that these are photographs of fairground rides – or more specifically, the painted, narrative decoration that adorns each contraption, suggesting a theme for the experience: buy the ticket, take the ride.

Initially, it seems like the work is presented as a ‘typology’ to document and compare the different characteristics of each painting, as if admiring the style of some lost, anonymous master. Of course, this classifying strategy has been widely popular over the last few decades or so in photographic work, but beyond that first impression it is clear Fischli/ Weiss have gone to deliberate efforts to frustrate any kind of assumption that could be made about each photograph – their murky lighting and the complete lack of context ensures that these are most certainly not documentary images, but something aimed at opening up the language behind the painted subject, behind the stories they tell, to see the cultural drift that moves these particular images. They want to chart the uncertain spaces of shared knowledge, how visual ‘languages’ can develop and, working like archaeologists, they want to see if these systems can be reconstructed when only partial or corrupted elements of the whole remain. To this end they use the familiar panel layout of the tables to construct a loosely thematic series for each, where the content of the painted source images allow them to illustrate certain archetypal narratives of a kind mainly drawn from comicbooks and fairytales – the damsel in distress, let’s say, or the young man facing some unspecified danger, with symbols both arcane and obvious thrown in for good measure. Really what seems to be at the core of this work is their tracing the archetypes of traditional narrative forms into the omnivorous discourse that is our ‘information’ age, where cultural knowledge is not shared, but atomised, and their approach to how the work is presented would seem to mirror this process of ordered fragmentation.

Yet in many ways the sheer accumulation of images, of data, is counterproductive – it only serves to obscure the very subject they are trying to explore: the way pockets of narrative move across a culture, how stories are told and what gives then structure. So while the installation and how the viewer must explore it are quite intriguing, the project as a whole never seems to embody the potential of its conceptual premise; that original rigour is lost in the proliferation of images. Of course, this might seem rather like the point of the work, but one can’t help but feel that there is an elegant and serious artwork within the contrivance of its present structure – an excess of structure perhaps, its seeming relevance not withstanding. Most eloquent are those images which include stray details of the carnival rides themselves, rivets and metal seams or cracked, flaking paint – ruptures in the narrative fabric, pointing to the contingent nature of those stories that hold a culture together. Had the artist’s structural ‘game’ been able to demonstrate the entropy that is so deftly implied by these pictures, instead of the tired formulas of repetition drawn from popular media, this body of work might have achieved something that was, in its own subtle way, extraordinary. As it stands, of course, the exhibition could not really be called a disappointment, in so far as it contains much of the artists’ trademark wit and formal inventiveness, yet it is hard to escape the impression that what we are seeing is really just a clever game, a diversion and little else.

Darren Campion is a writer and photographer.