If memories and films are often associated – in imagination we visualise our memories as akin to a film projection, for instance – it may have something to do with a shared elusiveness. A film is always somehow happening in between two photograms and memories unpredictably unfold around objects or places. Both elude our grasp.

At the heart of Fiona O’Dwyer’s body of work Strange the rooms we’ve all lived in, there is a film: Desmond Davies’ I was happy here (1965), and there are memories: of the film in the making but also memories of the artist: of another film, of another place. Through series of performances, installations, projections, and various – mostly analogical – processes: printing, etching, drawing, filming, recording, the artist seems intent on inscribing, on embodying film and memories.

As the catalogue accompanying the exhibition suggests, the works on show in the Courthouse Gallery and in the town of Ennistymon are only the latest part of a body of works that has developed over two years with I was happy here as its Ariadne’s thread. The film, scripted by Edna O’Brien and partly shot in Ennistymon and Liscannor, recounts the return of an unhappily married young woman to the Irish seashore resort where she felt happiest. She romantically associates this happiness with her love affair with a fisherman. Confronting her memories, she realises her delusion but finds joy in the sea air, on the beach, in the music, and seems to reach a better understanding of her longings. Strange the rooms we’ve all lived in – it is a line from the film – engages with both the diegesis (the narrative content) and the exegesis (the making) of the film.

The association of the film with Ennistymon and Lahinch beach echoes through the work: as the film was shot on location its making has left traces: props which have been kept by the inhabitants of the area, sets that were stored in someone’s shed for forty years, memories of the shoot itself, such as Sarah Miles being permanently attended by a make-up artist, and, obviously, the places’ presence in the film. O’Dwyer overlays the realm on-screen and the one off-screen in staging projections of film-stills with the props and sets used in the making, whether a bicycle or a bedroom set. The film was also shown in Ennistymon’s main street, which has a scene practically to itself, thus creating a mirror effect for the viewers.

Another form of appropriation is the re-enactment of certain scenes, such as the bicycle rides, for the two-channel video projection Endless return: the artist repeated two rides from the film, one on the beach and one in London, on Lahinch beach. Rather than simply reproduce the scene, she tried to recover a visual impression, the light atmosphere which permeated the film scene.[1]

A London scene, in which the heroine feels most acutely her alienation and loneliness while standing in front of a shop window filled with television sets, is the starting point of a performance, in turn leading to two installations. O’Dwyer set up sixteen television sets on Lahinch beach to form a stage for her singing of Oh Danny Boy. A recording of her singing as well as the elements of the performance – the magnetic recorder, the fur coat and the television sets – were composed into two installations in shop windows accompanying the Courthouse Gallery show.

Her working through the film’s impressions seems to have unlocked some form of methodology for the artist to engage with her own memories. They are more directly addressed in the photographs, drawings and prints occupying the ground floor of the Courthouse Gallery. A series of drawings attempts through tentative tracing to shape memories on paper, mapping an event as in What happened that night, or placing a moment such as another singing of Oh Danny Boy.

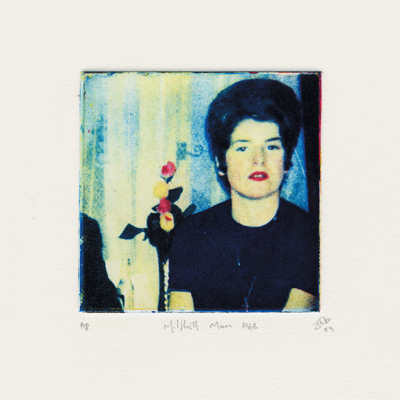

A series of colour photo etchings, made from 1960s photographs of O’Dwyer’s family, take form as coloured fragments of her past. They are identified by their location and date, Valentia ferry 1965, Balinagleara interior 1965 or Millhill Dad ‘64 but what she tried to inscribe through the printing process is rather a coloured sensation distinctive to 1960s photographs. The drawings and the etchings share a certain sketchiness, their scratched surfaces bear the traces of an attempt to scrape off the literalness – of the photographs, of the narrativity of the event – to reach for the texture of memories, whether a colour, a sound or a movement.

The photo etchings were also used for several outdoor projections and for lighting the objects that are the subject of the five large photographs that occupy the central space of the gallery. The objects, which are rather small – a purse, a syringe, a heart-shaped vessel, a bottle and a comb – and have an intimate connection to O’Dwyer’s past, are given an almost monumental presence through the magnified scale of the photographs. Staged, described by sand-blasted words and hallowed by the light of the past they seem to belong to, the objects are re-inscribed into a perspective.

Strange the rooms we’ve all lived in composes a complex body of work through multiple media, interweaving the world of I was happy here and the artist’s. Beyond the sharing of a place, Davies’ film and O’Dwyer’s recovered memories have a common concern with the sensation of light and a certain affinity with words, but maybe more crucially with what constitutes a memory, how a place or an impression is remembered, how deluding memories can be and ultimately what constructs an identity, and how.