|

| Brian Walsh: Field (detail); courtesy the author |

In 2003 ‘art / not art’, of which I am a member, and an architectural historian, Katherine McClatchie, took on the task of curating the annual exhibition in St. Finbarre’s, Cork, Art in the Cathedral . It had been a year in which history and the global extension of our social practices had erupted into daily life. A critical moment had been generated by the invasion of Iraq, throwing into relief the terms by which societies in the West were sustained. The political agency of the people, the demos on which ‘free democracy’ rests, was both actualised and disengaged by the protest marches and their effect. The objectivity of our international perspective was severely questioned by the clearly compromised nature of television coverage of the war, at the same time as the objective gaze of tele-surveillance technology was shown to be refining itself at alarming rates. The spectre that had haunted the last century’s cusp, imperialism, could be seen yet again floating along the corridors of power, with Halliburton and Chevron Texaco replacing the likes of De Beers and Siemens. More frighteningly, that extension of imperialism into home-state government, totalitarianism, had seemed at its closest in the United States since McCarthyism, if only for brief, hysterical moments. And Ireland was in the midst of it, afraid to object to the U.S.’s use of Shannon lest American companies withdraw their investments.

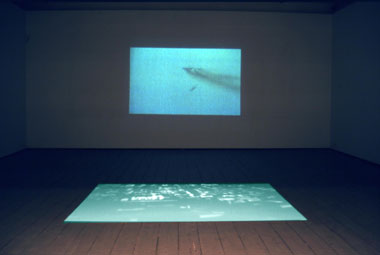

In this electrically-charged environment it seemed impossible for us as curators not to forefront art that in some way tried to come to terms with the sense of crisis and shift in social experience that was daily beamed into our living-rooms and shouted from the front of newspapers. One Irish piece of recent years that immediately came to mind was Brian Walsh’s Ground Zero II (B52 Fly-Over), which we had seen at the Salah Hassan-curated ev+a 2001 . The award-winning piece (which was given its title before September 11) involved two video projections in a darkened room of the City Gallery. On the wall facing the viewer a shadowy B52, seen from behind, maintained an endless trajectory through a grey vaporous space, while at the viewer’s feet what looked like a city, at night but without any illumination, scrolled past as if viewed by the passing bomber. It wasn’t necessary for the viewer to know that the image of the city had been made using a scale model of Cork, to be aware that the felt sense of threat related to something familiar, that the shadow of the plane did not pass across the usual exotic topographies. Which is to say that it ‘brought home’ something that until then simultaneously presented itself in our domestic interiors while remaining safely separated from us by thousands of miles. Graphically direct to the point where any easy literal translation was ‘pre-empted’ (to use a phrase from the vocabulary of war), Ground Zero II effectively married the presentational techniques of contemporary gallery-based art to the phenomenology of ‘foreign crisis management’.

|

| Brian Walsh: Revelations Chapter 9; Verse 1, installation shot, Linenhall; courtesy the artist |

On entering the foyer of the Castlebar exhibition I re-encountered the piece that Walsh eventually submitted to the Art in the Cathedral show, Revelations Chapter 9; Verse 1 . Perched in an alcove above the visitor’s head, a Victorian plaster monumental figure, of a guardian angel protecting a child, altered so that the angel’s upward-pointing hand carried a satellite dish, looked down towards a monitor on the floor showing the meteor-like, disintegrating Space Shuttle streaming through a bright blue sky. Even without Walsh’s interesting notes (apparently George Bush Jr. after the Shuttle disaster, aware of an apocalyptic reference to falling stars and the opening of the bottomless pit, explicitly responded to the omen in his next press release with a reference to the Old Testament), it is an intriguing, even meditative piece. Especially in the twilit aisles of St. Finbarre’s, where the conjunction of angel and technology had an immediate resonance, the slow drifting of the star / spacecraft and the calm demeanour of the angel had an almost mesmeric effect. That said, I was not altogether happy with its re-appearance in the Linenhall. The relatively short electrical lead linking the dish to the monitor in St. Finbarre’s, blue so that it echoed the sky-blue of the monitor as the angel’s snowy whiteness corresponded to the incandescent Shuttle, had been replaced by an obtrusive black and lengthy wire (it had to reach from the alcove to the ground). More importantly, making my way through the main part of the exhibition, it became apparent that a certain thread of thought ran through the rest of the pieces but bypassed Revelations, so that I couldn’t help feeling that the piece’s presence was something of a distraction.

|

| Brian Walsh: Ground Zero II (B52 fly-over), 2000, dual video projection (installation shot at ev+a ); courtesy the artist |

The successful establishment of the ‘marriage’ that I mentioned in reference to Ground Zero II, a bind between aesthetics and politics (which I have tried to unite in the ‘ethics’ of this review’s title), depended on two main factors: the interchangibilty of the shadowy, ‘artistic’ video-projection and the blurred images commonly sent from military aircraft; and the use of the topographical model. In the Castlebar pieces apart from Revelations, one or other of these two fusing factors, the targeting image and, to an even greater extent, the use of ‘scale models’, was brought into play, so that a sense of continuing inquiry led through the pieces, back to Ground Zero II . This connection was made explicit by a series of digital prints, stills taken from Ground Zero II, mounted on the wall of the main upstairs gallery. Blurred images of sections of the scale-model of Cork simultaneously worked as pleasing semi-abstract tableaux, cool and geometric, and presented the distanced, dehumanising view of the managerial surveillant, or ‘Globemaster’, to use the name of a U.S. military aircraft. Near these Reconnaissance pieces, a print entitled Time line showed part of a still taken from television images of long-distance air-strikes, a blurry pale block (a building? a target in an antiquated computer-game? a model intended for a sculptural presentation?), brushed by the cross of a targeting-sight, emitting a puff of smoke. But Walsh is primarily a sculptor (albeit one of the post-Nam June Paik age) and the most arresting elements of the Linenhall exhibition were three-dimensional.

|

| Brian Walsh: from Reconnaisance; courtesy the artist |

The question of scale, that question of the ‘ladder’ (to allow the Latin root its resonance) that leads up step by step, conceptually or physically, out of immersion in a space and allows overview and control, is one that clearly bears on both modern politics and art. The modern era in politics is an era of maps, of ordnance surveys and satellite geo-positioning; that stripped-down use of the bare, white gallery space introduced by Minimalism, that awareness of an environment of extensional proportion, is a fundamental underpinning of post-sixties, nontraditional art. For each scale is essential. What Walsh’s art is attempting to do is find occasions of that play of scale that manifest the interconnectivity of the two. Minimalism, though born in the middle of the Cold War, generally concerned itself with a detached, conceptual intervention in the history of art (newly re-aligned by Clement Greenberg), and much of that flood of post-Minimalist installation, which yet has to resolve itself into any jointly held current of concerns, has the habit of taking for granted the aesthetic space opened up by Minimalism (and Conceptual art), occupying it like a gang of placard-bearing minority activists, would-be celebrities and techno-futurists. In such a general environment it is refreshing to see that Walsh’s sculptural pieces try to adhere to a bind between reference to the greater world and the bare terms of the Minimalist space, suggesting that some kind of inner connection may exist between the two.

This is the purpose of the ‘model’ in Walsh’s work: it succinctly represents the working of ‘scale’. Since ev+a Walsh has settled upon a particular model for his purposes – a ‘domestic unit’, a white wooden block of varying size with a pitched upper surface, a scale model of a suburban house and a simple sculptural form, to be arranged in the gallery space like a Sol Le Witt ‘cube’. Vanishing point II, which was arranged in the upstairs corridor of the Linenhall leading to the main gallery space, clung most closely to these Minimalist aesthetics. ‘Domestic units’ were arranged along sets of lines fanning out from two originating points, the size of these units being determined by a perspectival logic – the units were scaled-down as they approached the two ‘horizons’. Where the fans of units, ‘cubes’ or ‘homes’, intersected, there was an area of turbulence, the carefully controlled geometry being thrown into semi-managed disarray. It is a simple piece, satisfying in an abstract way but also, because of the unavoidable associations of the ‘domestic unit’, generative of its own kind of connotative ‘turbulence’. Not only is the viewer encountering a neutral display of mathematical aesthetics, but he / she is ‘standing above’ (on the ladder of scale) an arrangement of ‘houses’. Immediately an abstract geometry becomes a matter of power and magnitude: the arrangement is a mode of controlling something social – that is, something that involves human dwelling and co-existence – from a distance which implicitly dehumanises the ‘society’ involved. One imagines an urban planner, operating according to Le Corbusier-inspired principles of geometry and function, witnessing the quiet appearance of complexity in his schemes, momentarily losing control.

For me this brings to mind a somewhat shrill tradition of social analysis that begins with political philosophers like Hannah Arendt and persists in the present in the apocalyptic pronouncements of Paul Virilio. Central to this tradition is the idea that the nation state, the basic modern social organisation, is undermined by that growth in capitalist industry and enterprise, which it protects and encourages. In these terms ‘scale’ is a governing factor in the character of a society: beyond a certain size certain social organisations, which seem natural and reasonable, breed irrationality and tyranny. The age of imperialism (from about 1875-1914) is exemplary in this regard: violent economic expansion drove gunboat-backed capitalist industry into Africa and South America, while giant cities came into being on the home continents, filled with masses of unskilled workers. The nation-state with its various democratic institutions, in other words, found itself operating on the scale of an empire, confronted on the inside by a dark mass belonging to no traditional party (which was where various socialisms stepped in), and on the outside by the need to govern regions on the other side of the world. Much of our environment is the result of this predicament (and the catastrophic wars and regimes which it engendered). Our world is one where democracy protects itself against the ‘demos’ with closed-circuit television, while encouraging a depoliticised mass of media-led consumers, a democracy which manipulates regions of economic importance through powerful technologies of war, capable of picking out an individual human target several miles away, but not of telling whether that target is a child or adult, civilian or paramilitary. We have, on the other hand, Jamaican-manufactured jeans in our high-street stores, package-holidays in Tanzania and dazzling skyscrapers in China. Between flow the migrants, sometimes adding to the masses, sometimes not even reaching that degree of citizenship and protection, often guided by the very dreams of wealth that led in the first place to the disruption of their societies and their uprooting.

|

| Brian Walsh: Field (detail); courtesy the author |

|

| Brian Walsh: Field, installation shot, Linenhall; courtesy the artist |

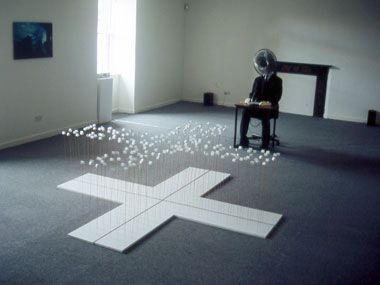

The sense of magnitude and a play of power that are evident in Vanishing point II are made explicit in the exhibition’s central piece, again in the main gallery of the Linenhall, Field . Here, for once, a source of the managerial power is made manifest. Appropriately, it is fetishised, made weirdly naturalistic in the midst of the semi-abstract prints and assemblages. Behind a desk a life-sized, besuited dummy, with an electric fan for a head, surveys a wavering rush-bed of small ‘domestic units’ on long copper stems. As the face / eye / fan tracks from one side to another, setting the units quivering, the low hum of a motor is heard, linking back to the drone of the aircraft in Ground Zero . The figure manages to be at once sinister and comic, a faceless executive performing a meaningless routine and a pagan idol, unattached to reason but emitting a power seen in the movement of the ‘houses’. It’s a piece that worked well in the room given it in the Linenhall as it, rightly, dominated the space. If I have any criticism it is that the main gallery leads immediately onto a manned office with only a glass partition between, so that the viewer never feels entirely on their own with the fetish. Apparently, on entering the gallery first thing in the morning workers in the arts centre were often startled to find it already ‘occupied’, to be confronted by a quasi-human presence that laid claim to the space, an effect that could have been amplified by using a room with only one entrance.

|

| Brian Walsh: Bliss, installation shot, Linenhall; courtesy the artist |

|

| Brian Walsh: Bliss (detail); courtesy the author |

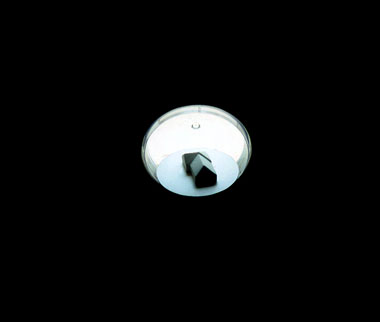

One thing remains to be explained: why this bind of politics and aesthetics should be termed ‘ethics’; in other words, what has it to do with how we as individuals conduct our lives? On this question another anecdote related to me when I visited Castlebar comes to mind. Walsh’s show spent some time in Westport before moving to the Linenhall and, at the Westport opening, a local approached the artist and commented admiringly of the Field piece that it spoke directly to house-builders in the region, who found themselves continually thwarted by planning regulations. The figure at the centre of Field could be read, in other words, as a planning officer, a stickling bureaucrat as far as the locals were concerned, exercising an unreasonable power over the people’s natural demand for housing. In the corridor leading into the main gallery, near Vanishing point II, a counter-argument could be found. Bliss 191, 192, 193 (another Walsh title that sounds like a military designation or directive) utilised three small windows that looked out on the foyer. These had been blocked, leaving only a circular hole in the centre. In each of the three holes a globe had been fixed, so that the only natural light in the corridor came through the globes. In each glowing ball there was a tiny model of a house, made so that they conformed to the specifications of three designs from the manual for standard bungalow-building, Bungalow Bliss : designs 191, 192 and 193, to be exact. The effect was to present these insignificant shapes in a way reminiscent of the snow-globe at the beginning of Citizen Kane, as micro-paradises, images of longed-for or lost perfection. There were problems with the piece, to my mind: it was far more effective at some times of the day than others (but then the same might be said of stained-glass windows); the globes had been recycled from plastic containers, made for containing novelties (with funding and time a version with specially-made glass globes could be realised); and iconic as Bungalow Bliss is, it has more contemporary and I feel relevant successors (the Plan-a-Home manuals, for instance). That said, the piece still worked and the concept communicated itself.

|

| Brian Walsh: Bliss (detail); courtesy the artist |

What it communicated was our complicity in this regime of scale that Walsh’s work investigates. Here were the very ‘domestic units’ that formed the building blocks of super-sized managerial politics, the dehumanised blocks translated so easily into the targets on the long-distance bomber’s screens, but presented with all the aura of desire that the New Ireland attaches to them. Driven by the spectre of eighties’ unemployment we have agreed to trade our hours of productivity for a wage – a guarantee of survival and a promise of freedom that is removed from us by the very living environment that the acquisition of that wage necessitates. Like the Good Witch in the film version of the Wizard of Oz, fulfilment recedes from us in its luminous bubble, to that place on the horizon after the hours in the open-plan office, after the computer is switched off, after the traffic jams and the inane radio, after the weariness, the glass of wine, perhaps, the quickly prepared meal and an hour or so of television. We are shunted along a ‘chain of signifiers’, to borrow a phrase from the poststructuralists, stations of desire that cannot satisfy in themselves: the weekend of liberation, fuelled by alcohol; the sunshine holiday; sexual encounters; marriage; a new four-wheel drive; emotionally burdened children; the cakey residence where someone who looks like us smiles at us out from the front door; retirement and a villa in Kerry or Spain.

Which is to say nothing new or particularly radical: it’s simply a matter of Ireland joining the revolution that began in the U.S. some time around ’53, an internal revolution responding logically to the external economic expansion. Where Ireland has made an individual contribution is in its emphasis on building: what is radical about the ‘Celtic Tiger’ is the determination of the majority of the population, developers and first-time house-buyers alike, to transform the inherited ‘land’ into a ‘property’, a transformation exemplified by the change of commonage into commercial enterprise at the Old Head of Kinsale. It is in accordance with this determination that the ‘domestic units’ spread, like Sol Le Witt cubes, across a landscape becoming more featureless, more like green or fairway, more like the terrain on a flight-navigator: estates and ribbon development out from City West, across the central plain, to where armed guards patrol the perimeters of Shannon. Which is only to point out that mounting the property ladder, like mounting ladders in general, is a matter of introducing scale.

Fergal Gaynor is a Cork-based writer, performer and member of the art-group ‘art / not art’, who were co-curators of Cork Caucus.