|

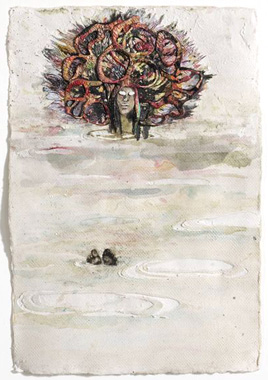

Ellen Gallagher: Watery Ecstatic, 2006, Watercolour, gold leaf, plasticine and cut paper on paper, 29.5 x 20 cm; courtesy the artist/ Hauser & Wirth/ Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane |

In this her first solo exhibition in Ireland, Ellen Gallagher showcases some excerpts from her ongoing series, Watery ecstatic . Based on a myth propogated by a Detroit-based techno band in 1997, Coral cities relays the story of Drexciya, an underwater world populated by the descendants of pregnant West African women forced off slave ships on the Middle Passage, from West Africa to America, whose unborn children adapted to the water in utero and began a species of half-human, half-fish creatures.

Coral cities is a joint effort between Tate Liverpool and the Hugh Lane Gallery, the show running from April until August 2007 in the Tate 08 series in Liverpool. The two citites involved are hardly incidental. Liverpool is a city whose historic prosperity was built on the profits of the West Indian slave trade, and the show in Liverpool is part of a series of cultural events commemorating the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the UK. Both Liverpool and Dublin share a history as ports of passage, and the meaning of the work is perhaps more apparent in the contexts of both cities.

Gallagher’s work may be most poignant at this moment, in this, an Ireland of shifting identities – not only the shifting identity of the nation state but the ambiguous individual identites created by the increasing integration of new cultures into our society. Gallagher restructures identity sterotypes by addressing the forgotten history of the almost 11 million slaves who never reached America and reconfigures this history in light of popular culture.

|

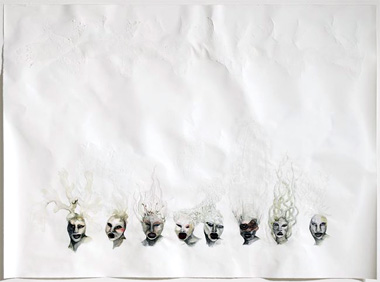

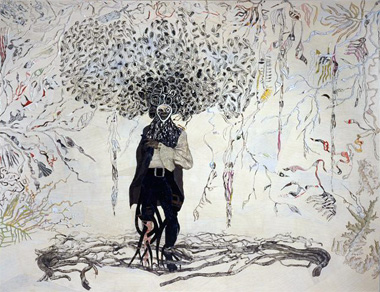

Ellen Gallagher: Watery Ecstatic, 2007, Ink, watercolour, crushed mica and cut paper on paper, 140 x 190 cm; courtesy the artist/ Hauser & Wirth/ Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane, Photo: Mike Bruce |

In taking on the 1990s myth of Drexciya, Gallagher constructs new cultural identities for the black woman, central to her own identity as a black Irish-American woman. Her own biography is in fact crucial to her oeuvre and to this myth. Gallagher’s family history, encompassing as it does the combined histories of Cape Verde and Ireland, is populated by islands, immigration, exodus, oppression and lost memories, and these are the chief concerns of her artwork. Throughout Gallagher’s work a strong, defiant and subtle voice calmly shines through – the kind of voice which can only accompany the quality of confidence that comes from resurrecting and giving credence to forgotten histories and with them recreating new cultural and historical figures.

Gallagher uses two different techniques to bring her intentions to fruition: puncturing and carving heavy-duty paper in her own version of scrimshaw, a sea-faring craft, and layering. She layers paper, plasticine, gold leaf, varnish, paint and more paper to create multiplicitous ‘drawings’ rich in imagery and meaning. In the same way that Gallagher layers canvas and paper, she layers meanings and double entendres. The rendering of linguistic elements in visual formats is a major concern, and phrases jump out of every image – “Beef,” “Splash,” “Change it,” “Black magic,” “just friends wearing a wig” – heightening the image’s potential for meaning or perhaps just the opposite. The images can be so directed by the words upon them as to curb the potential for interpretation

The imagery in this exhibition is of ethereal and imagined sea creatures with flowing dreadlocks, lustrous curls and rigorously teased afros. Gallagher sends up out-moded stereotypes of the black body; minstrel faces are repeated through an octopus’s tentacles, and full, swollen lips and bulging white eyes abound. Gallagher is best known for appropriating images of stereotypical black figures from mid-twentieth-century black-culture magazines such as Ebony and Sepia, and she satisfies expectations in this exhibition, as there are many references to the styles and ideas circulated by those magazines.

|

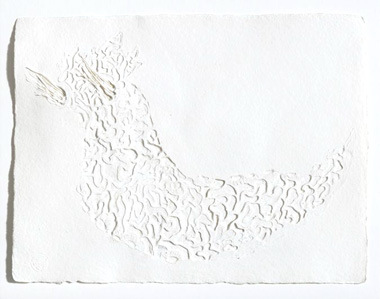

| Ellen Gallagher: Watery Ecstatic, 2006, Cut paper, 23.5 x 30.5 cm; private collection; courtesy Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane |

|

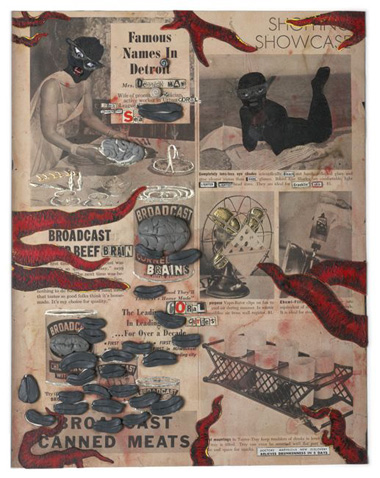

Ellen Gallagher: Watery Ecstatic, 2005, Watercolour, ink, oil, varnish, collage and cut paper on paper, 83 x 107.6 cm; Collection Nancy Lauter McDougal and Alfred L. McDougal; photo Mike Bruce; courtesy Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane |

According to Karen Fitzgerald [ 1 ], hairstyles have been a particular creative refuge of the racially oppressed in America, along with dance, music and speech, and this is why Gallagher uses the language of those promulgating African-American hairstyles in works such as Watery ecstatic, 2001. This cut-paper image is of a pseudo-island, the names of its ports carved into the paper and lifted from the aforementioned magazines – “Spiral luster,” “Page boy with bangs,” “Glamour bob” and “wiglette.”

In the spirit of early Dadaist attempts at feminism in art, a page from a vintage magazine has been distorted and defaced in Coral cities, 2007, and has become a newsletter for the black Atlantis, Drexciya, showcasing the “opticians wife” and “bikini eye sunglasses.” Words have been cut out and replaced with “bleach,” “cracklin’” and “light, lighter, lightest.” Plasticine brains and cardboard sea-tentacles have been attached and the scene teems with beans, beans and more beans (beans being the staple diet of the Middle Passage captives).

|

Ellen Gallagher: Coral Cities, 2007, Ink, watercolour, gold leaf, cut paper and plasticine on Ebony Magazine page, 32.4 x 25.1 cm; private collection; photo Barbora Gerny; courtesy Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane |

Bird in hand is the pick of the selection: an ample canvas layered with heavy lined paper, delicately carved and intricate paper seaweed, and centrally the image of a pirate, his medusa-like hair spawning voluminous images and phrases, his legs growing thick sea-roots and his distorted face defiantly rearranging stereotypes of the black face. Bird in hand is at once haunting and fantastic, the pirate’s face bold and challenging, whilst his hair and the seaweed swirling around him are beautiful and light. Juxtaposed with these already conflicting images are the words and phrases which jump out of the pirate’s hair: “free” is repeated numerous times along with “need money?,” “adjustable waist,” “sex education” and “black magic.”

|

Ellen Gallagher: Bird in Hand, 2006, oil, ink, cut paper, polymer medium, salt and gold leaf on canvas, 238 x 307 cm; courtesy the artist/ Hauser & Wirth/ Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane; photo: Barbora Gerny, Zürich |

Cherry Smith has said that Gallagher’s work is speaking “a language audible to every black person viewing it,” [ 2 ] but perhaps its reach is far greater, and it speaks a language audible to every person acquainted with the nuances of oppression, dispersion and unfair stereotypes. Gallagher’s work is the dextrous and fervent output of an artist confident with her message and her intent, the minimalist appearance of her work belying its suffusion of intellect and attention.

Hollie Kearns

1 ‘Ellen Gallagher Coral Cities,’ Fitzgerald, Karen, ‘A Challenge to History; Ellen Gallagher’s Coral Cities,’ 2007, Hugh Lane Gallery and Tate

2 Cherry Smyth, “Ellen Gallagher: Salt Eaters”, Circa, Autumn, 2006