Contrary to what might be assumed, the experience of blindness is ripe with questions for the visual artist. The exploratory art project Touchstone test piece stemmed from Shipsides’ desire to forge a visual language which represented landscape in a way that had less to do with sight and more with movement and the tactile. The artist worked alongside John, who had been partially sighted until he lost all sight fifteen years ago, researching his experience of climbing and his relationship to the landscape. The resulting exhibition, Echo Valley/ A guiding dilemma, serves as a compelling example of the benefit to artists of spending greater ‘time in the field’; the project’s ethnographic time-scale allows for a long-term dialogue between the two men and a developing understanding which it is hard to imagine would have emerged on a short-term project.

Shipsides chose a number of strategies to gather data on John’s experience of landscape. He attached micro-cameras to his fingers, backpack and feet in order to record ‘finger tip’ footage of his climbing, took more conventional video footage of John being guided on a climb and negotiating his surroundings in everyday circumstances, and recorded a number of conversations with him. In one of these conversations, the artist admits to a degree of naïvety, commenting for example that the strategy of tracking John with micro-cameras turned him into “a paintbrush.” Yet the work which results is not unsuccessful; it simply has different outcomes to those that the artist had initially anticipated.

|

| Dan Shipsides: Echo Valley/ A guiding dilemma, installation shot, Gallery 1; courtesy the artist |

In Gallery 1, the multi-screen video installation Echo Valley shows the micro-camera material of John climbing Little bootie, presented in a number of formats on three sets of dual screens, with all the material synced in time and drawn together by sound footage. This form has the effect of mapping the body of the climber; on two large inward-facing landscape-format screens, the material picked up from John’s fingers moves at considerable speed; on two slimmer portrait screens on one of the adjacent walls we see the footage taken from his backpack swinging between sky, rock face and the ground where other climbers are holding his belay rope. Finally, in the corner, two small lozenge-shaped screens depict John’s feet as they climb. For the audience, these sources of information serve as ‘toe-holds’ on the experience; watching the 32 minutes of footage, we perform the body connecting the material together and get a greater sense of the height, balance and movement of John’s body and the sheer physical effort necessary for the ascent.

The sense of a shared human experience dominates; John’s occasional groans of physical exertion or gentle expletives are interspersed with careful negotiations between himself and Shipsides as to how he should best proceed. When John enjoys a momentary rest and jokes with Shipsides we too enjoy the feeling of relief and camaraderie as we watch John’s stilled feet and shaking back as he laughs. Reflecting on the experience in a later conversation, both recognize that what is compelling about this work has far less to do with its intended focus on landscape and blindness and more with its exposure of the broader dynamics of climbing as an experience bound up in social interaction; as John puts it, “socializing is what people remember.” This early realization allows Shipsides to adapt his somewhat “mechanistic” initial methodology.

|

| Dan Shipsides: Echo Valley/ A guiding dilemma, installation shot, Gallery 2; courtesy the artist |

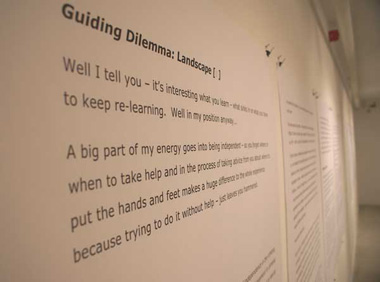

In Gallery 2, A Guiding dilemma is made up of a variety of works: extracts from the transcripts of John and Shipsides’ conversations are mounted on the wall and separated thematically into Landscape texts (the ethnographic interview becomes conversational artwork); two video works integrate some of the audio of the interviews over video sequences and seem to act as visual conversations with John’s words; photographs depict John climbing. There is a constant sense of the overlapping fabric of the material as you move from work to work, sometimes explicit, at other times not, setting up new resonances. While John talks about how blindness affects the retina in the video piece Dolerite, solarized pigmatosis (Dunmore Head), we watch Shipsides’ visual analogies for John’s shifting perceptions of light and his sense of connection to the landscape. Fingertip footage pulses hectically, cutting in and out like interference, and the solarized patina of the images on dual screens creates a sense of the tactile intimacy of John’s engagement with the rockface.

In the single-screen DVD work A Guiding dilemma, the audience is invited to don headphones and more personal, but no less philosophical insights are made available through the artist’s choice of shots. Interview material plays over footage of John, shot from the waist down, making his way down the street guided by guide dog Voss. Shipsides and John discuss the “dilemma” Shipsides experienced when he was not sure whether to verbally assist John in his climb or not. There are moments when conversations and images resonate back and forth between this work and others: for example, the film cuts to footage shot from a car as the group approach the mountains in the Costa Blanca where they will climb, and as the vast rock faces loom into view, John’s comment in one of the transcripts that “ignorance is bliss” comes to mind like an echo. At times, Shipsides’ visual observations are poetic; in one scene, we see what we presume to be John, Shipsides and colleague Gerard in conversation in a café, but the shots are close-ups of their hands negotiating the everyday objects of the interaction: cups, cake and sugar. Between sequences, small cubes of colour appear, suspended mid-screen like meditations on pure light, and one wonders whether the artist is implying that colour fields can also be seen in the mind’s eye.

If, as Hal Foster once rather acerbically argued, some artists are guilty of “ethnographer-envy,” it is refreshing to see a body of work which explores the richness of this cross-disciplinary terrain to such positive effect without the “presumption of ethnographic authority” Foster warns can ensue. [1]

Shipsides’ self-reflexivity and sensitivity come across strongly throughout, as do the patience, generosity and thoughtful engagement of John. The mutual discovery going on throughout the project is clear, with the participants learning from one another. At one point John, who is a physiotherapist, describes the proprioceptors to the artist, the “little sensors in your joints which just allow you to know…where your body is in space.” At another, Shipsides comments that through the process of the work his belief that the other senses are more acute for a blind person has been overturned. Rather, he observes that John made greater use of the sensory data he received, climbing at a higher technical level because he adopted less easy strategies than a sighted person, a phenomenon which John clearly finds interesting to hear.

Gary Tarn’s 2005 film Black sun provides a filmic exploration of the experience of Hugues de Montalembert, an artist blinded during a street attack. Montalembert observes that some sighted people only use their eyes to avoid obstacles, not to try to understand, and that ultimately “vision is a creation.” [2] What we make of what we perceive and the related issue of what vision really constitutes are also raised here. There is a point in the DVD A Guiding dilemma where a small bird, having seen itself in a reflective surface, presumes that there is another bird there and flies repeatedly upwards in an attempt to find it, as though bound by a thread to the potential subterfuges of sight. Here, Shipsides beautifully captures one of the key insights to emerge from the project, the importance of how we respond to the sensory messages we receive. John’s comment on this issue is poignant: “It’s about using the clues you do get – as best you can. It doesn’t mean you have superhuman skills. We’re all the same, we just get more or less clues – it’s about how you use them.” His words have nothing to do with sight, since this clearly does not guarantee vision, throwing the onus back on the audience. How well do we respond to the sensory cues we are given?

Victoria Walters is a PhD student in Ethnology and Folk at the Academy for Irish Cultural Heritages, University of Ulster.

[1] Hal Foster. ‘The artist as ethnographer’, in Marcus, G E and Myers, F R, The Traffic in culture: refiguring art and anthropology, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, pp.302 – 309

[2] De Montalembert, H. in Tarn, G., 2005. Black Sun, [DVD] Pal, London: Passion Pictures