The following is an interview with the artist Gavin Turk before the opening of the group exhibition The Art of Chess at the Sebastian Guinness Gallery in Dublin. The interview covers themes of authorship and authenticity, the subtleties of the use of humour in Turk’s work, and sheds some light on the reaction to the notorious blue plaque at his degree show in the RCA.

CB: As a student of an art college, I’ve always admired your work for your degree show, Cave, where you painted your three walls white and hung a blue heritage plaque on the centre wall to commemorate your own time at the college. Did you anticipate how your tutors would react? (the piece was famously failed)

GT: Nnyye-no, no not really, that was quite a shock actually.

CB: Oh, OK.

GT: I mean, I realised I wasn’t entirely giving the college what they wanted, but y’know for me I was really trying to look at what… Outside of art college – if you gave yourself the suggestion of a successful artistic career – what or where it might take you or y’know, what might be preserved at the end of the day. Y’know if college is itself a kind of vehicle to take you into the future, where would that future be or how could it be manifest? So I think I was just sort of playing around with various possibilities and in a way the degree show seemed to be such a small part of the process, that I was quite, I was quite shocked when they took issue with my final year show and refused to give me a certificate. Umm, the story was more complicated than that though, because then the rector of the college ended up becoming the head of English Heritage who were the people who were in charge of um…

CB: …actually deciding where the real plaques were placed?

GT: Yeah.

CB: So you think maybe a political decision in the end?

GT: It became much more political than I realised, I mean, I think if Joshua Stevens had not been going on to do this job… I think that he personally thought that I’d found out something about him, and I was making a comment about his career, or his life. So I think he took it on quite a paranoid level and thought that I was just making a slight or a jibe towards him personally but I had no idea about it and it wasn’t, there wasn’t in any way any intention towards that. I was very much thinking about South Kensington, the college, of site, of memory. I think also, like, of existence in some sense. Art is a process where you’re able to talk about or think out loud about the process of existence, and I think that, for me, it was a kind of a chance to look at that site – y’know the idea of the site-specific installation?

CB: Yes .

GT: It put me in mind of ‘what about installing the frame’ or the points of reference: something outside of the actual site, to try to then reinforce the site itself. And still to this day I think it was a fair-enough work. I thought when I wasn’t awarded the degree it wasn’t because the piece wasn’t successful, it was because the college didn’t understand the points of reference or the reasons why I had done it.

CB: In terms of success, it’s since more than proved successful, hasn’t it?

GT: Well… I think one of the most interesting things about it was it created a story – it developed the work into a story, which could be communicated relatively directly in story form and could run in parallel to simple art criticism. One of the elements of art which is almost a necessary ingredient is that art can allow or create a kind of space within which you can talk or think things through. I think a lot of art gets made somehow to its own ends, within its own narrative. And I think when I made the work I made it within its own narrative but what happened was that something else took place and then there was this story. So in a away it popularised it in a way that I couldn’t have perceived of.

CB: Stepping back and allowing the piece to develop its own story is in keeping with your examination of authorship, a theme that runs through your work with icons and even your signatures. I read in your 2004 book with David Barrett that you were quite happy for your work to take on a life of its own.

GT: Yeah, I think that as an artist there’s obviously a point where you have to understand the contract is also with the audience – they take up a role within making the artwork work, or making it whole. Art is made within a context that involves the artist and the audience, and it’s a cultural activity – if I was on a desert island I don’t think I would consciously be making art, I’d just be surviving and trying things out and testing things. But if someone else came to the island they might go “Ooh! There’s culture on this island,” but then they would obviously have to interpret it through their own cultural means. But for me art is very much like a dialogue, like a cultural activity, its very much like a kind of language or communication, so it needs that audience. There is a point where I might think sometimes, I make something, and say well my job is to make the thing and then it may be that there are other people that are better at explaining it or maybe that they’re better at seeing what it is that I’ve actually made.

CB: I notice about your work that it references a broad array of things, there are a lot of layers of meaning and symbolism, particularly referring to art. Would you describe yourself as a keen student of the language of art?

GT: I think I’ve always… I spend a lot of time creating frames or trying to look at the things that surround art, the things that actually give art its sense of presence or its sense of importance, or its sense of value. Maybe that also extends to looking at culture and seeing how culture itself values certain things and so if I might use work that involves iconography or even iconic artists I’m sort of using those artists or charging those icons with the sense that ‘how do those statements, or the existence of those things, how do they form markers?’ How do they form highpoints that we then map in a way our mentality? Its almost like retracing your steps: you get born, you grow up and you start to understand the world in a certain way and you take certain things for granted. So it’s about taking the things that you take for granted and then trying to work out at what point was it this was accepted and why? It’s almost like tracing the origins of meanings of things. There’s a sort of etymological sense to the way that I think about art, that I might want to use art to retrace the meanings of things… I suppose? (shrugs laughing)

CB: I noticed the use of humour in your art, in can be quite subtle and varied. Then there’s your use of puns, like Duchamp – relating back to the theme of this show, The Art of Chess, when one thinks of art and chess he’s the one figure who straddles both worlds. There have been a lot of parallels drawn between Duchamp’s and your work. He liked to play games and hoaxes and your piece here The Mechanical Turk is all about an elaborate hoax that was toured around Europe in the early nineteenth century. As for your own use of humour in your work, is humour something you consciously use as a sort of tool for communication or is it something that occurs naturally in your work?

GT: I think its probably something that occurs naturally in my work. I would say for me, that the kind of eureka moments are those where I feel like I’ve managed to join together two probably unjoinable things, I’ve managed to find a way of joining those two things together, hopefully to make a kind of heightened or slightly surrealistic – a super-realistic moment. There is a great sense of enjoyment that I find, and there is a point where it amuses me. I think the word amuse is really important, because its sort of about thinking: it’s the join together between the amusement arcade and the museum, the way that something is preserved for leisure or activity or entertainment and the way that these things can come together. And I think that for me, I don’t consciously want to make a joke. I just want to find the way that people take for granted, or take very seriously, certain elements within art or certain formats for art – that those are taken so seriously I find very amusing because in a lot of ways I don’t fully understand howthey can be, because they are quite undermining. An example you might look at is the signature, one of the crazy things about a signature is that people desperately need a signature on a piece of artwork in order to feel that the artwork is authentic, but the signature itself is like a defacement or graffiti upon the canvas. The best example would be a landscape painting with a signature in the corner: the signature disturbs and fractures the whole space that’s been created – so in a way it’s a contradiction to the idea of making the painting in the first place. It seems to live in this floating space. So sometimes I think: “Well, what happens if you magnify the signature, and you just have the signature so big that it obscures the picture underneath, which is actually what people want!”

CB: Like in you’re 1,234 eggs piece where you signed you’re name by breaking the eggs underneath…

GT: Yes, and some other works I’ve done on the signature… so all you’re doing is you’re just saying that you can see that there are certain goals and you just try and hit those targets, possibly in the wrong order, but by hitting them in the wrong order, you’re starting to make a clarity about what you perceive as those targets, so that in itself becomes enlightening, I think. You can use ridiculous behaviour or self-effacing behaviour or various forms of humour to expose things.

CB: A rupture ?

GT: Yes, in a way I’d like to think humour can expose truths, obviously as you chase a truth it changes and becomes something else, but I think it’s a very important way of looking and thinking. I have three children and I know that the best learning experiences are ones where everyone’s laughing, where everyone’s enjoying themselves. I think that they are the one’s that actually seem to go deepest.

CB: It’s a physical reaction as well as something psychological or emotional…

GT: Absolutely, and it’s a point of connection, a true connection somehow. Almost like, I find, that the most surreally serious moments in my life have often actually made me laugh a little. It’s probably a bit of a bad one to say but, I do remember standing in a pub during a two-minute silence. Moving from the front bar where nobody was observing the silence to the back bar where we were, and then becoming silent for the two minutes, while everyone in the other bar hadn’t realised – and suddenly two minutes was a really long time. I could only feel that we were all doing this really strange and weird thing together and I found it really kind of elating, it made me feel quite amused. By the end of the two minutes it felt like we’d all played some sort of a funky game. But obviously it was two minutes of some sort of shared identity and a moment of incredibly serious human bonding, and obviously my response was… well, I had to be quite careful not to giggle.

CB: It may also be nervous energy…

GT: Yes, it may just be nervous energy, yeah, cos when you get close to something, close to the truth… it tickles.

CB: One final question before we go: given the two motifs in your work of punning and the egg, What came first: the turkey or the egg?

GT: Well… I’m not sure if I can say but, there is a theory that possibly the egg came first because it was a single cell organism, like an amoeba, but I don’t think it is a single cell really, although it’s nice to think of an egg that way. Yeah, I don’t think anything came first!

CB: Well hopefully there going to set us right about that at CERN later today!

GT: Yeah, CERN – what came first, the International Monetary Fund or Steven Hawking?!

Cormac Browne is a visual artist, working and living in Dublin; he has a BA in Archaeology and Italian literature from UCD and is currently in his final year of a BFA in Media at NCAD.

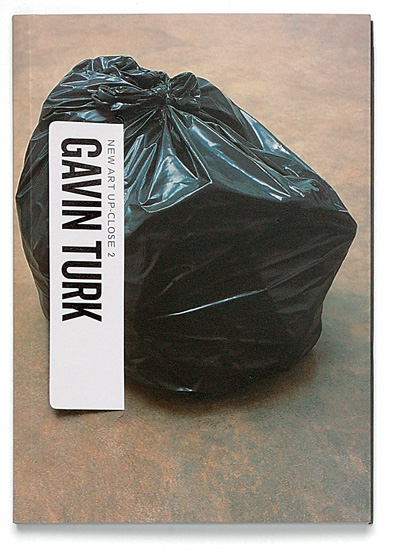

Note: One image from the original article is no longer available.