Colm Desmond’s recent exhibition as part of the summer programme of artist-initiated projects at PCP presents the viewer with a number of formal problems to resolve. It is a difficult body of work not least because the viewer struggles to decipher whether to view the work in the flat plane of two dimensions, or as a sculptural undertaking.

Desmond exhibited a series of five cabinets, along with a photograph which presented a trompe l’oeil view of a studio space, and a curved wall relief. Together, at first glance these recalled more strongly the assemblages of Dada practitioners than post-minimalist practice cited in the press release. I felt as though the arrangement of objects would feel more at home hanging on the walls as they were flat and felt entirely committed to the world of the picture plane.

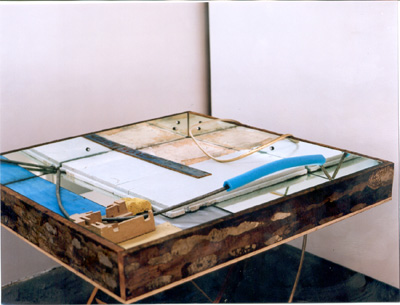

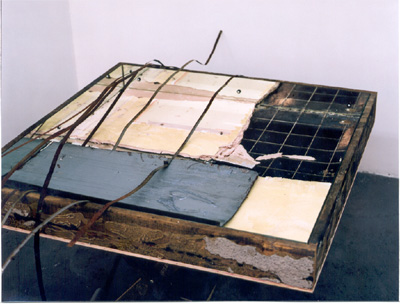

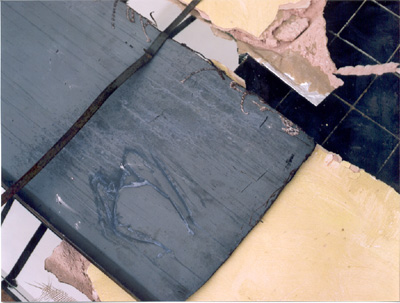

The cabinets are presented like archival displays, the author forming a collection of detritus which looks to be reclaimed from building sites, or industrial activity. The objects placed inside the rough-hewn wooden cabinets ranged from rubber to copper tubing, foam, sponges and linoleum. Occasionally it seemed that pieces had been ripped asunder to expose further layers of material beneath. However chaotic and Dada-like the objects seemed initially, it soon appeared that there was an overriding sense of control and order imposed upon them as they were arranged in carefully considered grid-like patterns.

The grid emerged as the logos of this installation; it faded in and out throughout each individual piece, appearing as a pattern on some linoleum flooring inside the square of the cabinet, then again in the faux randomness of piping overlaid on squares of carpet underlay. In fact the whole installation was the macro of the individual (micro) pieces. The tables were arranged in the gallery as squares, making them like archeological or forensic digs on a former construction site, punctuating the space and demarking it as a picture plane of its own. Rosalind Krauss remarks that the grid is “supposed to manifest to us as viewers: an indisputable zero-ground beyond which there is no further model, or referent, or text…” but she also refers to it as a deception, an artifice that disguises. “The grid thus does not reveal the surface, laying it bare at last; rather it veils it through a repetition.” [1]

So it seems with this work that the viewer is waylaid by the mesh of the grid. Desmond produced a kind of order from material chaos by imposing the grid regime on these throw-away scraps. He imposed his will as artist upon the readymades and the junk in an attempt to ensure that the pieces almost no longer read as what they represented in their former life. For a time, it seems, the original signifiers are subsumed and reworked to serve another agenda – that of the self-referential art work. The capsule-like space of P-C-P facilitates this effect. It is like a hermetically sealed box – removed from the exterior world, creating an other-worldly space where a self-referential artwork just might be possible.

There was a continued duplication taking place in the work; mirrors were strategically placed around the edges of the cabinets so the viewer sees again and again the lines and forms repeated to infinity. The picture plane appears to go on forever, aided by the occasional piece of wire or tubing which appeared to have escaped the confines of the edges of the cabinets. These jut defiantly over the sides or wind their way below to the supports of the structure.

Meanwhile, the wall pieces were like portals into a space where normal conventions of perspective are made absent. When viewing the curved concave wall relief, the presence of the shiny surface created a continuum where one’s own reflected image appeared within the work. Desmond has photographed and effectively flattened objects that once had form, only to render them again into another three-dimensional guise. As I put my head closer and inside the centre of the piece, I realised that my peripheral vision had been engulfed by the object; all I saw was the artwork and myself on repeat, lines and representations of objects playing over and over again.

Overall there was something slightly uneasy about all the works as they grappled with horizontal and vertical planes, the x and y co-ordinates of the grid reappearing ad infintitum in the junk palette. I still have the sense that these pieces are like horizontal assemblages, more truly than they are sculptural. As the title In/elegant formalism suggests, the pieces speak of an attempt to impose formalism on these disparate and once utilitarian objects. Inelegant they are at first, but their true ordered intent prevails.

Barbara Knezevic is an artist based in Dublin

[1] Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant garde, 1981; excerpted in Art in theory 1900 – 2000, ed Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell, 1992, p 1035