The interview with Dublin-based artist Tadhg McGrath began with an enlightening discussion on the baffling question of why the Republic of Ireland, unlike any other other country, including the USA itself, felt the need for a national day of mourning for September 11. Apart from the fact that it was quite an unprecedented and as yet unrepeated phenomenon, it incited a certain amount of outcry – our conversation went – from outraged American companies based in Ireland, fearing for their very precise productivity projections. Apparently, and I will add the obligatory, carte-blanche ‘arguably’, it comes down to a coincidence of dates. September 12 happened to be the fiftieth birthday of our esteemed leader, An Taoiseach, and apparently it had long been a sneaky ambition of his “to give everyone a day-off." Thanks Bertie, I think.

The relevance of this conversation, beyond the preliminary pre-interview idle chit chat, is remote but ‘there’ nonetheless. Firstly, McGrath’s birthday occurs the day after that of the Taoiseach. Were it not for this fact I, nor you, may never have found out the ‘arguable’ truth. Secondly, McGrath’s 23 piosaí beaga“, currently on show in the Irish Film Institute (IFI, formerly IFC), deals with the tenacious taboo of war and conflict, specifically in Northern Ireland (but not exclusively), in a novel way, leading the viewer off the beaten track with regard to the subject matter.

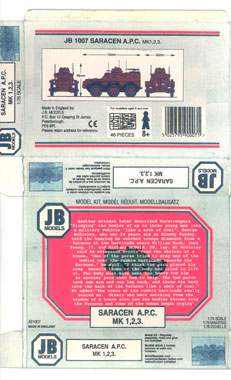

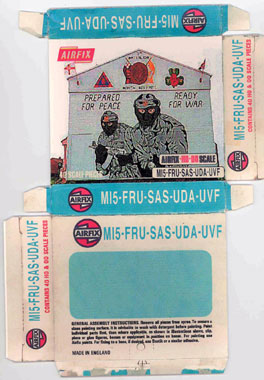

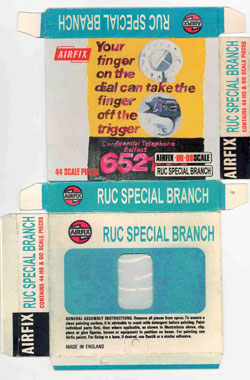

Briefly, McGrath’s exhibition consists of two types of works, which make up the total of twenty-three small pieces. The first consists of a number of fabricated Airfix boxes (a brand of model toys, mostly associated with teenage boys and undeveloped men in their thirty-somethings). The boxes are contrived to look as though they once contained unassembled parts of toy-model IRA / RUC / MI5 tanks and weapons. Some are displayed in three-dimensional format, but for the most part we find them flattened and framed. McGrath also created models of the streets of Belfast, complete with the mundane presence of the military armoured personnel carrier and the absurd presence of toy zebra’s and giraffes. These are presented as modestly scaled and modestly framed photographs.

The venue itself is unusual. The IFI has, over the last few years, undergone a gradual liberation campaign from the yellowing visual clutter that crawled the walls, conveniently leaving space free for someone such as McGrath to approach the IFI and propose an exhibition. McGrath was excited by the venue simply because he was “looking for a place where people actually go." He meant no irony with this statement. Straight to the point, and earnest in his ambitions, McGrath is not merely creating for the art world, nor the typical art buff. He is creating for the world, for the layman. A distinct lack of egotism imbues McGrath’s show and his conversation. You may even have seen McGrath’s show, upstairs in the café area of the IFI, and failed to recognise it as a temporary art exhibition. The show was opened by comedian Brian Murphy (known for his Après Match persona) in the guise of “Professor Gunther Grün (pictured), noted philosopher and art critic from Wüppertal in Germany. Dr. Grün has written widely on politics and art and in his opening speech he shared his innovative ideas on “the art of the romantic in post-structural culture."

McGrath has deliberately avoided an ‘in your face’ presentation of the work. A palatable presentation was key and “every decision to do with the installation was to tone it all down." In 1989, the late Alan Clarke titled a docu-drama about the troubles ‘Elephant’ [ 1]. The idea was that the problems in the North of Ireland were as easy to ignore as an elephant in the living room. Frankly, the case is quite different in the South of Ireland, where we seem to find it all too easy to ignore. McGrath exonerates our reluctance, in the South, in adressing “the Northern Issue," pointing out that the conflict was a subject on which we have previously been actively silenced and censored. RTÉ’s enforcement of Section 31 is a prime example. Our ignorance, our discomfort and consequent insecurities with regard to the North and the Troubles is astutely dealt with and intentionally undermined by McGrath.

One definitive aspiration of the show is to “allow the viewer to think about the conflict with a greater degree of equanimity." In this way McGrath situates the exhibition as “a starting point." And so Photoshop, mounting card, small boxes, mildly amusing photographs and toy animals gently draw us into contemplating the Troubles, trivially (as an integral part of an aesthetic experience) and / or seriously (in terms of personal experience). Thus there is a subtle, even tentative connection between the Airfix toys and the aforementioned insecurity we feel in relation to the conflict. Airfix toys, according to McGrath, fulfil a certain role; making the perfect replica is something young boys can control absolutely, unlike anything else in their pre-adult lives. Likewise one can, to an extent, control a discussion of the conflict if it is approached via art, or culture in general. In fact, as McGrath astutely points out, for the most part, war and political conflict, inclusive of the conflict in Northern Ireland, are initiated into our consciousness by way of fictional sources. Thus our understanding of wars and “difficult events is transmitted through the playful." McGrath’s exhibition is an extension of and a play on this latter assertion, explaining the toy models, model streets and ludicrous wooden animals. It also seems apparent that McGrath intends his art as a corrective to the many other inadequate visual and cultural representations of the conflict in Ireland. “That dreadful film," i.e. The devil’s own, starring Brad Pitt and Harrison Ford, is foremost in McGrath’s mind as an illustration of the latter.

23 small pieces exists within a wider conceptual context than that which we see in its physical form. McGrath states, in a questionnaire which accompanies the show, that the “exhibition is part of a research project into visual and emotional memories of the recent armed conflict in Ireland." As part of the ‘research project’, McGrath asked willing passers-by outside the Houses of Parliament in London in April of last year to read a list of placenames in the six counties. The tangible result was a video piece titled Places in the UK.

McGrath sees his art as being less within the traditional parameters of a craft, whatever its form, and more as an exercise or contribution to creative cultural activity, defining himself as a type of “cultural activity worker or researcher, or both!" It was a slow process of arrival for McGrath, one which freed him from his own pre-conceptions of what an artist and one’s art should be. Having obtained “a painting degree" from St. Martin’s some years ago, McGrath struggled with, for him, the deficient tools of oil paint and paint brush until very recently. Now McGrath is anxious to avoid any stifling prescriptions. Consequently, any discussion of his art in terms of labels and categories is a sensitive issue. He is well aware of the pitfalls of categorising his work as political art: namely that it can easily be demeaned and demoted to the exiled state of propaganda.

In life McGrath is very certain of his political views, but in his art he “is looking for an overview rather than a polarised view." An ambiguous viewpoint has thus been conscientiously maintained, and it would even seem that McGrath, in this show, has constructed a common identity for the various military and paramilitary groups represented. Importantly, the images of the groups originated with the groups themselves, appropriating their propaganda, such as a poster from an RUC recruitment campaign. McGrath aims “to interrupt the ideology," not to advance the ideology, of either side of the divide. In this way it could be said that McGrath’s art is politically concerned as opposed to politically involved.[1]

In order for McGrath’s show to be successful it must stimulate conversation, invoke memories and emotions, and provoke us to “think outside the norms," go beyond a state of merely “re-arranging our pre-conceptions." One question that hovered in my mind, looking at the work and afterwards, was why an armed personnel carrier, a means and powerful symbol of the destruction of life, inhabiting the middle of a residential street, seems so commonplace, and yet a colourful giraffe embodies the notion of absurdity. I think this may be the “ludic quality" that McGrath desires to communicate to us, the viewer; the ‘café-goer’ as well as the ‘gallery-goer’. At what point do we stop seeing (and blindly accept), stop thinking and no longer question?

Claire Flannery is a critic based in Dublin.