|

| Degree Show installation shot, with works by Meaghan Schwelm (floor), Kathleen Gilson (left wall), and Brian Kelly (back wall); photo / courtesy Jim Ricks |

Eleven artists featured in this years graduate MFA show held at the Burren College of Art. The show, Even Odd, was aptly titled, as many varying styles and approaches were represented. Starting off, the instant impact of Brian Kelly’s paintings and Meaghan Schwelm’s floor piece in the main gallery space gave an indication of this.

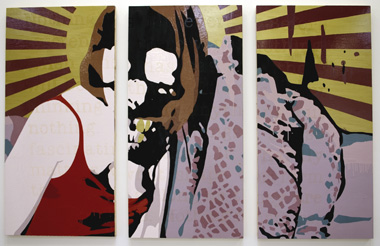

Kelly’s visually arresting painting style demands attention – due simply to its scale and colourful style. One imagines this is the artist’s intent, as the imagery too is deliberately provocative. With titles like I’m hungry for you and Best black tail in town, Kelly takes the superficial aesthetic of sex-industry flyers and advertisements and searches for redemptive qualities, or at least invites the viewer to. The pictoral planes, which are treated in flat areas of acrylic colour, are broken up often into diptychs and triptychs and transgressed with splashes of unidentified substances. The paintings draw a trajectory from raw libidinal energy and desire to mortality.

|

| Brian Kelly: Why is there something rather than nothing, gloss paint, matt paint and varnish on board; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

Schwelm’s floor piece, Scrap, consisted of a very large number of paper cut-outs of nature illustrations. It occupied a large space without dominating it. The balance in her work, between the robust nature of the concept and the fragility of these objects, made it one of the standouts of the show. This quality also came through in her other works on show – a wall drawing made from seeds, Breadth, and multiple small sculptures.

Kathleen Gilson’s series of photographs, Likeness of the unseen, were also quietly inquisitive. The artist focused on everyday scenarios photographed in such a way as to capture a sense of the unreal. In an era where Photoshop and image-manipulation are ubiquitous, her photographs show that the formal concerns of photography are as useful a tool as any computer program.

Marie Connole’s expertly rendered installation of her series of watercolours, Disturbances, was at first glance a benign collection of organic forms explored through colour and composition, but on closer inspection revealed hints of a more personal story.

|

| Marie Connole: My self-inflicted migraines, watercolour on paper; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

The work of another painter in the show, Jackie Knight, also used colour to good effect, yet by contrast her subject matter veered more towards an investigation of human commonality as she explored disembodied facial studies. Of her paintings on show, ranging from enormous canvases to framed studies, the smaller-scale works such as Temper and Exeunt captured an eerie quality and stillness.

|

| Jackie Knight: Echo, latex paint on canvas; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

Loren Erdrich’s showing was a refreshing mix not often seen – woollen work and drawing. Somehow she managed to connect the two successfully. I feel ridiculous, her series of woollen portraits and models, was quiet and captivating. You got the sense that her work could continue in this vein in lots of different ways by straddling the line between representation and embodiment.

|

| Loren Erdrich: I feel ridiculous 1 – 14 (detail), wool and mixed media; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

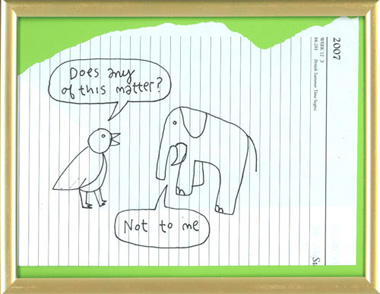

Paul Timoney was one of the artists on show whose work used a variety of media to communicate his message. In doing so he set out to debunk any preconceptions we may have about any and all of them. For example, of the three video pieces on show, each had its own specially fashioned chair, scrapped together from bits and pieces of doors and old furniture, not always entirely comfortable to sit on, it must be noted. In particular, one of these videos, Peters paintbox – on the mountain, a highly entertaining parody of an art-instructional video, was for me the most effective piece. With no clear line drawn as to whether the joke was aimed at the work itself or if, as a viewer, I was part of the joke, it made for a slightly strange experience, which is no bad thing. His attention to all aspects of how we generate meanings, especially in a gallery context, made these pieces what they were. Segregated fruit and fibre, and some of his sculptural pieces, all engaged the absurd with a dry humour which was refreshing.

|

| Paul Timoney: not to me, pen on paper; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

With a similar intent to subvert ideological standpoints, Jim Ricks’ work highlighted issues relating to capitalism and world politics, in particular, those of his native America. His use of a consciously cluttered aesthetic blurs the line between high and low and highlights the limitations of representation and how we as the art audience consume it. Amidst the noisy hyperbole of his installation Imperial war museum and his paintings, his work makes clear, as a concept, the often flimsy opposition art poses to capitalist might and similarly how unsuccessful imperial ideologies represent themselves through the formal conventions of art itself. His works are urgent questions aimed at capitalist and imperial structures. Sculptural installation, painting and video were all used to good effect. Unfortunately, I arrived just as the end credits to Rambo III were rolling, but paintings such as Hand made in Ghana and Baghdad were equally entertaining.

|

| Jim Ricks: War museum, installation detail; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

Dante Cozzi, another American artist, used an entirely different approach. The artist’s standpoint is entirely humanist and is concerned with the connection, or lack thereof, between members of society. His work on show consisted of documentary photographs of his various interventions. These ranged from placing handmade signs in the rural landscape, a timebased portrait project, and a hug-giving service in Galway city. As well as the humanist agenda, all of these seemed to call in the question the role of the artist in today’s society, or indeed the relation of the artwork to the public.

Perhaps in terms of subject matter Gini Tevendale’s work spanned the gap between these two previous artists, drawing on her diverse background and childhood as inspiration to take a peripheral view of art and identity using a combination of photography and sculpture. Her atmospheric lightbox housing a live scorpion was a very interesting piece.

Unfortunately, at the time I visited, Jan Pieter Fokken’s interactive installation Rules of the game, which explored the theme of creation and destruction, had already been taken down. I would be interested to see this artist’s work at a later date, as the documentary evidence was fascinating.

|

| Jan Pieter Fokken: Rules of the game, installation detail with artist; photo Martina Cleary; courtesy the artist |

Ranging from the cluttered to sparse, delicate and calm to punchy and loud, the overall thrust of the show covered almost every angle conceivable. Yet somehow, as a viewer, this avoided being a tiresome exercise in piecing and placing each artist’s work in relation to the next, it was an easy and enjoyable show to digest. This is due to the quality of work on display and also in part to the hanging of the work which, it must be noted, is not always a priority at graduate shows.

Niall Moore is an artist based in Galway.