|

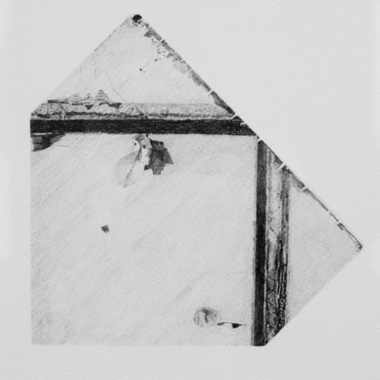

| Brian Fay: Vermeer Crack Drawing: Radiographic layer and cracks c1665-66, 2006, digital print on paper, 40 x 30 cm; courtesy the artist |

While it is tempting to say ‘not another drawing show!’, Brian Fay has shown a continued commitment to drawing that goes beyond its current re-emergence in contemporary art practice. This commitment is displayed in the central role the medium of drawing plays within his practice, and in his co-founding of The Drawing Lab with Siún Hanrahan at DIT.

In this, his first solo show in Dublin at The LAB Gallery, he applies himself to the task of painstakingly tracing and interrogating the crazed surface of canonical paintings, including those of Titian, Da Vinci, Vermeer, Corot, Malevich and Mondrian. His ‘crack drawings’ and prints, which utilise conservators’ radiograph and X-Ray images of paintings as their source material, map the degradation of works on canvas, revealing their fragility and marking the friction of time and environment.

In his dedication to surface Fay’s works resemble an abstract series of cryptic maps that chart the expanding topography of decay in these paintings, inviting close inspection from the viewer and then sending us pacing backwards in a game of hide and seek to discern a shadow of the original paintings’ imagery in the brittle landscape. Interestingly some parallels can be drawn between Fay’s work and that of both Daniel Buren [1] and Andrea Fraser in terms of practices which critique the museum’s framing of the work of art. As Buren has reflected on the deadness of works, once housed collectively in the museum, Fay ponders on encroaching deterioration in a manner that might validate Buren’s claim that art works must be in someway identical in order to co-habit in the gallery space. As original content is obscured and surface revealed, the conservator’s nightmare becomes the subject, inviting questions about the commercial value of these works, while also referencing our own temporality and critiquing museum efforts to maintain works that have long since left the context of their creation. In a sense Fay highlights the ever-evolving meaning of the art object and the expanding chasm between the provenance of its meaning and the provenance of its value as an object. Just as Fraser has satirically employed the workings of the museum [2] to question its seemingly apolitical position as an institution, Fay’s mappings level all these paintings to a surface value through a subversion of the conservator’s tools. In a similar way he harnesses drawing, which has traditionally held a subordinate role to the painted work, allowing the slave to interrogate the master work.

|

| Brian Fay: Mondrian Tableau X-ray drawing, 2007, pencil on paper, 40 x 30 cm; courtesy the artist |

Fay’s adoption of scientific imaging resembles the practice of the German artist Gabriele Leidloff who also employs X-ray and radiograph techniques. As Michael Salcman [3] has observed of Leidloff’s work, the appropriation of a scientific medium, ie the X-ray, imbues the artist’s investigation with the authority of science. However, unlike Leidloff, whose work bestows inanimate objects with a kind of inner life, Fay’s exposure of works of art to X-rays reveals no inner structure or further depth but rather makes visible the fallacy that meaning rests within the art object. His application of the same process to all source material brings to mind further analogies between the practices of art and science, in terms of arriving at new observations or meaning through the repetition of an action or experiment. As Daniel Buren [4] has observed, for the artist to be truly critical of the position of the art object within the modernist project requires continued questioning rather than the proposition of new forms as solutions.

Fay’s choice of canonical works to examine also suggests a logic, tracing the historic relationship between the fields of art and science from the High Renaissance (Da Vinci and Titian) to Modernism (Malevich and Mondrian). Positioning his own employment of scientific imaging within this history of technological drawing aids, Fay examines the evolving preoccupations of art, the historical development of Modern Western vision and the various lenses both physical and ideological applied to this expression of culture. His focus on paintings that span the emergence of perspectival drawing, Vermeer’s use of Camera Obscura and the influences of photography and the moving image on early-twentieth-century works all highlight the sympathetic relationship between art and science as modes of enquiry. There is a particular irony in the observation of the effects of time on the works of Malevich and Mondrian, both of whom addressed the machine age and man’s ordering of nature. As Fay reveals, time and nature have had the last mark, as it were.

|

| Brian Fay: Some time now, 2007, installation shot, The Lab, courtesy the artist |

In one series of prints, Dust and scratches, Buster Keaton one week, he applies this same approach to celluloid film. Its inclusion in the show disturbs the over all continuity a little, but it could be argued that film is a logical ongoing area for enquiry as a time-based medium.

Monica Flynn is a visual artist, writer and arts administrator based in Dublin.

[1] Daniel Buren, ‘The Function of the studio’, October, Fall 1979 [originally in French, 1971; translated by Thomas Repensk]

[2] Fraser’s performance Museum highlights, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989

[3] Michael Salcman, ‘Postmodernism and the art of Gabriele Leidloff’, Columbia University, New York, April 1997; online at www.medialounge.net/lounge/workspace/leidloff/texte/GLms97.html; see also recirca.com online article by Silvia Casini, ‘The enchanting world of Gabriele Leidloff: Imaging the unseen in between science and art ‘.

[4] Daniel Buren, ‘Beware’, first published as ‘Mise en garde’ in Konzeption/Conception, Städisches Museum, Leverkusen, July – August 1969; revised and extended January 1970; translated by Charles Harrison and published in full in Studio international, London, Vol. 179, No. 920, March 1970, pp 100 – 4