Bookish homes in on the artist/ writer dynamic, and whilst this is not at all a new theme, it does explore the particularities of this relationship − broadly speaking, between the visual and language, through the medium of art and the book. Through exploration of the relationship between books and artists, regardless of their approach, it questions systems of knowledge, the public and private realms both art and literature inhibit, politics, the contrasting and complementary characters of art and text, and at its core the inadequacy of expression and communication that both the visual and language possess and the possible bridge they can build when used in unison.

Hans-Peter Feldmann’s Bookshelves greet one on arrival. At first glance, the large-scale, black-and-white photographic work appeals to the eye from a formalist viewpoint; it explored the physical, geometric and tonal characteristics of a home library. Whilst the image works very well on this level, the intimacy of knowing that this is the artist’s own library reminds me of a self-portrait. For many, the literature we choose to display in our homes is a self-crafted reflection of who we wish to be perceived as. The names of the books are for the most part irrelevant to the work, and there is an element of the staged and artifice in the arrangement of the personal artefacts and trinkets; these techniques are equally common to the portrait genre, and Bookshelves straddles between the private enjoyment and public perception of the books we encounter every day.

|

Bookish, Gallery 1 installation shot, left to right : Rainer Ganahl/ Niall de Buitléar/ Hans-Peter Feldmann; courtesy Lewis Glucksman Gallery |

Transitioning to the public life of books, Niall de Buitléar’s Found bookmark project (Boole Library UCC) compiles the remnants of our relationship to past texts through physical reminders. Leaflets, tickets, letters, notes and general paraphernalia, once probably used as markers of a page, now work as markers in the public life of a book. De Buitléar combed the Boole Library, adhering to its Dewey Decimal System, and every artefact he found amongst the closed pages is displayed on two trestle tables with archaeological precision. Closely reading these found bookmarks, we see personal notes, phone numbers, chocolate wrappers, etc, intimate objects that suggest a personal relationship between the person and the remnant and in turn the work becomes an anthropologic display of the history of an intimate object, the book, through human touch.

While de Buitléar focuses on the relationship between the reader and text in a physical, nostalgic way, Rainer Ganahl’s two video works explore the psychological, political, and revolutionary consequences of the life and treatment of a book. Imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism – Lenin between Spiegelgasse 14 and UBS headquarter, Zurich, and V. I. Lenin, Collected Works (Russian edition) 1962, record the artist kicking Vladimir Lenin’s writing through the streets of Zurich (Lenin briefly lived here) and Red Square, Moscow. The ideological and politically controversial, yet influential, nature of these texts is echoed in the controversial, yet thought-provoking, act of kicking a book. The powerful political consequences books can provoke is parodied in the almost abject act of brutally kicking a book. In contrast to censorship-by-burning, the act of degrading a book, a vehicle of knowledge, be that good or bad, is almost barbaric, yet Ganahl’s aggressive act allows us to explore the immense consequences text evokes. The deliberate destruction of books is echoed in Ulises Carrión’s video, A Book, whilst at the same time the transition of knowledge from book to person to society is suggested to be unbalanced.

|

Simon Popper; Borromean/ Sinthome; courtesy Lewis Glucksman Gallery |

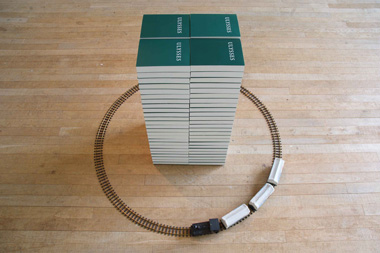

The power of books is embedded in their nature as a vehicle of knowledge and often also as systems of knowledge. Language is in itself a system of knowledge-constraint. Simon Popper questions our organisation of information through the written word in his piece Borromean/ Sinthome . This sculptural work is constructed by stacking copies of James Joyce’s infamous Ulysses in piles, circumnavigated by a child’s train track. However, unbeknownst to the uninformed viewer, these copies of Ulysses have been reordered alphabetically and systematically – therefore using the systematic core of written language, the alphabet, to make any comprehension of the text null and void. The work is informed by Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory of Joyce’s unique method and style of writing. The title, Borromean/ Sinthome, is derived from this theory, which works on the principle of intersecting circles of knowledge, yet for many his concept is seen as incomprehensible because our knowledge of texts is based on codes. Just as Ulysses is made nonsensical by reducing it to its root code, the alphabet, Lacan’s theory is impenetrable without the basic code that informs his philosophy.

|

Bookish, Gallery 2 installation shot, left to right : Jamie Shovlin/ Damien Roach/ Jonthan Callan; courtesy Lewis Glucksman Gallery |

The knowledge available in books is coded to a certain cultural point, and books play a large part in socialisation. Yet books and language often have an unconscious effect on how we see, in a visceral sense. For example, Jamie Shovlin’s piece, named after the book it explores, Ways of seeing by John Berger, physically hides what we see in this book. Berger’s seminal text, which many know as a core university text book, was used until recently almost like a doctrine of how to approach art pieces, and on a larger scale Art History is littered with examples of texts that formed the way we view the visual arts. Yet taking a second-hand copy of Ways of seeing, Shovlin has decided to mask out all previously highlighted or annotated text or image and mount the results page by page to create a formal arrangement that radically changes the meaning Ways of seeing has in relation to this text. Seeing is no longer measured by the content in term of language but instead by the formal visual quality of the book.

As one of many instruments of so-called measuring our world, and staying with the idea that language calibrates the world around us, Damien Roach places books next to rulers and an atlas in Abundant velocity. Marte Johnslien’s Le Livre sur le livre [‘the book on the book’], attacks language as a system of knowledge by referencing Paul Otlet’s research. The title is adapted from Otlet’s 1934 book Traité de documentation, le livre sur le livre, in which Otlet points out the inadequacy of the book as a system of knowledge and suggests alternative methods of knowledge-distribution. Many cite Otlet as the forefather of the internet, and it is not surprising that Johnslien’s installation consists of three parts: wall text, a book, and a website.

|

John Latham: Britannica, installation shot, Sisk Gallery; courtesy Lewis Glucksman Gallery |

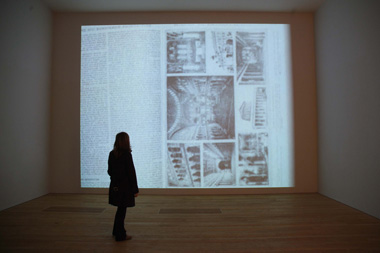

The conception of the book as the seat of all knowledge is intrinsically associated with Encyclopedia Britannica in western culture, and John Latham’s work Britannica, which features every page of the encyclopedia accelerated into a six-minute film, also explores the relationship between the book and technological advances like the internet. Does the speed at which we access information on the internet supersede the traditional method of hard-copy book research, and does it threaten the book’s place as what the Encyclopedia Britannica once claimed itself to be, “the sum of all human knowledge.”

As Paval Büchler and Idris Khan illustrate, the ‘sum of all knowledge’ is open to interpretation, and both artists’ work involves direct reference to seminal writers. Within the theme of reference and the transference of information, Büchler illustrates how information transmitted can evolve in to a game of Chinese whispers. Text citation, notation, influence, and inspiration from previous authors, create a chain in which many authors and books are interlinked. The text of Büchler’s installation is a sum of all the Franz Kafka quotations found in Giles Deleuze and Felix Guttari’s book Kafka: towards a minor literature (1975). Therefore, his work is a quote of a quote which coincidently reads very poetically, and aesthetically the piece printed on a southwest-facing window is beautiful. Again working with literary reference, Idris Khan’s The Uncanny is a blended version of all the pages of this book into one image, becoming in itself uncanny as it retains its resemblance to a book but becomes something visually new, familiar, yet strange.

George Harry Longly’s works, Supporting column #1 and # 2, manipulate images of technical photography books, and through their manipulation, become something new and surreal.

Moving from references of other authors to footnotes, additional information in text, Rosalind Nashashibibi’s film uses visual images in place of the extra textual information. In this work we discover that these visual footnotes are very much informed by the books of our culture and the story that the frog may be the prince in disguise. Yet, the conception of text is very much culturally informed: Katharina Jahnke’s illustrations, based on different covers of War of the worlds, demonstrate how the story of alien invasion is visually interpreted very differently from culture to culture.

Book covers, the visual outer appearance of any publication are the inspiration behind the following artists’ works. In the footsteps of R B Kitaj’s work In our time, Goshka Macuga too collects and exhibits books that appeal to her formal sense of design and make reference to contemporary culture, in After In our time by Kitaj. Jonathan Monk’s works consist of second-hand books on which he used his own CD collection as the material for a stenciled motif exploring the intimate and anonymous nature of second-hand books. Jamie Shovlin, through a series of reworking 1970s paperback books, is able to develop a colour chart that could plot designs for books never realized; the work links visual effects to conveying the type of writer. Peter Wüthrich uses the book cover as a solely formal visual medium, in a direct, yet simple work, Imago . Using the book cover as a base for a three-dimensional montage, Dirk Stewen’s Untitled employs an old hardback book as the base of his work, layering a photograph of a young man taken by the artist, thread, and ink and paper. The whole piece explores the relationship among the disparate elements in the binding process through the use of divergent found objects, and we see the book being used as a material to create a separate art object.

The sculptural possibilities of the book as building blocks of construction are hinted at in Richard Wentworth’s The Red words (Die roten Worte), where we see a red book stuffed with various paraphernalia become a sculptural object through the relationship of the materials to one another. Whereas in Jonathan Callan’s Library of past choices the book unmistakably morphs into a sculpture, using the book as his medium, and retaining the organising principle of the book, Wentworth uses the placement of books like page markers to create a sculptural library, a configuration of books that appears fluid and free-flowing, yet they are still inextricably governed by an organisational system and their relationship to one another.

So far the pieces I have written about use the medium of visual arts to explore the book; however, the ability of the book to explore art is also a huge part of the artist/ writer dynamic and the last section of the exhibition was a selection of books written by artists, both obscure and well known, that have impacted on the way we envision how art should be. At its core, books and art function to communicate; what they communicate is debatable and not always comprehensible − however, that is not necessarily important. Language, and therefore text, by its nature defines, so text can be seen as more definitive; yet, by this nature it is also severely limited in what it can express. Art on the other hand does not share the definite organisation structure language possesses.

The history of artist-writers is not just incidental; books allow them to communicate and express something their art cannot alone, and pari passu their art expresses something literature would fall short of. In the end, what we see and hear are the formative factors in the world around us; they create our reality. Many postmodernist theorists have argued that language creates the world we see and, as this exhibition has demonstrated, the book, as a vehicle of knowledge, possesses immense power. Yet in this exhibition the visual prevails, and it is the visual’s reaction to language that dominates.

Gemma Carroll is studying for her masters in modern and contemporary art at UCC.