|

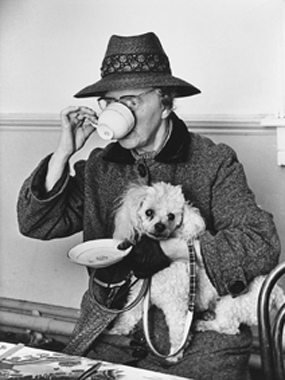

Bill Doyle, Jameson Distillery, May Lane, Dublin, 1963; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

“A retrospective exhibition by a master photographer" [1] is the subtitle given to the exhibtion of work by Irish photographer Bill Doyle in the Gallery of Photography. The exhibition displays Doyle’s lust for capturing the moment, evoking the quintessential notion of a great photograph resulting from being in the right place at the right time, often with a degree of luck. Much is made about the printing of the images by Hetty Walsh, who has been printing for Doyle for the last twelve years. The prints are stunning and are expertly executed. Walsh is a master printer and the exhibition’s emphasis on this skill is valid, as the printing contributes greatly to the show.

|

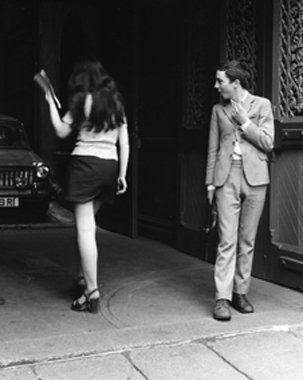

Bill Doyle, Anglesea Street, Dublin, 1978; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

Doyle’s approach subtly veers towards the quirky side, with certain images being reminiscent of the early masters, particularly Cartier-Bresson, whose name has often been used when comparing Doyle’s work. In all there are seventy-three black-and-white images on show, depicting scenes from Doyle’s native Dublin and the west of Ireland. The image titles are simple, giving basic information such as place, location and year (eg, Mansion House, Dublin, 1970 ) and every wall possible is occupied in this exhibition. The images, silver gelatin prints, are either gold or sepia-toned and tastefully framed.

There are two ways to approach Bill Doyle’s Ireland; viewed with a romantic vision in mind, the retrospective will be appealing; viewed without, the result is alltogether different. I fell into the latter category; as a result each image carried with it a dual reading.

|

Bill Doyle, Mansion House, Dublin, 1970; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

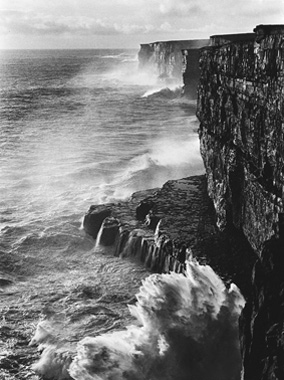

The exhibition is laden with clichés, and they are apparent both in the exhibition as a whole and in the individual images themselves. The images of the west coast of Ireland are where these clichés are most apparent: the rough hands of a fisherman, thatchers up ladders with bundles of straw, toothless women with their sunken faces laughing as they meet on a small village street – further descriptions are not neccessary as the images are so ingrained in our psyche that we can fill in the rest. If one buys into the romanticism and nostalgia, then you will see an Ireland that no longer exists and one for which this exhibition mourns. The tourist favorites of a (seemingly) idyllic Ireland are on display; the classic old-man-with-a-pint-of-Guinness routine is used more than once, and the approach is one of romanticism (ie, don’t mention the money that was so often squandered away by alcoholic fathers).

This romantic take is further heightened by the use of black and white and the connotations that are associated with it. The images work formally; they are expertly taken, are well composed and are technically faultless. Doyle’s Dublin is approached like Robert Doisneau’s Paris and both use a degree of playfulness to give a selective impression of the city from whence they came. But there are too many images on display (it was Doyle himself who selected the images to be shown); this results in an exhibition that is a little too dense and often, particularly in relation to the images of Inis Meáin and Inis Oírr, overly repetitive.

|

Bill Doyle, Dunfanaghy, Co. Donegal 1970’s; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

Doyle weaves myths, of the sort Roland Barthes loved to dismantle. A deconstruction of two of Doyle’s images, Dunfanaghy, Co. Donegal, 1970’s and Máirtín Folan and Páraic Choilí Pheadaí Ó Conghaile, Inis Oírr presented below attempts an analysis of this myth-generation. Looking first at the Dunfanaghy image:

| Signifier | Signified |

| Black and white | Old; timeless / unchanging |

| Sole figure | Alone; isolation; solitude |

| Road | (tracks) presence of vehicles; usage (weeds): not used for some time; remote |

| Dogs | Loyalty; companionship; working dogs – sheep |

| Hill in background | Romanticism à la Paul Henry |

| Weather | Nice day; dry track marks (little rain) |

| Trousers (rolled up) | Ill-fitting: practicality; poverty |

| Satchel | Going to work; old and worn: practicality; poverty |

| Cap | Tradition |

| Stick | Working with livestock |

| Man (back to us) | Not posed / natural: not vain |

| Walking | Lack of wealth; necessity; healthy lifestyle |

| Wrinkles / sagging skin | Older man; hard life; bachelors of the west |

| Grass / gorse at road side | Poor land |

The lone figure in the landscape is presented to us an ideal of the hardworking and head-strong man of the west, the sort of character who just gets on with it. The landscape is wild but not uninhabitated and the basic needs of these people are reflected here. The image lacks any sort of vanity on the part of the subject and the gaze of the dog as he looks up to his master hints at the strength of this man’s character. The putative poverty of this man is reflected in this image through many of the signs, but the image also shows a subject who is not concerned with that. So how would this ‘myth’ read?: Although isolated, solace is found between man and nature. Such men’s needs are simple and their rewards are not found through material gain but rather through their relationship with the land and their closeness with animals. They keep to simpler, older ways; they are tough and get on with it.

Referring to Barthes once more, the studium [2] of the image is clear but it lacks the punctum [3]. This was the case with many of the images in the exhibition; through absence, the importance of the punctum within an image was further emphasised.

|

Bill Doyle, Máirtín Folan and Páraic Choilí Pheadaí Ó Conghaile, Inis Oírr; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

Máirtín Folan and Páraic Ó Conghaile again presents us with a myth to decode. The image consists of few elements: three men (one hidden almost entirely from view), a dog, a boat, the sand and the sea. The day is clear. The breaking waves tell us that the sea is not entirley calm, there is a slight wind, picked up by the sea, the men’s trousers and the dog’s fur. The boat is basic, the men’s clothes too are merely functional, leading us to believe that they are not well off. There is a camaraderie present along-side the ‘typical’ west of Ireland signifiers of the currach and the Atlantic. The myth? It might boil down to something like: these brave, simple men, comrades-in-arms, are ready to take on the Atlantic Ocean. The image conjures up the iconic (and nostalgic) images presented to us by Robert J Flaherty’s Man of Aran which was made some forty years previous to Doyle’s photographs and was itself deliberately ‘aged’ backward by another 100 years or so.

|

Bill Doyle, An Sunda Caoch (The Blind Sound), Dún Aonghus, Inis Mór; courtesy the Gallery of Photography |

Whilst different in aesthetic, Doyle’s images have much in common with John Hinde postcards. But there is also a voyeuristic take on the unfortunate and impoverished in Doyle’s work that made for uncomfortable viewing. Supporting documentation claims that “his work has a lightness of touch, a warmth and humour," [4] but, rather than endearing the images to me, these qualities grated as subject matter and approach appeared to conflict.

Bill Doyle’s Ireland is truly that, it is his Ireland that is represented, it is his myth. I have no doubt that the retrospective will be a success, and for those who view it with a romantic eye the attraction of the images will be great. I can admire the prints for their formal qualities, but the exhibtion was too clichéd, too outdated and too illusive for it to have any convincing impact.

Laura McGovern is a photographer practising in Dublin.

1 Exhibition Catalogue

2 The studium of the image comes from Barthes understanding of it as the Latin word of ‘study’. The studium of the image is the understanding of an image according to its “application to a thing, taste for someone, a kind of general, enthusiastic commitmentÉ but without special acuity". Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Vintage, 2000

3 Barthes found that the punctum of the image would be a “second element which will disturb the studium “, “A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)." Therefore the punctum is not the focus of the photograph but it is that element that stands out for the viewer, as Barthes claims it, it is the element that is the difference between loving and merely liking an image. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Vintage, 2000

Bernd Weisbrod’s images of the west of Ireland, in contrast, often present us with the punctum of the image. ( www.bernd-weisbrod.de )

4 http://www.galleryofphotography.ie/exhibitions/doyle.html accessed on 11/12/07