|

| Bernie Masterson: Broken mist, oil on panel, 76cm x 76cm, 2004; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |

When I visited Bernie Masterson’s studio I noticed a fine portrait of her mother that hangs in the hallway of the house. She told me that doing this kind of work, though she can do it, was not really interesting to her. Portraits are something she does for family reasons. This is worth thinking about, not least because the distinction it draws between the public and the private is actually the reverse of what used to pertain in the art world.

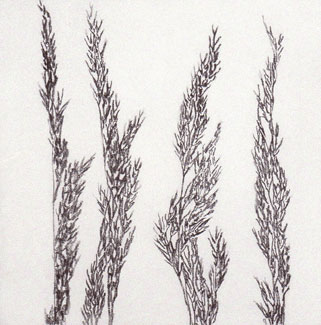

|

| Bernie Masterson: Wild grasses, ol on panel, 36cm x 36cm, 2004; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |

Looking at the question historically, we can say that it was only from the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries that the inwardness of the artist began to dominate. At that time and until quite recently the depiction of other people, the recording of their appearance, was, along with the illustration of religious and mythical stories, the central field of activity for artists. It may be said that portraiture faded in the face of the invention of photography, just as myth darkened before the advance of the Enlightenment, but this is by no means the whole of the truth.

|

| Bernie Masterson: Night falling (Diptych, detail), oil on canvas, 244 x 305 cm, 2004; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |

Actually, it is, I think, more true to say that art created, or perhaps recognised and followed, a turning away by the culture at large from the truth of appearance, which is public, towards the truths of unpeopled landscape and of the individual psyche, which are private. When one looks at Masterson’s work, one is immediately aware that this is nature done over from a personality – nature seen, as it were, from the inside of the artist. And yet, paradoxically, this is true despite the fact that what we see is true to the outside, to the feel, of appearance. These paintings are recogniseably of the Dublin mountains. The glaciated curves, the grey light-filled skies, the heather, the bogs, the fronds of tussocky grass – these are all recognisable and accurately represented. Even more so are the drawings of undergrowth and of, say, the leaves of a hosta plant, curling to dryness and decay. Most recogniseable of all, particularly when we consider the title, is the large diptych called Night falling (which is to go on permanent display in the offices of Fingal County Council). And yet, about Night falling and about the other works in the exhibition it can be said that nothing in them is recognisably real in the photographic sense.

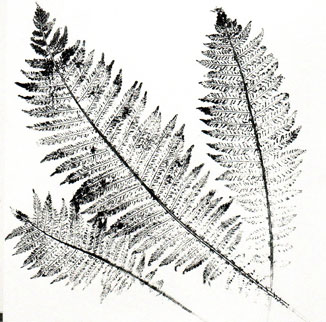

|

| Bernie Masterson: Shuttlecock fern, graphite on panel, 36 x 36cm, 2004; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |

Why is this? To that question there are at least two answers, two answers so intimately related that they reduce to one answer. Primarily, of course, the explanation is that we, the viewers, don’t ever not know we are looking at painting. The first thing the painting says is that it is painting, pure and simple. The second answer has to do, oddly enough, with portraiture, which is where I began. What we have here, by way of fidelity to the twin sisters of paint and nature, is a self-portrait of the artist as a young woman. This is revealing work – one might almost say that it involves a study of the nude. Painting of this sort always involves a great deal of nakedness, of baring the soul to the public. Nothing is private here. The paint is nature and the nature is a representation of personality. Other artists have worked landscape in this way – Tony O’Malley and Sean MacSweeney for instance – but the number of women artists who have done so in recent years is, perhaps significantly, high: Gwen O’Dowd, Veronica Bolay, the earlier Cecily Brennan, Jacinta Feeney, Mary Lohan, Bernie Masterson herself and many others. Why this should be so – what the style reveals and what it hides – remains to be discerned, if it is discernible, and evaluated as a patterning, if there is such a pattern, of the female mark.

|

| Bernie Masterson: Wind swept mountain heather, oil on panel, 76 x 76cm, 2004; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |

Brian Lynch is the editor of Tony O’Malley, published by New Ireland Press, and a member of Aosdána.

|

| Bernie Masterson: Morning sunshine on mountain and tree “, oil on panel, 76 x 76cm; courtesy Draíocht Arts Centre |