“Today, Western imperialism is the imperialism of relativism, of the ‘it all depends on your point of view’; it’s the eye-rolling or the wounded indignation at anyone who’s stupid, primitive or presumptuous enough to still believe in something, to affirm anything at all."

This quote, at the start of an article by Mark Fisher in the current Frieze, reminded me of a book [1] I was reading over Christmas. The quote is a translation from a French, France-related anonymous manifesto from 2005. [2] The manifesto states shortly afterwards: “No critique is too radical among postmodernist thinkers, as long as it maintains this total absence of certitude." The manifesto is a bit of a head-spinner to read, but it’s gutsy. The reason why I picked up on it was because the book I was reading was about scientists’ unproven beliefs; a typical example would be that there is life on other planets, but there’s also a lot of psychological science in the book, and the scientists contributing are of top quality. [3]

It got me thinking about what beliefs I have in relation to art. Do I have anything that strong in relation to art, are they justified, are they useful? Are there any beliefs that I have are stable, that I wouldn’t change over time?

I thought I would start noting down a few possible ones. I wondered if it would be folly to blog them. And I wondered where I’d start. Here’s one: I believe, but obviously cannot prove, that aesthetic relativism is a sham. I’m using the term here loosely to refer to a refusal to make judgments about art. I myself refuse to make such judgments all the time; I’m not sure that it would be good to have an editor going around making imperious art/ not art decisions, though it might be refreshing.

Aesthetic relativism (as I’m using the term here) is also extremely trendy, and I don’t know how we would get around it without. Somehow we have developed an insistence on hedging our bets when making artistic/ aesthetic judgments, while still writing about or curating shows that depend on such judgments for their existence.

As thought-experiment, imagine a conversation with a curator that goes something like: “You picked these artists because their work is good?" “I believe so." “So there’s good and bad art?" “It’s not that simple – it depends on the context." “So there’s some sort of art-plus-context combo that’s good in some absolute sense?" “Well, no, it depends on the context."

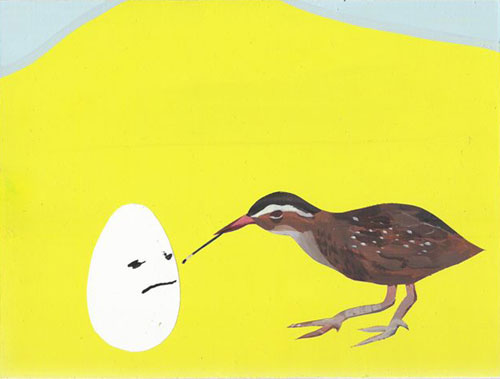

This all somehow reminds me of my attempt to visit the Royal Art Lodge show in the Douglas Hyde Gallery a few years ago. In the entryway to the main downstairs space were hung a few of the smallish works. By the time I had got to the last of these I had to leave – I have some physical aversion to art that is only irony. I suppose I think (believe) it’s cowardly, but the aversion was so visceral that it may go beyond simple belief. In the end, I believe the way out of the aesthetic-relativism impasse may come from a better understanding of the mind; problem is, we may not like the implications of that understanding; ignoring the problem in the face of the solution might turn out to be the best for art (ironically).