A video shown on a small monitor, so that the forearm ‘burned’ repeatedly by nettle leaves is life-size, is hung diagonally opposite the same forearm being ‘treated’ by dock leaves. Nettle Sting does not quite face and is not immediately challenged by Dock Leaf Cure. This folk remedy is one of several Anne Quail learned about from her relatives and friends. Hand-written remedies are represented by one sentence describing a belief that became a theme for the installation; scribbled on the wall adjacent to the entrance the sentence has an aura of unquestioned truth. Like many other contemporary artists, Quail thinks of written texts as “drawings in their own rights” (from artist’s handout). Her use of a particular handwriting is meaningful: slightly too open, shaky, ascending and descending arbitrarily, it is large enough to dominate the wall and call attention to the insecurity of the marks on and of the narrative meaning, a belief.

The two stages of the skin, blistered and cooled, could have been drawings. A preference for video could be the result of a desire for a documentary kind of evidence. Quail states her intention to “have that same sense of directness and unquestioning with the material and how it is presented” as those who gave her the stories. However, drawing is also capable of transmitting those desirable qualities. The preference for video must have been governed by something else, possibly fashion, or perceived contemporaneity of the medium. Video is a newer medium than drawing and may, albeit falsely, forge a perception that the lens-based work of art is more up to date, of its own time. As a remnant of Modernism’s intoxication with ‘the new’, this aesthetic survived the onslaught of post-modernists’ quotations and citation with impressive ease. Intentional fallacy notwithstanding, the video appears to have a direct link to a presence, to the ‘now’ of the concept, whereas a drawing habitually evokes the sense of its longer history, its links to the previous aesthetic norms. I think here of Roman Jakobson’s idea of “collective ideology” – even though not every individual artist or viewer may be able to take advantage of that dynamic system of signs serving a specific aesthetic purpose. The apparent contradiction in Quail’s judging writing as drawing, and her preference for video, subverts the above concern with the physicality of the chosen norm, but does not remove the difficulty with art as (material) object. Since this exhibition is about beliefs, therefore ideas, and opens towards poetry, visual poetry, its art becomes capable of escaping both intention and conscious mind. The tool – as the following will illustrate – is Quail’s clever (if unintentional) forging of optical illusion via a choice of material.

On the back wall there was an exactly measured row of identical inflated balloons, a green dock leaf in each. The light transformed the plastic material into believable – yet untrue – glass. I knew they were made of plastic, but I saw shiny glass! This visual illusion was an outcome – I guess without planning – of a natural law of optics. Just yesterday, walking after a rain in strong late-afternoon sunshine, on one pine-tree branch was a deeply red flame, disappearing after I moved towards it. The light bent in the drops of water so that from a whole spectrum I saw the red colour only, and only from one position. It may appear a negligible point, if I had not remembered oblique (not cylindrical) anamorphism, its unconventionality capable of bringing disbelief into palpable appearance from an appropriate and unique point of view. I am not suggesting that Quail consciously planned anamorphic art, I am proposing though that the appearance of plastic as glass in relation to a viewing point is a kind of anamorphism. Moreover, the link is not that archaic.

I have seen work of contemporary artists presenting anamorphism as a theme, consciously.

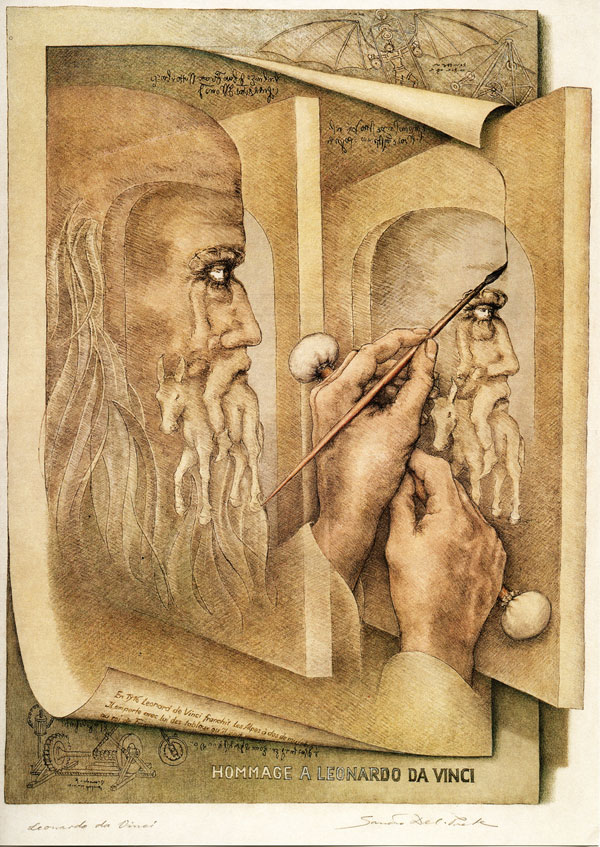

Several contemporary artists explore the validity of methods of visual transformation based on natural laws, not only the laws of optics. Shigeo Fukuda (1932 – 2009) assembled forks, knives and spoons so that they cast a shadow of a motorcycle. Sandro Del-Prete (1937) composed a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci drawing his self-portrait, both embodying the image of a horse rider oscillating with the profile of a man’s head. His sort of limping tessellation posits his images very near M C Escher (1898 – 1972). Octavio Ocampo (1943) layers motives over and over in Amistad de Don Quijote (Friendship of Don Quijote), Istvan Orosz (1951) enhances optical illusions in his portraying of his own space in The Ship of Fools II.

The optical laws are joining the natural laws of replication and mutation of an older meme, the anamorphic image. Quail harvests the meme in an installation grounded in sameness of materials, natural leaves and inflatable plastic with added light, quite unexpectedly.

I mentioned poetry above. The poetic charge of the row of containers does not work in all light conditions, or from all points of view. Is it worth registering? Yes, it is precisely the point Rene Wellek made in 1942 about a poem: “A poem is not an individual experience or a sum of experiences, but only a potential cause of experiences…” (Theory of Literature: 150). That is, after all, a human condition exhibited in every act of cognition or belief.

Almost in the middle of the room, Quail placed ‘grapes’ of balloons rising from the floor, with more forming a wreath or a crown above on the ceiling. Single leaves of nettles hung down like precious smaragds (emeralds). The resulting sculpture perceptibly slowly and gently responded to the airflow in the room, generated by walking visitors. It was not a hanging mobile and it was not about technical issues. While its beauty won me over, I felt ‘locked out’ of its meaning. Only when browsing through other artists’ use of suspended spheres did Quail’s installation grow into a portrait – of a belief, of healing, and of an idea quite central to art, that is, art’s strong relationship with natural forms and laws. Above, I mentioned the laws of optics as a force to create a belief. The systematic symmetry of each object having a leaf attached (real or ascribed) works as a visual metaphor for healing (a little touch of the so-called theory of signature). It also supports a notion of value distributed amongst oral tradition, belief, art and natural force, all connected by people knowing something. Allowing for individual differences does not sanction full-blown relativism. The limits are given by those norms, mentioned earlier in relation to drawing, those that determine how to make an idea visible. I mention here just one tradition.

The idea of art harvesting the transformational morphing faculties of natural forms and laws is not new, while still not exhausted. During the sixteenth century, a century of conflict, an older, classical belief that art imitates nature had been revived by artists and theoreticians alike. The Mannerist painters and sculptors preferred arbitrary proportions and an environment that was not immediately comprehensible. Both qualities are still attractive to modern painting, drawing, and even sculpture.

Philip Haas (b. 1954) has re-exhibited in London recently a fifteen-foot-tall sculpture made of bark, branches, twigs, moss, fungi, vines and ivy titled Winter after Arcimboldo (2010).

In his paintings Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527 – 1597) carefully matched the character of his subject with selected fruits and plants, tessellating them into the convincing anatomy of a portrait. Haas followed that concept while making three-dimensional variations of Arcimboldo’s Four Seasons, whose Winter (1573) contains tree roots whereas the Spring (1573) is composed of flowers and plants. I propose that Anne Quail shares with Mannerists and with Haas a dedicated interest in the relation between people and nature and that she aims at a portrait of one specific relationship, healing.

How does she make that visible?

By the comparison of the skin irritated by nettles and the soothing effect of the dock weed Quail raises more questions than answers. Is the optical difference real or manipulated? If discernible, is the difference a proof of that belief? The visually accessible evidence is not convincing, it keeps the belief as a belief, in the cloud of maybe. I perceive it as a portrait of the uncertainty about a belief held unquestioningly, even recklessly, yet with gentle sympathy. Therefore it is just a proposition to be examined, questioned and either supported or refuted. Hung on two opposite walls, in different distances from a corner that is the ground for the rest of the installation, the two videos create a vortex, a kind of a clench. The composition thus moves the idea from the level of possible to the stage of something held with some force and firmly. Visibly there are two speeds, two stages of being and of transformation. The slow movable twins of bundles of balloons under another bundle as a kind of suspended crown or a wreath offer an entry into a mystery of initiation. A soft breeze-like breath caresses the spheres in their perfect equal sizes, in their perfect caring for the plants they hold inside. I recollect similarly nurturing spheres caressing human bodies in The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490 – 1510) by Hieronymus Bosch (1450 – 1516). The thought of secret connections and / or links to older beliefs and alchemy evolves as no surprise.

The last part of the installation is static, decisive, confidently morphing plastic into the shine of glass globes, tools alchemists used for their experiments. It evokes also a clinically precise laboratory, or pharmacy. The fast march of the sameness from one end of the wall to the other insists on stability, certainty, and success. These qualities are visible as a result of that transformation which is in truth an optical illusion. It works from one point of view only under a particular light. When I move nearer, the optical illusion disappears, and I see mundane plastic and slightly wilted leaves.

What of the decay inside the pristine containers? At an early exhibition at Vassivière (then just whitewashed stables, now a posh art centre) I saw Senza Titolo, 1968, by Giovanni Anselmo, who called it also “an eating sculpture.” A block of granite was attached to a large plinth by a wire holding a head of lettuce. As the vegetable wilted during the heat of the day, the wire loop lost its grip and let the granite fall. The sculpture had to be ‘fed’ with a fresh head of lettuce every morning.

Quail’s use of leaves was less a part of the construction, more the necessary evidence / illustration of beliefs. The whole of her beautifully gentle installation became a portrait of possible healing and its conditions.