Anne Hendrick’s work presents a colourful, enchanted world which is both amusing and strange. Pyramids of coloured dots tower in the sky and knotted trees slink across the landscape. Golden forests and rainbows create a playful, light-hearted feel to the show; however, there seems to be something sinister lurking beneath this surface. Hendrick presents the viewer with locations that are imaginary, but, she then seems to re-interpret these fabrications with memories, creating something else.

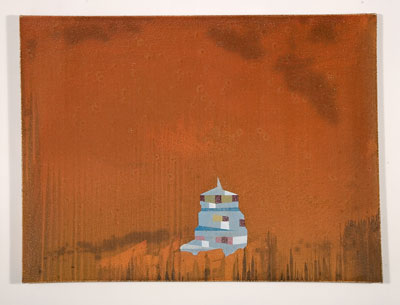

The first painting I encounter in the gallery is Brimstone and fire. The surface is rough, almost stony. The canvas is sulphuric in colour and looks faded or worn away. On the bottom right of the image, there is a strange geometric shape that resembles a building. It seems out of place – the soft pink, blue, gray and ochre shapes look like paper cut-outs. They are flat, smooth abstract shapes and create a contrast. Fire and brimstone are, of course, associated with a god’s wrath and subsequent cleansing and purification of evil. [1]

Bigfoot Country (after Roger Patterson) is a large oil painting depicting a river and trees with a silhouette of an animal-like, dark figure that moves across the landscape. I imagine I can hear birds, startled, wings fluttering overhead and a cricket’s rythmical chirping suddenly silenced. The figure seems to be caught mid-stride – anonymous. This piece resembles the famous video still of a Sasquatch, taken from a film that was shot by Roger Patterson in 1967. The place of the sighting is called Bluff Creek. Thought to be a trick, Patterson was adament that it wasn’t. [2] Hendrick sets up the painting in a compositionally conventional way. The traditional detail is removed, and shapes are reduced to colour and line. The trees behind the river lack detail – they are whited out. The rapid flow of the river is reduced to different shades of blue from light to dark. Just like the video footage of Bigfoot, this painting is blurry, almost pixellated. Although we are aware of movement, or potential for movement rather, the viewer must gaze at the stillness.

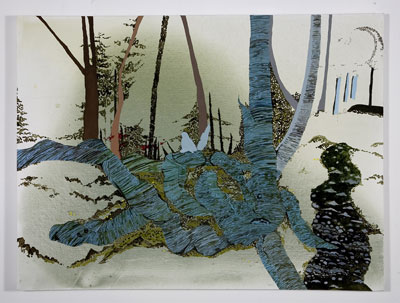

Bluff creek is taken from the same location. The long, thin trees reach up and out of sight. They are strangely pink and purple and blue in colour; the background is flat and green. One tree stands out; it is broader – covered in horizontal lines and blue. The tree twists and knots itself in and out of the ground in an unnerving manner. The work seems unfinished – details are missing, some of the canvas is left empty.

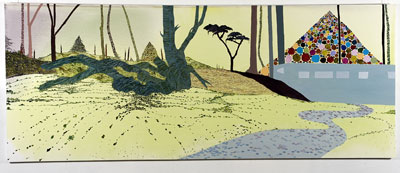

The largest painting in the show, measuring 250 cm wide, is titled O brother! Don’t climb that creepy tree. Hendrick creates a strange, Dr Seuss-like world of droopy trees, mountains comprised of brightly coloured circles and paths that seem to lead to nowhere. Again, Hendrick’s focus is on the landscape. It is as if these locations, real or imagined, have their own stories to tell. The surface of the landscape, scratched or scarred from events and passing time, becomes a surface of things remembered. Hendrick chooses sites of apparent importance, or perhaps, simply, places from her own past and childhood. In O brother! Don’t climb that creepy tree, the winding path leads me in and the landscape seems to enclose itself around me. I stand very close to the piece – the large scale of the work fills my sight. The wide, twisting tree, again, creeps over the landscape and into the sky. It is like a fairytale beanstalk growing upwards, waiting to be explored, asking to be climbed.

Roland Barthes described history as a “memory fabricated."[2] Hendrick creates a historical narrative that we wander through, piecing together, trying to make sense of it all. The empty spaces and strange architectural structures offer suggestions of narrative rather than anything concrete.

Niamh Dunphy lives and works in Dublin.