Andre Stitt is perhaps the best-known Northern Irish performance artist of his generation. It is therefore slightly confusing to note that for his first solo exhibition in Northern Ireland in seventeen years he has chosen to produce a series of paintings. To understand this decision it is worth taking some time to examine the body of work that constitutes Everybody knows this is nowhere.

On entering the gallery of the Millennium Court Arts Centre, one is met by a wall of dark canvases. So dark that one has to get close to them so they can actually be made out. As one approaches there is the faintest smell of bitumen in the air, a material that Stitt has often employed in his performance Akshuns.[1] I find myself recalling moments of intensity from his performance works, which I have witnessed, and as I do these sensations and memories go to ground in painting.

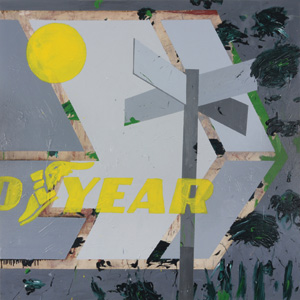

![Andre Stitt: Underpass [Drumgor West], 2008, bitumin and acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150 cm; courtesy Millennium Court Arts Centre](/wp-content/from VAC/reviews/2010/images/stitt/3.jpg)

Indeed there is something of a similarity between the aesthetic of these dark paintings and Stitt’s performance works. These paintings are gritty. Their subject matter is drawn from the urban landscape of Craigavon: underpasses beneath roads, the kinds of places youths gather to drink, graffiti and blow off steam. These kinds of places are transitional spaces and embody the tension of liminality. The paintings ooze this sensation. They feel like glimpses seen while moving through such places at speed. This sensation is confirmed to me by the title of one of the works, Leaving on a night bus.

As I move round the gallery the form of the paintings begins to change. All the works in the exhibition are abstract, but the form of the abstraction differs. In realising this I also realise that the paintings are not simply a record of Stitt’s engagement with Craigavon but also an embodiment of his dialogue with painting as an artistic medium. This is not to suggest that the body of work lacks cohesion. Rather the cohesion of the works lies in their subject matter rather than their formal composition.

The Road in (ghost junction M12) is a clear example of this. In contrast to the dark works in bitumen, this canvas is optimistically green, almost jovial. It looks like a scene from a science-fiction movie. The kind of thing one might see if approaching Craigavon from high above in the upper atmosphere. A green landscape unfolds beneath a pale grey sky, as though I am coming at it through the clouds. There are faint gray markings that could be roads or walls. In this work a terrain is defined but its content is only hinted at. I am reminded of Craigavon’s Utopian beginnings. When it was first built it was envisioned as a City of the Future, a place where industry and society could flourish far away from the madness of the Troubles, which was boiling away in the inner cities of Belfast and Derry.

Out of all the works on display, I am most struck by Dead taigs, the most figurative of all the works in the exhibition. This work is very unsettling. The central foreground of the painting is occupied by a headless lamppost; behind it we see a mess of unkept grass ascending to a horizon crowned with what look like the tops of council houses. Like many of the other works, this painting has a sense of movement in it. Yet whereas the others feel like one is travelling through the landscape, in this instance one feels as if one is standing in a landscape that is palpably decomposing. In the middle of this painting hangs a red sphere with pointed edges. It looks like a tiny sun. Its presence is uneasy, even spectral, adding to the uneasy sensation flowing from the work.

In discussing the work with Stitt, he explained how Craigavon was for him a kind of back-story on his relationship with Northern Ireland. As a teenager he had a girlfriend in Craigavon and so used to visit it regularly while it was still in its Utopian beginnings. In looking at this body of paintings and thinking about Stitt’s biography, I am not surprised that he chose painting as a medium for engaging with Craigavon. Much of Stitt’s performance work deals with issues of trauma, stemming from formative experiences growing up in Northern Ireland. Whereas performance offers one a means of embodying a subjective experience and communicating it to others through an ephemeral, intersubjective, material-based dialogue, painting offers one the means of objectifying experience and thus holding it suspended. In this way Stitt has used painting to create a distance between himself and the memories and sensations he has excavated while producing this body of work. In so doing he has created a space for both himself and others to reflect on these things in a way that could not be afforded to the viewer through a work of performance.

Justin McKeown is an artist, from Northern Ireland. This text was originally commissioned for the Spring 2010 issue of Circa Art Magazine, number 131, which did not appear.