Belfast Exposed, Belfast, 31 August – 12 October 2012

By Slavka Sverakova

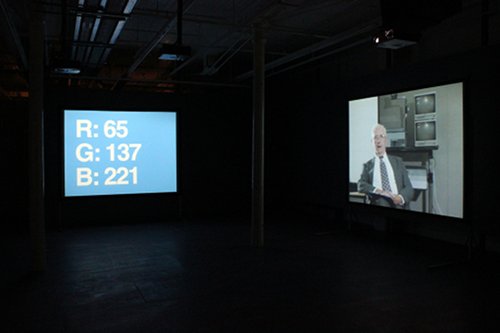

A three-screen video installation conflates several stories: Edward Hunter’s Analysis of Jane Fonda Activities in North Vietnam – a Committee report to the United States House of Representatives – Misleading information from the battlefield: the Tillman and Lynch episodes, and Gerhard Richter reading notes on political ideology. To the purposefully graded video segments Enemy Blue, Chromatic Aberration, Geisterbilder and Blue on Blue, Allan Hughes added found footage of Pat Tillman as a player for the NFL Arizona Cardinals. A part of ongoing research into the failure of video images to escape false authenticity, the installation presents both their power to define authenticity, and the easy compliance of the viewers to accept what is seen as truth. Recently (6 September), I read a comment by Michael Daley, cited in a blog by J H Dobrzynski, which echoes that concern: “What interests people today has less to do with authenticity – and more with experience of being a part of the crowd.” As an example of mass psychology, this need for sameness brings its long history to bear; however, perceived under the contemporaneous constellation of conditions, today, it threatens individual freedom in democracies as strongly as during the wars and under openly oppressive regimes.

How does Hughes portray this condition?

The installation of three screens on three walls, and a speaker above my head, became accessible from one static viewing and listening point, as if I were watching a theatre while suspending practical judgement. With the medium of theatre, the installation shared the importance of timing, speed of speech, significance of silence and a preference for a fixed position of the viewer, the (seated) audience. In most passages, my parallaxes allowed me not miss the changes, as the screens swapped images. A composition normally has two main functions, to signal the graded importance of parts, and to lead my senses along those signals (Kandinsky called them lines of visual force). The switching of narratives and images from one screen to another insisted on the equivalent importance of all segments, thus deliberately removing a hieratic relationship between the relevant sources. Moreover, the switches felt arbitrary and somewhat irritating.

The sense of negative values flooding my consciousness continued relentlessly. As long as I did not read them as deliberate, thoughtfully chosen and privileged, I felt that the installation was a failure. The words flooded the space in a torrent that substantially undermined any contemplation of the images on their own terms. Words, read or written texts, have been ubiquitous in visual-art exhibitions for decades now; as a viewer I am somewhat prepared to engage more than one sense. I have seen video art where the two, silence and sound, worked together, whereas in this case I sensed a sort of battle and over-reaction from both. The images moved from screen to screen to escape the expected short attention span of viewers, while the sound filled the space, racing to reach my consciousness first. There is no homogenous narrative to caress the images. Hughes’ intention “to explore the failure of video to articulate politicized historical narratives” (artist’s statement) has been achieved. On the one hand it is a case study of the demise of history painting as a genre, albeit lens-based. On the other, deeper level, it succeeds in creating authentic aversion, irritation, discomfort, displeasure, and disappointment. All desirable responses to propaganda as a tool to bamboozle the masses, to stop people doubting and questioning those in power; here directed at the work of art as mediator.

The voices of the three speakers dazzled with energy, conviction, self-confidence and clear hostility to anything private. No meandering thought was allowed to enter or to keep its private mystery. All was there to be devoured as a communal event. By submitting to the authority of the voices, the viewer becomes an accomplice in suspension of doubt. I recall wishing that some of Gerhard Richter’s insights were held between pauses, or repeated slowly once more, their precious magnificence lost with galloping voices. Not all words are happy to negotiate speed, air, black holes of memory. Lovers of books, we caress the words whose meaning enriches our own thinking, by resonating with them on the page, again and again. That is our living time, as opposed to the historical time related at speed in a listened-to narrative. My perception was influenced by that distinction which allowed for some significant moments to break the surface of the audio-visual stream.

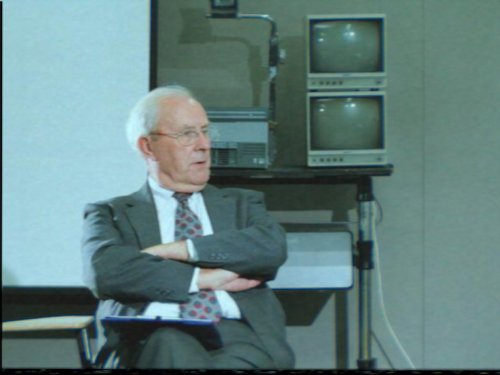

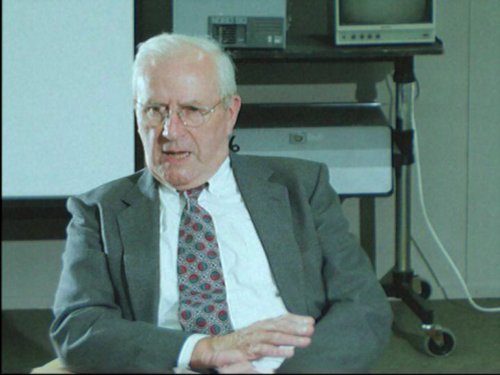

The first happened when the man delivering the analysis of duplicity of dual propaganda appeared on the screen on my left in a relaxed pose, wordlessly communicating with someone behind the camera. His acting, his superb delivery of leaving a prescribed role, introduced the warmth of a lived authentic moment. A fleeting feeling of shared space was a surprising gift. The shot was intensely private, individual. After the screen swapped him for the codes of colour, the loss of his presence was deepened by his appearing further away, again as a kind of lecturer in full swing.

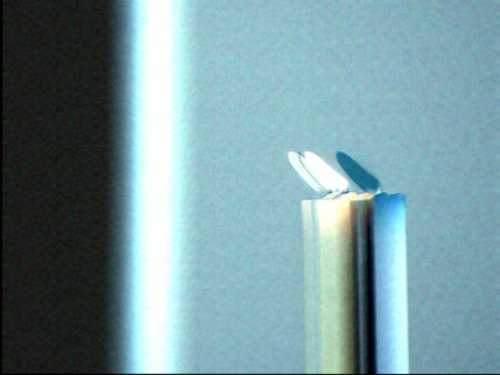

The second episode appeared as an evoked mistake, a loss of acuity to a meaning. Hughes assured me that it was not an error, when a lit-up candle shook and dissolved into parallel stripes. The change lasted seconds only, hence my insecurity about its being planned. The distressed candle, and another screen jumping slightly up and down, were both shaking off the domineering precision. Saturated by feeling, the lens blinded itself with tears and the camera copied the convulsion of a sobbing body, overwhelmed by sorrow, caused by nothing less than death.

Pat Tillman appears on the centre screen holding a protective helmet. The timing and slowed-down speed postponed closure by giving off gradual loss of life. It reminded me of a circular spiralling shot of the crowns of birches seen from below by an unseen dying soldier in Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1957 film Letyat Zhuravli (The Cranes are Flying won the Palm d’Or at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival). The image is a sobbing call to stop the war. Paul Verlaine’s Chanson d’Automne, which became a signal for D-Day to the French Resistance, wrestled into my memory, its rhythm, its Je me souviens Des jours anciens Et je pleure… These words intensified the meaning of the watched image. Evocation of feeling on its own is not an indicator of merit, nor is the ability of the work of art to touch large number of people. Nevertheless, if an audiovisual installation does not limit our ability to deeply engage with art and evokes feeling, it does more than inform, and in addition it escapes the shackles of social studies or its sources.

Hughes’s technical virtuosity allows him to break the rule of what could have been a documentary for a TV audience. I could transcend neither the dehumanizing political correctness of the left-wing positions, nor the ostentatious scholarship of the respectable man, without feeling annoyance and disgust at the loss of time for contemplation and for my individual and private questioning. The power to control a viewer thus is a simulacrum of what propaganda does to people. Successful analogy.

I confess that the meaning of ‘Enemy Blue’, the title of the whole suite, did not become any clearer after watching the work twice. Hughes explained to me later that Edward Hunter, one of his sources, invented the term. Thinking of recent reports of attacks by Afghans on coalition forces as green on blue, in the context of war, I read blue as meaning friendly. ‘Enemy Blue’ appears to be an oxymoron which, in spite of being a poetic trope, is too weak to remove the corporate tone. Assisted by what linguists call vagueness of predicates, there are two entrenched positions: vague predicates do not have referents and therefore are neither true nor false (e.g. G.Frege, 1848 – 1925) – or – they do when we drown them in contexts determined by sources. When made, the referents are those selected by the artist. When put in the public domain other referents compete for connections.

Indeed, what is in the name?

The colour blue has its own visual journal online – Cerulean. Blue is the colour of uniforms of nurses, firemen, the police, etc. It is a colour connecting us to the universe and feelings: blue planet, blue sky, blue mood, blue lagoon, blue azur, lapis lazuli…

It is a mere coincidence that the precious lapis lazuli is celebrated by two Icelandic artists, Eva Isleifsdóttir (1992) and Thorgerdur Ólafsdóttir (1985), in Monument for Blue at Catalyst Arts (6 September – 15 September 2012) not a mile away from Belfast Exposed. The artists claim that the exhibits are stages “in history that shaped the story of colour blue” (gallery printout).

Zoe Murdoch added blue to a visual metaphor for sublime mood, in a translation of Pablo Neruda’s poem Ode to Bird Watching into a photograph Ode to Blue Skies Bird Watching (2008).

The installation for Krannert Art Museum, Illinois (31 August – 30 December 2012) magnificently connects ancient craft with minimalist aesthetics. Rowland Ricketts, textile artist, and Norbert Herber, sound designer, displays dried indigo plants, indigo-dyed hemp kibira and indigo-dyed felted stones on a wall, under a tree, on the ground, savouring the calm that only the colour blue gives off.

In their various degrees of freedom works of art explore the word, the colour blue, looking for an answer in visual terms, to how colour carries the potential to alter our experience.

Hughes filled the distance between blue as a word and blue as a colour with problems with what we know and how we know it. He harnessed our senses directly to the process of transforming the images and texts into historical documents, which may be false or true. The video acts as a surface, underneath which connections can be made and unmade, cherishing individual imagination. The power of surface to hold tight to uncertainties and ambiguities has become a familiar idea in abstract painting. To translate it to lens-based media is no mean achievement. Moreover, it further undermines the expected verism of the camera.