Alison Pilkington’s background is in process-led, gestural abstract painting. Intriguingly, the works presented in her exhibition Between one Thing and Another at the Customhouse Studios Gallery, Westport (21 May – 13 June 2010) could be read as being largely concerned with contradicting the shibboleths of such a purely ‘painterly’ form of practice. On show were complex hybrid works, which fused abstract and random qualities with quasi-figurative, identical and planned elements.

The exhibition was created during the first year of the artist’s practice-based PhD at NCAD. Pilkington’s research hinges on the notion of the uncanny in relation to image – making and perception.1 Thus, all manner of explorations of mirroring, twinning and doppelgängers abounded. Untangling these picture – puzzles required contemplation of what Pilkington described as “the uncanny moment"2 – in other words, the time spent mentally juggling the experience of artworks as both ‘fictional’ representations and images, and their presence as real objects in the world.

Take for example the diptych Cut Out and Painting. On the right was a jaunty abstract collage, composed of pinned-together coloured art paper. It’s partner on the left was a painting that fused abstraction and representation – in addition to faithfully mirroring its scale and composition, it also included trompe-l’oeil renderings of the map pins used in the collage. A triptych piece, similarly titled Cut Out, added another element to the abstract / representation conundrum, namely the ambiquity between the ‘original’ and ‘copy’. Again, a key element was a collage. In this case a small-scale work made up of several layers of coloured card, through which triangular holes had been nicked on the surface, creating a pleasing multi-colour kite-like repeat pattern. Its partner was a similarly representational painting of this abstract object. The final element in the series was another painting which duplicated its neighbour, except scaled-up by about a third. This additional piece – or was it the original? – made it perplexingly unclear which of the works came first.

Besides the works encouraging a shuffling of thoughts around questions of the image, Pilkington’s arrangement of pieces within the gallery space prompted viewers to likewise mobilise their bodies and lines of sight in pursuit of constructing and deconstructing the imagery before them. One such configuration was Primitive Man / Primitive Man Reflection. It comprised a medium – sized painting partnered with a framed mirror of the same dimensions. The canvas depicted a repeat pattern of ‘primitivist’ mask-like figurative images, painted on a dark background, set within a skewed parallelogram ‘frame’. On the adjacent wall was a similar, but smaller collage comprising solely the repeat mask-like pattern

On first glance one might have paid little heed to this set up. But in pacing before this work and scanning the surrounding gallery space, something odd became apparent. Suddenly, the painting had a partner. The image on the adjacent wall – Primitive Man Collage – appears in the mirror. Rather unsettlingly, it became clear that the painting next to the mirror was actually a representation of what now was reflected in the mirror. Thus, at the right viewing angle two identical images became visible. One was a painted representation, the other a ‘real’ image – albeit existing only on the illusory space of the surface plane of a mirror.

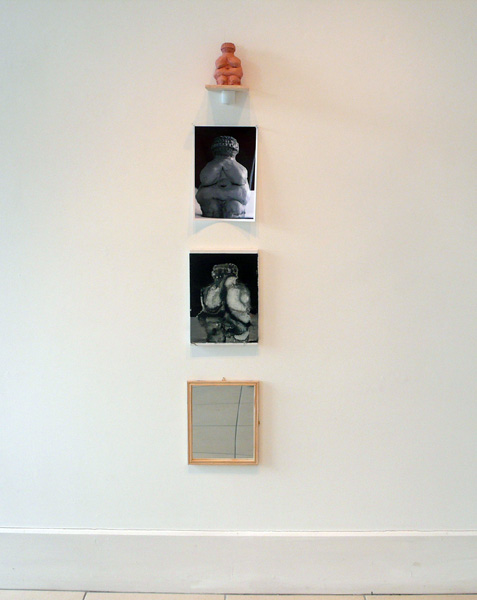

A further play on notions of the ‘past’ and ‘present-ness’ of the image occurred in the work My Willendorf. Mounted at head height was a small clay replica of the famous primitive sculpture the Willendorf Venus.3 Below this was hung a photograph of this object; and underneath was a painting of the sculpture. The final element was a framed mirror of the same dimensions as the two images above it, situated just above the gallery skirting board. Viewers were again presented with a puzzle as to the provenance of the images. Which begat which? Was the painting of the object or the photograph? Was the photograph an image of Pilkington’s sculptural replica of the Willendorf Venus; or a copy of an original archival image of the ‘real’ Willendorf Venus?

As intriguing as this puzzle was, perhaps the real key to this work was its non-representational element. The mirror at the base of this series of images prompted curious viewers to crouch down to be confronted with the most fascinating and uncanny of all images to most us – our own reflection. Indeed My Willendorf highlighted the really quite strange relationships that exist between objects, images and the world. For example, a fetish object like the Willendorf Venus, for its creators and users, was perhaps as much a ‘personage’ as being symbolic and representative or ‘thing’. This rather primal relationship to representations of other humans has never gone away – whether we are viewing images from our family albums or celebrity gossip photo-magazines – we are hard-wired to seek out and identify with resemblances to our own kind in the world around us.

This type of anthropomorphic and psychological complexity of the images and objects was of course also explored by early-modernist artists – particularly of a surrealist bent – via their interest in primitive art, dream imagery and the subconscious. Pilkington paid explicit homage to these pioneers – Hans Arp and Yves Tanguy were name-checked by the artist in the press release. But likewise, Pilkington’s interest in exploring the ‘objecthood’ of the image and use of game-playing tactics can be seen to be equally indebted to the self-reflexive practices of the conceptual and minimal artists of the 1960s and 1970s.4 As well as this, more contemporary touchstones for this exhibition would include the philospher Jacques Rancière’s calls for the centrality of the art viewer; and the recognition and deployment of the political potential of aesthetics.5

Pilkington’s achievement in Between One Thing and Another was to successfully reconfigure a diverse set of strategies and concerns, in order to offer a very timely critique and perhaps even antidote to contemporary visual culture. In their playful complexity – combined with an encouragement and acknowledgment of the viewer’s participation in image-making – the works in this exhibition added up to a robust rebuttal and alternative to the superficiality, virtuality and authoritarian nature of the images that saturate the contemporary media-scape.

Jason Oakley is Publications Manager, Visual Artists Ireland, and Lecturer in Contextual Studies, IADT Dún Laoghaire.