Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth, Oscar Wilde sagely observed two centuries ago. Alias, at the Photomonth Festival in Krackow this year, does not refer to Wilde specifically, but his dictum hovers behind one of the most intriguing and imaginative shows I’ve seen in quite a while. Acting as curators for the first time, London-based photographers Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin pursued the theme in a novel way by creating a multi-layered exhibition that fell into two main sections. One was a historical survey of fifty-five artists using a heteronym. The latter term, devised by one of the literary sources for the exhibition Portuguese poet Ferando Pessoa, describes a fictional persona with an established biography inhabited by the artist. Pessoa used over seventy names when composing different kinds of poetry. Roberto Bolano’s Nazi Literature in the Americas, an anthology of fictional authors, was another source. Both inspired the curators to open up a debate about the idea of the artist as a brand-name in a market-dominated world, as well as aspects of authorship developed by Roland Barthes in the late 1960s. The exhibition also focused on the fiction and reality of photography itself. Broomberg and Chanarin’s own recent projects in Belfast, People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground (2011) and The Day that Nobody Died (2008) in Afghanistan, addressed both issues, using images altered by other people in the former and random sunlight in the composition of the latter.

The other section of the exhibition presented an inventive way to look at authorship and reception. Commissioned artists and writers were brought together to create fictional artists who then produced an artwork. As the author / artist in each case remained anonymous both were free to create, at least theoretically, in ways that departed from their usual practice. But this also presented a challenge to the audience’s judgment of the artworks deprived of any prior knowledge of the artist’s work. While the pairings of author / artist remained unknown, they were listed individually in the catalogue. Some of the artists were Gabriel Orozco, David Goldblatt, Alec Soth, Brown & Bri,and Broomberg and Chanarin themselves; some of the writers were Jennifer Higgie (Bedlam [2006], co-editor Frieze, The Artist’s Joke [ed.][2007]), Ekow Eshun (writer and broadcaster), John Haskell (I Am Not Jackson Pollock [2003]), and Alexander García Düttman (Philosophy of Exaggeration [2004]). Joseph Cornell (b. 1930), Gerald D’Amato (b. 1946) and Dora Fobert (b. 1925) were some of the fictional artists created. Fobert was a Jewish photographer who took clandestine nude photographs of young girls in the Warsaw Ghetto which, the accompanying story tells us, now exist only as unstable paper negatives as she could not get fixer or negatives. The beautiful ghostly black-and-white images shown, however, were shot in London and perfectly stable, we learn from an interview with Broomberg and Chanarin. Each artwork in this section was presented with a fictional wall caption and text panel, drawing attention to the fact that both are habitually looked at before the actual work. The twenty-three commissioned works and texts were distributed in different venues throughout Krackow, creating a kind of mystery trail that augmented that of who was artist and who was writer.

The historical survey in the Bunkier Sztuki gallery opened with the “major artistic touchstone” of the exhibition, Patrick Ireland. This was the alias taken in 1972 by the New York-based Irish artist Brian O’Doherty as a protest against the Bloody Sunday killings of civil rights marchers the same year in Northern Ireland. It was an artist name he held for thirty-six years until the conditions he had vowed to live by were finally fulfilled: the restoration of civil rights and the withdrawal of the British army. The main exhibition poster as well as the catalogue cover featured a photograph of O’Doherty looking into the coffin of Patrick Ireland in May 2008 before he was buried in the grounds of the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin. Documentation of the original Name Change performance and a photograph of the tombstone were shown with a 1990s video of the critic Brian O’Doherty commenting on the work of the installation artist Patrick Ireland. O’Doherty as a writer and critic also successfully maintained other heteronyms – Mary Josephson, William Maginn and Sigmund Bode – for a similar period, only revealing their ‘true’ identities in 2002. In the light of Alias’ theme, it is interesting to note that it was O’Doherty who first commissioned Barthes’ famous essay, ‘The Death of the Author’ for Aspen 5+6, a magazine / exhibition in a box in 1967.

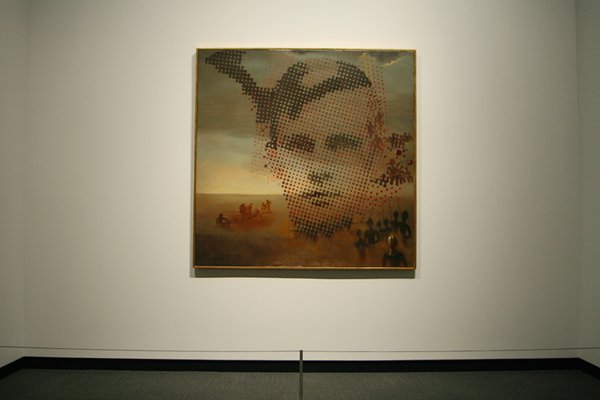

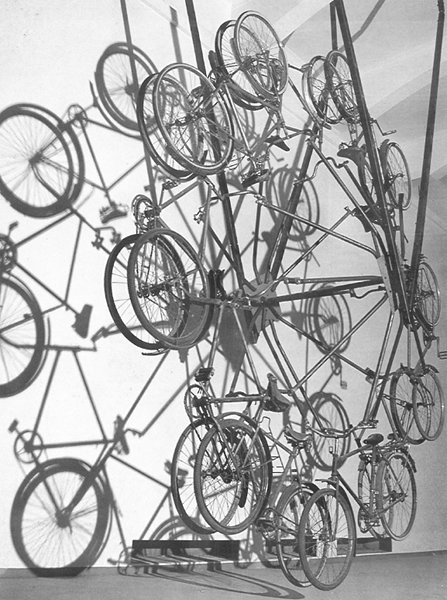

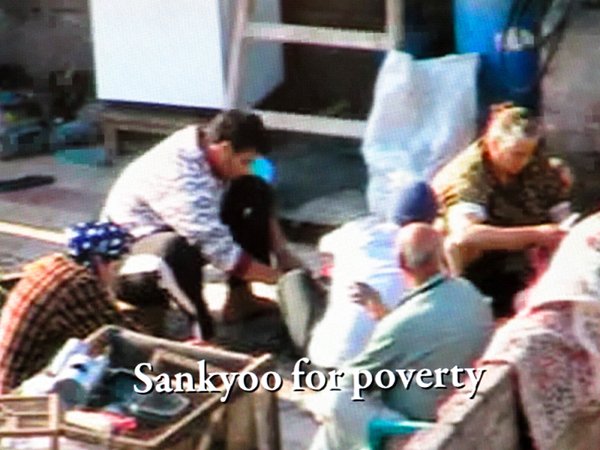

Moving from this first room one encountered Salvador Dalí, who believed he was the reincarnation of his dead brother, also named Salvador; Rrose Sélavy, invented in the early 1920s by Marcel Duchamp; John Dogg the artist (b. 1986), revealed as a fiction at Richard Prince’s retrospective in the Guggenheim in 2007; and the artist known only as Balthus (the Polish-French artist, Balthasar Klossowski de Rola [1908 – 2001]), who suggested the caption “Balthus is a painter of whom nothing is known. Now let us look at the pictures,” for his 1968 Tate retrospective. Besides such big names as the above there were groups such as the Atlas Group (the creation of New York artist Walid Raad), and the exhibition Constructed Art History shown in Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts in 1988; the six exhibited artists were all inventions of artist / curator Peter Weibel, who also wrote six fictional critical essays in the catalogue. Departing from the artistic frame of the exhibition, the curators also included the serial child-impersonator Frédéric Bourdin (b. 1974), who claimed to have assumed over thirty identities including that of the American schoolboy Nicholas Barclay, convincing his family for three months that he was their long lost son (Fig). The topical nature of the exhibition was brought home by a video To President Mubarak: Sankyoo (2007) about poverty and the abuse of power in Egypt by Ahmad Sherif. Days before the exhibition opened the artist and musician Aalam Wassef revealed that for years prior to the Spring Revolution he had created work under various pseudonyms, including Ahmad Sherif, who became a pivotal figure in the social media that spearheaded the revolution.

A few reservations must be included here. In spite of the premise of the exhibition, some heteronyms seemed better described as pseudonyms. Claes Oldenburg, for example, only used the alias ‘Ray Gun’ for a number of projects, while Oldenburg is the artistic persona known internationally. Similarly Rauschenburg and Johns appear to have worked as window dressers under the name ‘Matson Jones’ for a period in the mid-1950s, before becoming the successful artists we now know. In other words, in neither case does an alternative biography appear to have been created. Others in the exhibition however, like Patrick Ireland for example, lived and worked for decades while many were unaware that he was an invention of O’Doherty’s. This was illustrated by the two completely different entries for O’Doherty and Ireland in Who’s Who in America one year.

This eclectic fascinating show is one that should travel not least because it demonstrates how non conformist statements can be made about art and issues that affect a large number of people but also for the challenge it offers to curatorial and viewing practices.