Louise Neiland’s 366 moons is a series of evocative and reflective paintings recently on show at The Lab. Dublin-based Neiland engages with ideas surrounding the nature of time and our relationship to it. Time, being undefinable, does not play by our rules. In Neiland’s efforts to understand the measurement of time, she looks to something in nature that is tangible, unchanging. She looks to something we can compare our own limited and imperfect measurements of time with – the moon.[1] The work was started in 2008 – a leap year. A leap year is a year where an extra day is inserted into the year to keep the calendar year synchronized with the seasonal and astronomical year.[2] As a result, the year contains 366 days.

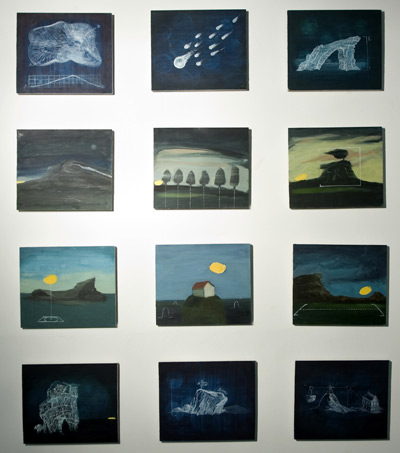

Stepping into the gallery, it is quiet and still, apart from the slow and steady tick of a metronome keeping time. A small group of paintings hang, grid-like, near the entrance. A year of a day is a series of oil paintings on board that examine the passing of time through still images. Neiland acts like an engineer, surveying the landscape, using scales to weigh and measure. Some of the paintings resemble contour drawings or topographic maps – studying the landscape, perhaps tracking physical changes over time. The white lines against the dark blues seem ghostly, skeletal. Colours are soft and muted. Earthy browns, sombre grays and a palette of blues are accented with flashes of yellow and soft beiges. The contrasting light and dark remind me of nineteenth-century German Romantic landscape painting: the contemplative, solitary figure silhouetted against night skies, misty hills, barren trees or Gothic ruins. [3] Yet, Neiland’s work is devoid of people. Only a small, isolated house and tools of measurement are traces of any human interaction. Perhaps we, the viewer, are that solitary figure contemplating the expansive landscape and trying to make sense of ourselves within it – a mere tick on the immutable clock of time.

Moving along the exhibition, there are two paintings. Origin, a small oil painting on board, is placed near the ground, close to the corner. There is a small campfire burning. Adjacent, is a large-scale painting of a forest fire entitled Brisbane ’08. A brightly burning fire destroys a forest and dark smoke billows into the night sky. The large painting is so vivid and grand in scale that you almost miss the small painting beside it. Neiland seems to tell a story, or alternatively, records a history as each image leads into the next. The title of the small painting indicates a beginning of something – maybe this is how the fire began. Neiland only leaves clues for us to piece together. Following these two paintings is another small painting on board titled Still. This painting depicts the result of the fire, the aftermath. Trees are burned and there is calm. There is also feeling of melancholy to the work, in that something has ended or been destroyed,- the energy and destruction of the fire has ceased. Within these three works, there is a linear progression – each work is connected to the other. Perhaps it is the same place but at a different moment in time. Neiland presents the viewer with a beginning and an end. In the background, the sound of a measured and mechanical beat goes on. We are reminded that life continues – time rolls on.

At the centre of the room, two large-scale oil paintings on paper face each other. Firstly, 366 moons shows a low, green and lush landscape painted beneath an enormous sky of moons. The earth seems small beneath the calm blue and rusty red sky. Each moon is different. Attention is paid to each crevice and surface detail. Some moons are bright and vivid, while others are translucent and ghostly – more like stains in the sky rather than solid objects. One moon, hovering closer to the landscape than the others, is connected to the surface of the earth by a dotted white line. I imagine the moon is lassoed to the earth, unable to move. Facing 366 moons is another large-scale work, 11 moons. In order to match solar time, back in 1752 we had to adapt the recording of time to nature’s rhythm. A system was introduced which replaced the so-called ‘flawed calendar’ (the Julian calendar) with one that allowed us to be in sync with the solar calendar (the Gregorian calendar). To do this, 11 days were removed from the calendar year – 2 to 13 September, 1752; it was as if these days never existed. Some people became angry over these ‘missing days’ and felt that days had been removed from their lives.[4] In the painting, it is evening. The gray-blues darken the landscape. A small house at the side of the work is brightly lit from within. The soft, yellow hue escaping the window and the door are strange against the dark, blue night. This work, more than any of the others, shows a human presence – a house, and calculations to measure and record are drawn out again in white lines. The landscape is smaller and the sky doesn’t seem quite as endless.

Centreville ‘56 is the largest painting on paper in the exhibition, measuring 495 cm high. There is a house sitting within a calm landscape; a comet or moon or some bright yellow object speedily shoots towards it. This moment before the collision, between falling object and earth, is halted. A second is captured and made still, like a snapshot. There is movement in the brushstrokes and bright, lively colours – the work is full of energy and speed. Looking at the work, which reaches the ceiling, makes me feel very small as I look upwards into the sky. If Neiland was to paint the following second – the house would be destroyed, the landscape red instead of green. I am reminded of the frailty of life, the inevitability of an end – an eventual end to my existence anyway. Tick.

Next to Centreville ‘56, there is a simple and effective installation entitled Cadence. The word ‘cadence’ in music theory literally means ‘falling’ and indicates the end of a phrase, or conclusion to a section of music.[5] A video of a falling object, resembling a moon, is projected on the wall. It falls quickly and disappears. A moment later, another falls, disappears. Beside it, placed on the ground, a metronome slowly and meticulously counts time. Here, Neiland presents two rates of time -the incessant ticking of the metronome juxtaposed with the random, free fall of the object. Sometimes they appear to be in sync, sometimes one appears to be chasing the other. The video projection steps in and out of the metronome’s steady beat. There is a sense that time cannot be controlled – is constantly changing and moving forward. Neiland plays with time, overlapping moments, speeding up and slowing down. There is repetition in the work; different ways of looking and trying to understand time are investigated.

Neiland’s engaging body of work, relating to her understanding of time, has led to a series of impressive and thought-provoking images. The large-scale paintings on paper showed an understanding of both colour and texture. The task Neiland has undertaken to represent time through still images is a difficult one, yet her work seems to achieve this in a subtle and effective way.

Niamh Dunphy is a Dublin-based artist, currently interning for Circa.