|

| Post-performance interior view of room 2; photo / courtesy the author |

There was a palpable sense of anticipation before 18 happenings in 6 parts by Allan Kaprow, part of Performa 2007, the second biennial of visual-art performance in New York; an air of excitement as the audience waited to be admitted to the purpose-built re-creation of the original space of the Reuben Gallery where 18/6 was first performed in New York in 1959. We, the audience, were being given the chance to experience a seminal event in the trajectory of contemporary art. The happenings were presented in three rooms separated by walls made of transparent plastic sheeting. Each part of the happening was clearly defined with the sound of a loud gong. Intervals of either two or fifteen minutes punctuated the parts and the audience was asked to change seating according to instructions given to each audience member as they entered the space. Sitting there waiting one felt, as Kaprow had desired, ‘Here is something important’.

|

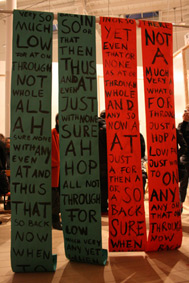

| Installation detail; photo / courtesy the author |

But it was important in a different way to the original performing of 18 happenings in 6 parts . The original was heralding a change in the way that art was made and conceived of. It called for a ‘total art’, something “utiliz[ing] the specific substances of sight, sound, movement, people, odors, touch." [1] The reenactment was significant in our ability to experience something that has past, to turn back time, to grasp the ungraspable, like a clairvoyant who lets us speak to the dead. But 18 happenings in 6 parts remained ungraspable, as one can never completely experience the whole. With simultaneous actions taking place in each of the three spaces, the viewer was only ever be able to experience a part.

In witnessing the event, one could not help but feel that the work was familiar – not only because of the documentation of the original but also due to our experience of contemporary art practice. The work did not have the same shock or surprise as one would have imagined it to have in 1959. We are encouraged to see beauty in the most mundane actions – squeezing an orange or bouncing a ball – but this has become natural to us now. The montage of staccato electronic sounds, choreographed everyday movements of the body and minimal nonlinear language read like a contemporary avant-garde theatre piece in the vein of Richard Foreman. As a viewer who is habituated to these forms, it is impossible to experience this performance in the same way as the original.

|

| Chelsea Adewunmi, Noémie Solomon, Sebastian Calderón-Bentin and Kyle Shepard Performing in 18 Happenings in 6 Parts; photo / courtesy the author |

Happenings take place in time and space. Consequently the context also has a bearing on our reception of the work. While the original directors of the previous re-enactment in Haus der Kunst, Munich, were at pains to create a situation that would be both true to the original while also positioning it within a museum context, the creation in Haus der Kunst of the original gallery structure in the larger white-cube space seemed at odds with the original intent for the work. It seemed to monumentalise the work and the event, removing it from the everyday experience that Kaprow strove for. The recreation of this structure in the Deitch Studio for Performa has a similar effect.

This is not the first time that Performa have chosen to present reenactments of past performances. In 7 easy pieces, Marina Abramovic reenacted the performances of Joseph Beuys, Gina Pain, Valie Export, Vito Acconi, Bruce Nauman and one of her own earlier performances as part of Performa 2005. [2] Writing about this work Jennifer Blessing points out that the recreation of a work invites comparisons with the original. [3] As was also seen in Abramovic’s re-enactments, it is impossible to re-create the original. Perhaps therefore it is more apt to speak of a re-invention of 18 happenings in 6 parts, as was proposed for the re-creation of Kaprow’s environments in 7 environments in Fondazione Mudima, Milan, in 1991. Rather than looking to what has been, it is proposed that “the reinvention of pieces injects fresh life into them." [4] The reinvention of 18/6 then gives the contemporary viewer the opportunity to experience this work in a completely new way, to see it as something different from its previous incarnation.

|

| Pre-performance interior view or room 3.; photo / courtesy the author |

Thus in witnessing this reinvention of Kaprow’s work we must ask ourselves: What does it mean to make this work now in 2007? Is the work still relevant? How do we respond to the work as contemporary consumers of art? Kaprow wrote of a need for a sense of crisis in the creation of art. “The real weakness of much vanguard art since 1951 is its complacent assumption that art exists and can be recognised and practiced." [5] Perhaps Performa sees a similar crisis in a city where the art world is still very much commercially driven. As Roselee Goldberg, the curator of Performa, wrote, “For the very act of creating performance, of producing ephemeral work in an art world of objects and collectibles, unsettles assumptions about the very nature of art." [6] Kaprow’s happenings call for a revolution in the way we make art, and perhaps the reinvention of this work calls on the viewer to consider the state of contemporary art today and how far we have come to creating a total art.

Michelle Browne is an artist based in Dublin.

1 Kaprow, A. ‘The legacy of Jackson Pollock’, in Essays on the blurring of art and life, ed. Jeff Kelley, 2003, Berkley and Los Angeles, University of California Press

2 See review in Circa 115, spring 2006.

3 Blessing, J. ‘7 easy pieces’, in Goldberg, R., Performa new visual art performance, 2007, New York, Performa

4 Restany, Pierre, ‘Reinventing and re-membering’, in 7 environments, Kaprow, A., 1992, Rome, Mudima &Studio Moria

5 Kaprow, A., ‘Happenings in the New York scene’, in Essays on the blurring of art and life, ed. Jeff Kelley, 2003, Berkley and Los Angeles, University of California Press

6 Goldberg, R., ‘The shock of the live’, Art Review, Vol. 58, November 2005